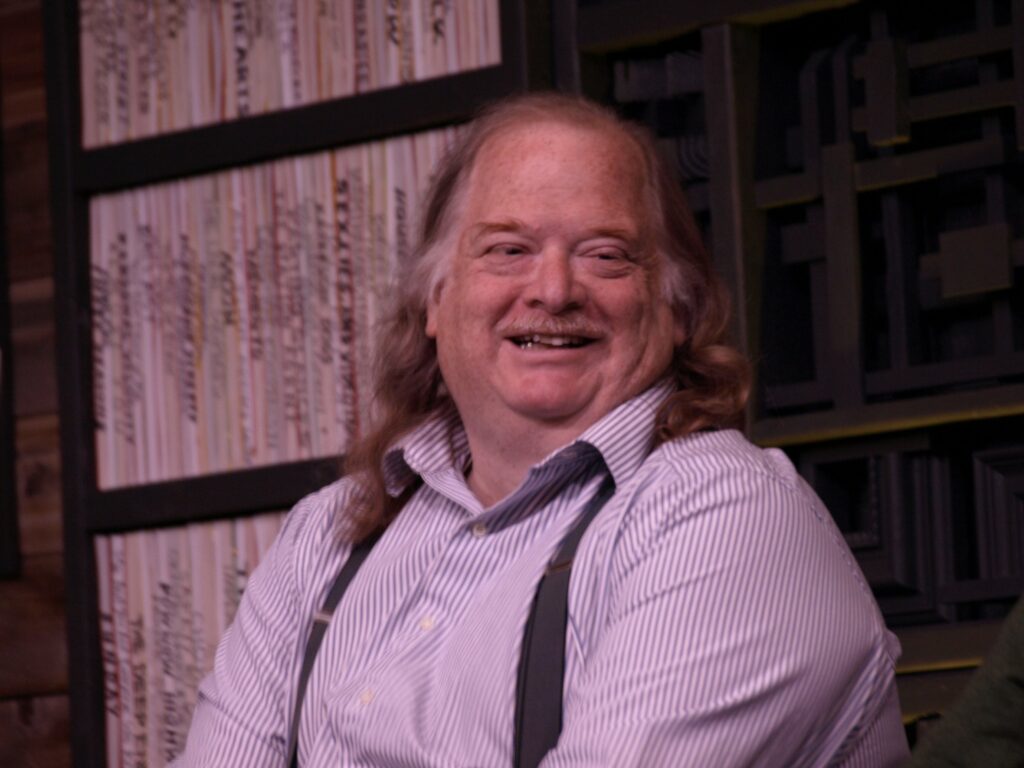

On the continuum of critical writings, restaurant reviews fall somewhere between the Venice Biennale and the toaster ovens in Consumer Reports. When the restaurant culture began to take off in the 1960’s, the review media barely existed, but with the expansion of the restaurant business, reviewing grew likewise. Despite the inevitable hacks and the legions of bloggers with their cellphone photos, restaurant reviewing can be a legitimate form of journalism, and like other kinds of passing-scene writing such as sports and haute couture, it has had some who are enjoyable to read beyond a review’s sell-by date. Also there is at least one master whose writings could conceivably remain immortal as the Annales school of historians that studies accounts of every day life will be having a field day with his output. That is Pulitzer Prize-winning restaurant critic Jonathan Gold who showed how much the form has evolved since The New York Times’ Craig Claiborne began in 1962 writing short, perfunctory descriptions and soon after giving one-to-three stars to New York City restaurants.

That was somewhat before the time I had the renowned Hungarian mass-communications scholar George Gerbner as a professor at the University of Pennsylvania Annenberg School of Communications. He often reminded us that “grasping and retaining” was the primary function of mass communications. However, this doesn’t apply to writing about restaurant meals since consuming them is about as ungraspable and unretainable as you can get. Add to this that there is no way to replicate in words (or pictures) taste, smell and texture, restaurant reviews are a breed apart from other kinds of culinary writings such as memoires, gastronomic travels, biographies, and food in history and cultures. In comparison, restaurant reviewing is constricting, constraining and by nature opinionated, all of which puts a premium on style, knowledge, experience, good writing, and, as Jonathan Gold had in spades, schtick.

Before Gold wrote his first restaurant review, his upbringing provided him with some of the prerequisites. He was raised in a family of five for whom dining out played an important part. While his father, a parole officer, couldn’t regularly afford to take his family to the big-name restaurants, the ones they did go to obviously gave Gold an appreciation of the various ethnic and marginal cuisines in Los Angeles, so much so that in his early 20s, he made an all-inclusive gastronomic tour of Pico Boulevard that encompassed more than 150 restaurants, which you can hear about in his own voice.

