Gastromondiale comprise a diverse group of diners and critics who believe that gastronomy ought to be directed foremost to the unadulterated pleasure of eating and drinking. In contrast, today’s restaurant industry capitalizes on dishes that dazzle the eye but leave the palate numb; articulate complex ideas that translate poorly to the plate; advance a high-minded political agenda but abandon the quotidian duty to render the utmost to the diner who comes to the table.

The hedonist stance of Gastromondiale is therefore less reactionary than resistant to the expedient aims of the market and its ideology. In this distrust of the marketplace of ideas, our stance has more than a single affinity with the popularizer of madeleines (for which he exhibited no outspoken affinity), Marcel Proust. In contrast to the naturalist authors of his epoch, Proust was skeptical that a literature which took recourse exclusively to sociology or biography, easy sensationalist tag lines, could access a truth that palpably insisted itself into one’s very being. The way Proust assessed the literature of ideas is akin to how we view the gastronomy of ideas: mildly interesting but hardly compelling. Proust sensed that the Intellect was important, indeed integral, but only when it is preceded by the physical sensation that disturbs us out of our complacency, forcing us to think.

At Gastromondiale, we are moved by dishes that entice our senses and only subsequently instigate us to consider the technical or semiotic dimensions of a dish. The organoleptic aspects may provoke comparisons. One tastes the rey fish at Güeyu Mar and the variegated textures also encountered in wagyu are superseded by a depth of flavor more profound than any beef. The historical relevance of a dish can equally follow suit. Alain Passard’s vegetable pasta transports the diner to an alternate history of Roma, where the spaghetti carbonara might have benefited from the minerality of potatoes. Suffice it to say, both dishes send one uncontrollably on a path of rumination. In their initial, visceral appeal, they resemble madeleines. It is in this spirit that we appropriate the Proustian icon to denote three privileged moments from the dining year 2018.

Vedat MILOR

Becada (Woodcock) a la Prensa at Horcher (Madrid, Spain)

In a year that featured some amazing becada preparations at Ca L’Enric and Al Kostat in Catalonia and Apicius under chef Vigato in Paris, this classic preparation in what may as well be one of the last surviving representatives of the early 20th century European “haute cuisine” came on top. The press they use to squeeze the carcass is not for show; it adds depth to the amazing rich sauce with jus, port and becada liver. I do not know how long the “faisandage” is; all I know is that they know how to maximize the minerally taste without sacrificing juiciness.

Cigalas (Langoustines) at D’Berto (Pontevedra, Spain)

I love these crustaceans, but more often than not I end up being disappointed with them even in the best restaurants. This was not the case in D’Berto. Sweet, succulent and elegant yet firm texture, they possessed all of the qualities for which I have been looking. They were cooked a la plancha. The homemade potato chips were quite amazing too.

Ile Flottante a la Truffe Blanche d’Alba, Emulsion aux Cèpes at L’Ambroisie (Paris, France)

The pico magnatum-egg combination is always a perfect marriage, but this one exceeded all expectations. Until I have had Pacaud’s version, my favorite was “uovo in cocotte al tartufo bianco d’Alba” with rascera cheese at Da Renzo in Cervere, Piemonte. But Pacaud’s version was beyond ‘unbelievable. It was transcendental!

Besim HATINOGLU

The tension between the traditional and the modern is a recurring theme in gastronomy, with the emergence of avant-garde movements at different periods of France’s history exemplifying this well. In the 18th century, authors such as La Chapelle and Menon distinguished their approach from traditional cuisine and labelled it nouvelle cuisine. The cooking of Marie-Antoine Carême in the early 19th-century and Auguste Escoffier in the early 20th-century later inspired another nouvelle cuisine movement in the last century. Chefs trained by Fernand Point such as Paul Bocuse and Jean and Pierre Troisgros were pioneers of this movement, which was brought to public attention by food critics such as Henri Gault, Christian Millau and Andrè Gayot. While all ‘nouvelle’ movements typically share one common trait—to break with tradition—they may differ in terms of how they go about it.

Particularly beginning with Ferran Adrià, the emphasis in fine dining has been on extra-taste factors ranging from entertainment and surprises to story-telling and the commodifying of certain ideals. As a result, the constant pursuit of innovation combined with the art of plating have now become the super-values for the most popular of today’s chefs. The absolute reliance on these super-values, and the loss of balance between them and the tastiness of dishes often come at the expense of gustatory pleasure. Try to talk to someone who ardently defends the dishes of an innovative chef such as Mugaritz’s, Andoni Luis Aduriz. Most of them will disregard your concerns about the tastiness of dishes and argue that this is not the intention behind them. In their minds, there are cerebral dishes similar to films which continue to resonate after you finish them, and deepen over time. This is the false promise of avant-garde cuisine. So-called cerebral dishes—or concept dishes—lose their essence once they are ‘seen’ and ‘eaten’. Generally, any mental stimulation the dish provides is also momentary. Tastiness/gustatory pleasure is the only real element that would provide a dish with a sense of continuity. It would affect you such that you would start to plan your next visit, and you would count the days until that visit.

Adria’s avant-garde ‘tradition’, with its increasing emphasis on innovation has had far-reaching consequences for gastronomy in general and for the cooking profession in particular. One adverse effect is the inability of chefs to develop in-depth knowledge or practice in specific areas and the imposition of incomplete and underdeveloped dishes on the diners. In a sense, this is the equivalent to the renunciation of the significance of mastery. Here, then are my madeleines from 2018, each of which is in praise of mastery.

Kiymali Pide at Tadal Pide Salonu (Istanbul, Turkey)

Pide is similar to a flatbread “pizza” with cheese or meat toppings. It is made in most regions in Turkey, but some of its best examples are from the Black Sea Region. The style of pide may vary greatly across the region according to the type of dough, its thickness, or the ingredients used as toppings. Tadal Pide Salonu is not located in the Black Sea Region, but its pide master-owner, Murat Usta, adopts his hometown’s style from the east of Trabzon. Murat Usta’s father was a bread maker and started to make pide later in life. Murat Usta spent the first six years of his apprenticeship watching his father controlling the fire in the stone oven that his father built by himself. I particularly enjoy Murat Usta’s closed dough pide with a ground beef filling prepared with some onion, black pepper and salt. He cuts the top off of his kıymalı pide and adds some top-quality butter from Trabzon. I often find myself dreaming about pairing this pide with Lambrusco, but unfortunately the restaurant does not have an alcohol licence.

What makes this place so special? I am particularly fascinated by the nuance between how simple food looks and how complex the process behind them is at such places. You will be able to appreciate it only when you try the best examples of pide. Murat Usta’s pide reflects 20 years of mastery with an extremely crisp dough. He is making pide seven days a week and he only closes the restaurant during the month of Ramadan. Think about working in front of a fire every single day, making the same dish over and over again. He uses no recipes and simply extends his arm outside of his restaurant to feel the temperature in order to tell how he should prepare the dough.

To most of us, Murat Usta’s job may feel like a Sisyphean task. Leaving that aside, there is a purpose to the repetition of the work, for this is what true mastery is: producing pide at such a level at a very affordable price, a task that is otherwise unattainable. However, this takes me to another issue: Are mastery and creativity mutually exclusive concepts? They are not, as my next dish’s inventor exemplifies.

Margherita Sbagliata at Pepe in Grani (Caiazzo, Italy)

Comparing a particular dish with its top counterparts is vital for gastronomic assessments. As I have not had a chance to try some of the benchmark pizzas, I cannot claim that I am an expert on pizza. But you do not have to be one to understand how talented Franco Pepe is as a pizzaiolo. There is a story here similar to that of Tadal Pide: Franco inherited his vast know-how from his father. In fact, it all started with Franco’s grandfather who was a bread maker who started to make pizza for his friends. His pizzas became popular, and he began to make pizza for the public in 1961.

Franco mastered the craft, but at the same time he differed from his pizza-making brothers with his desire to develop new ways of making it. Due to their differences, Franco left his brothers to open Pepe in Grani in 2012. He keeps saying that he is only a simple pizza master, but obviously his initiatives make him more than that. First, he only uses products from Caiazzo and nearby villages. He works very closely with producers of his ingredients to make sure that he gets exactly what he needs. Second, Franco takes his pizza dough to another level: touching it feels like holding a cloud. Third, similar to Murat Usta, Franco is led by his experience and instincts. He says that “there is no perfect recipe for pizza”. Any recipe would change according to water hardness, humidity, and temperature. Finally, Franco bridges tradition and innovation. His ‘Margherita sbagliata’ is the product of his attempts to improve on a 30-year-old family recipe and literally means “Margherita made wrong”. Instead of using a tomato base, he tops the dough with mozzarella from Caseificio Il Casolare before it goes into the oven. After the pizza is baked, he squeezes stripes of raw tomato (pomodoro riccio from Caiazzo) and basil purees across the top.

Pepe’s ‘Margherita sbagliata’ is innovative in two senses. It has an interesting story-telling element. It demolishes the traditional roles in a Margherita by magnifying the flavours of pomodoro riccio over the mozzarella. Yet it is also more traditional in the sense that all of the ingredients become purer and more precise on the palate. Franco achieves this by shifting the places of the mozzarella and the tomato and by adding raw tomato with Caiazzano oil and basil after the dough with the mozzarella base is baked. This prevents the pizza from getting soggy.

Creativity and mastery are obviously not mutually exclusive concepts. However, most chefs rely on creativity and constant changes without actually grounding themselves in comprehensive knowledge or experience. Franco Pepe’s case exemplifies very well that creativity in the right hands can achieve unique results, but only when the foundation of a dish is tastiness.

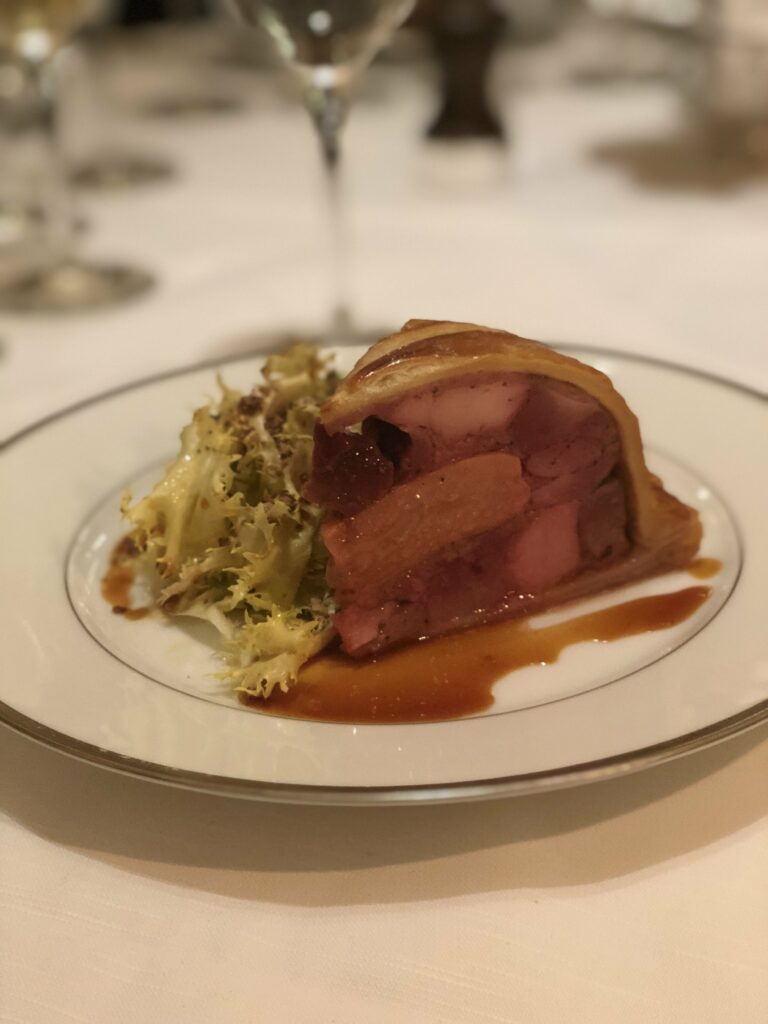

Tourte de canard aux foie gras at L’Ambroisie (Paris, France)

Chef Bernard Pacaud’s ‘tourte de canard aux foie gras’ is an off-menu classic that you have to order in advance during late Fall. It consists of pieces of duck breast, duck thigh, filet of veal, and buttery duck liver stuffed inside a puff pastry. It goes without saying that Pacaud only works with the best ingredients, and all of these ingredients work harmoniously. To my mind, this is similar to Hegel’s concept of aufhebung which has a dual meaning: to preserve and to cause to cease at the same time. A thing “is removed from its immediacy and so from an existence which is open to external influences, in order to preserve it. Thus what is sublated is at the same time preserved; it has only lost its immediacy but is not on that account annihilated”*. As Vedat Milor stated, ingredients, flavours, and the balance of the main components are all exceptional. But he says something else which, I think, showcases the culmination of decades of culinary mastery: “I would not have understood the historical significance of this dish had Atahan Tuzel not brought to my attention its decline during the sad period when the son Matthieu was running the kitchen. […] It is quite incredible how “airy” and well-cooked the thin dough is without being soggy. Pacaud minimizes the thicker part to achieve absolute harmony and the best cooking of the meat and foie gras. During his son’s reign this proportion had changed in favor of the relief (the thicker part of the dough, which helps to cook it), which made cooking easier but made the duck over-cooked.” What I also find fascinating about Matthieu’s failure with the tourte de canard is that it reveals what Pacaud has in common with masters of very non-formal, traditional delicacies. Someone who truly masters a craft develops better instincts; has superior ad hoc judgments when things go wrong. He observes and responds according to his instincts in the best possible way.

I cannot think of a better example than this to illustrate true mastery. The dish is what is called a plat d’anthologie: A dish that Pacaud has been making since the late 70s when he was an apprentice at Claude Peyrot’s restaurant Le Vivarois. This takes me back to the point that I made about ‘new tradition’ in which the younger generation of chefs embark upon a constant search for inventions and novelties. Chef Aduriz is a chef who approaches the challenges in his kitchen from a scientific perspective and attempts to expand the boundaries of gastronomy through innovation. But Pacaud’s approach is as scientific as Aduriz’s approach. Science is not always the constant exploration of different areas. Once a substantial finding is made, it is usually necessary to focus on that area and deepen one’s knowledge. In fact, I do not think that we need to justify Pacaud’s cuisine as a different form of scientific approach. The real attraction about tourte de canard is that it is a dish that is hardly served anywhere else… Or, even if it is, you simply cannot attain the same level as Pacaud’s.

The tension between the traditional and the modern; the undeserving praise for underdeveloped dishes for the sake of novelty; and more precisely, the madeleines that I have chosen remind me of what Hannah Arendt said: “The most radical revolutionary will become a conservative the day after the revolution”. How apt when we think about Pacaud, one of the members of the nouvelle cuisine movement at the time. If the revolutionary aspect of your approach is so temporary, what is truly left of your dishes?

* The Hegel Reader by Stephen Houlgate, 1998

Robert BROWN

With my gastronomic motto being “Forward with the arrière-garde”, my three foreign excursions avoided tasting menus (unless you count omakase and kaiseki), chemicals, sous-vide and (let’s not forget) sliceydiceydribbydrabbyitsybitsy. Paris and Piemonte were the sources of my three Madeleines, but why not Japan, you ask. Like multitude of bloggers and peripatetic foodies, I enjoy immensely eating in Japan. Like France and Italy were in the late 20th-century, you have to do slipshod research to stumble into a bad meal. But with gaining my gastronomic chops in France in the last third or so of the 20th-century, I prefer dishes that linger and you lose yourself in, which is not to say I enjoy a great address for sushi less than most other people. Then nine days in Sicily resulted in pretty good consistency with the exception of a few mediocre dinners. One dish that gets honorable mention is a “soup” of mussels, not a soup in our sense of the word, but not much more than a coating of tomato and garlic sauce beneath the juiciest, freshest mussels I can remember—this at Trattoria Caico in Agrigento. We followed on with four nights in Paris, and while L’Ambroisie was one of my Madeleines, there were some honorable mentions from Alain Passard whom we have been patronizing since 1986, his first year in business. His chestnut soup and carpaccio of St. Jacques were indicative of his not missing a beat after all these years. Le Tajine in the 9th arrondissement yielded one of the best couscous and tajines we have ever had, which is saying quite a lot. Sweet things are not Madeleine -eligible, but we can’t get enough of Fergus Henderson’s donuts at the St. John bakery in Neal’s Yard that are so light and not cloying.

If you just bop over on this site to my article on L’Ambroisie’s Bernard Pacaud, you will find Madeleine #1, Escalopine de bar à l’émincé d’artichaut, nage, réduite au caviar golden a.k.a. Escalope of bar (sea bass) on a bed of sliced artichokes, poached in a seafood reduction with golden caviar. I don’t know where Bernard Pacaud finds his fish, but his fishmonger ought to get some culinary award or be made an honorary member of Le Club des Cent. The escalope was so silken, springy, and tender that the memory of it will haunt your reverie.

Madeleines #2 and #3 we met up with on a late truffle-season jaunt in Piemonte. For the second straight year, I turn to Antica Corona Reale (da Renzo) for a dish I will never forget. Chopped raw veal is what you’ll see on nearly every menu in Piemonte, but I would bet my bottom Euro that you won’t find one as flavorful and silken as the one at Antica Corona. Now I’m likely in the minority of ardent fressers who don’t feel a compulsion to photograph every dish they eat, which happened to include this minor miracle. Nor did the people at Renzo, as all they could provide me is a picture of what they call “Cervere-Parigi”, “Cervere” being where the restaurant is and “Parigi” being the Italian name for Paris, given that the dish of that name is made with black truffles instead of white. Unlike the photo that still captures most of the essence of the dish that told me with my first bite that the chef used the best veal imaginable, I had the white truffle version in which our waiter shaved a generous portion of Alba white truffles before I massacreed the creation with my fork. Whether or not it was the combination and quality of the ingredients (and how often do you find white truffles AND caviar in the same dish?); the intrinsic nature of the truffle; or a fortuitous combination of the both, these truffle shavings were the most fragrantly powerful I can recall.

There’s near-unanimity among the regulars posting on the Chowhound “Piemonte” threads that Ristorante Il Centro in Priocca d’Alba is number one in their hearts. You won’t get any gruff from me about that. The restaurant dates from the 1950s and always in the hands of the Cordero family. When I first went in the late 1990s, papa Enrico was in charge of the dining room and the cash drawer while mama Elide did the cooking. Son Giampietro now runs the dining room along with his father. I rate Giampietro as one of the best maitres d’hotel I have encountered in my large universe of maître d’ encounters. If you go to Il Centro for lunch, you may miss him. Lunch time tends to be slow, and Giampietro could well be out tasting wines, adding to his profound knowledge of Piemontese wine–a welcome change from the taciturn, knowledge-deficient sommeliers I had to deal with at two of the other two restaurants I visited on my excursion.

It’s difficult to believe the Elide started out at Il Centro as a waitress. Soon after, however, by absorbing the work of Enrico’s mother, she taught herself the profession. Her cooking is what you could call “interpretations” or recasting the classics often to their benefit. Unlike the strict classicism or tradition you encounter all around Piemonte, Elide’s dish keep your palate in motion with a notable reliance on sweet and sour wine and vinegar flavors. As a result, the dishes are light and go down easy.

We were taken most by her rabbit “duss e bruss” (“sweet and tart” in the local dialect). Besides the depth and complexity of the sauce, I don’t recall among the scores of rabbit dishes I have had, one in which the rabbit itself was as tender and succulent, not to mentioned snowy white, as this one.

Giampietro was kind enough to send me a detailed explanation of the dish:

As the name says duss e brusc (sweet and tart), the main ingredients for this preparation are red wine, red wine vinegar, cacao and spices such as cinnamon, star anise and cloves. Formerly, we used the whole rabbit; nowadays just the legs, which better suits the stew-like preparation. Once the rabbit is carved, it is quickly pan-fried with salt and pepper, and deglaze with the white Arneis wine, just enough to start to create the sauce. In a bowl the red wine, vinegar, cacao and spices are mix together. When the rabbit has been pan-fried, and the sauce well-mix we put it all together in a roasting tray, and let it cook slowly in the oven at 180°C, checking it every 30 minutes until it is cook. After about 90 minutes. the sauce should be thick just enough to glaze the rabbit.

The origin of this dish is unclear, but Elide Mollo explains to the young cooks that this recipe originated in the wealthy families of Piemonte because cacao and spices were expensive and hard to find, and due to the boredom of eating simply-roasted rabbit tried to find new ways to prepare it. As a result, this particular sauce preserved the rabbit taste, yet the sweetness from the cacao and the wine reduction in combination with the vinegar gives freshness to the dish while making a combination that provides much more complexity on the palate.

Save some for me next fall!!!!

You can read Gastromondiale’s Madeleines of 2017 here: Editors and contributors.