Gold’s father instilled in Jonathan a love of music, especially grand opera, which Jonathan would listen to driving his green Dodge pick-up truck around Los Angeles County. Gold was also musical, playing the cello in rock bands and studying music at UCLA, which surely influenced his succinct yet flowing rhythmic writing that was also helped by his early jobs as a copy editor. Later he traveled to countries whose cuisines were well-represented in Los Angeles such as Mexico, Peru, Korea, France and Italy, as well as to America’s gastronomic capitals. He owned more than 3000 culinary books, the overflow of which he kept on his staircase. For me, however, the most significant is that he had the rare, endearing quality I call a free-range brain. It endowed Gold with the ability to see concepts, hypocrisy, contradictions, and ironies while making connections and comparisons that elude most people. This gave his writing a satirical, occasionally witty, bent and a hipsterish, yet sophisticated, quality. It was these elusive intangibles that cleverly breathed new life into soup dumplings, Korean barbecue, and tacos while at the same time creating a nationwide coterie of mainstream media “cheap eats” reviewers who, unlike Gold, usually don’t pull off making the cuisine appear as enticing.

Gold also had an intellectual curiosity that made him at least conversant, if not authoritative, on a myriad of cultural subjects that were the sources of his comparisons and simile-filled writings. He also saw virtue and accomplishment in an open-minded, non-elitist way so that for him Dr. Dre was as worthwhile as Debussy, and Koreatown restaurants were as legitimate to review as those in Beverly Hills. Nearly all of his reviews, of which there must have been close to 2000, are infused with a joie de vivre that belied how seriously he researched each of them. (It was only when he was over the rainbow with a certain chef or restaurant that he become untypically breathy and fawning.) These qualities, overlaid on top of his rhetorical powers of describing how food looks and at least giving a strong notion of how it tastes, is what helped Gold receive his Pulitzer Prize in 2007 and in the minds of many makes him our greatest writer about restaurants, the likes of which the culinary world may never see for decades.

When Gold died, every tribute dwelled on his coverage of the marginal ethnic or immigrant restaurants he wrote about for most of his journalistic career, which began in 1984 at LA Weekly. However, there were periods during which he was a mainstream restaurant reviewer as he went back and forth between being an anti-establishment and an establishment critic, the latter particularly between late 1999 and late 2002 when he lived in New York writing for Gourmet Magazine and from late 2015 until the end at The Los Angeles Times where he covered all manner of restaurant. The extent to which he would deviate from the “Counter Intelligence” reviews in tone and otherwise can be seen in this one, which he wrote early last year, about arguably the most high-profile restaurant there is.

Although Gold wasn’t a pioneer (with the possible exception of food trucks) of analyzing marginal places to eat in (New York Magazine’s “Underground Gourmet” and Michael and Jane Stern’s Roadfood appeared several years before), he redefined and expanded the concept, having the good fortune of living in the midst of a spread-out incubator for ethnic or immigrant restaurants. Gold seized the opportunity and the circumstances, deservedly earning his place in journalism’s pantheon with “Counter Intelligence”, the rubric he used for his Los Angeles restaurant reviews, especially the myriad of the off-the-beaten-path ones, as well as American vernacular cuisine. In his fascination, he created restaurant reportage as enduring literature. (For a sampling of some of the best “Counter Intelligence” columns, this link will take you to the ones that got Gold his Pulitzer Prize while at LA Weekly, and if you want additional gastronomic entertainment, you can easily find on-line a copy of Counter Intelligence, a compilation of reviews published in 2000 with a cover blurb by Ruth Reichl: “…you could read it like a novel and be very satisfied”.

Running between 200 and 600 words, Gold’s “Counter Intelligence” reviews are tightly wound and crystalline. If you could measure them for body fat, the reading would be between 6-10%, which is what most athletes have, and like many of them, Gold’s writing is light on its feet. It’s almost impossible to come across a gratuitous or mundane sentence. Take this 2011 excerpt from his Beijing Pie House review:

You’ll probably start your meal with a cold appetizer or two, perhaps a plate of sliced celery spiked with soaked peanuts that act as little star-anise bombs, or a little sliced loaf of bean curd with soy sauce and slivered scallions, or a platter of oddly tasteless cold beef tripe with toasted chiles. There are dumplings, although the soup dumplings, xiao long bao, are on the stodgy side, and the pan-fried leek-with-pork dumplings are stiff and bland. You will get an order of the thick, handmade noodles, possibly in a thin, spicy beef broth; more likely as zha jiang mian: served plain and lukewarm in a bowl, ready to be tossed with slivered cucumber, bean sprouts and a tarry, pitch-black bean sauce enhanced with specks of meat. If you like the beef roll at 101 Noodle Express in Alhambra, one of the signal dishes of the San Gabriel Valley experience, you may find the beef roll at Beijing Pie House to be slightly austere. The beef itself is tender and elegantly prepared, smeared with a delicious bean sauce, resembling something plucked from a French pot au feu more than it does rough Chinese street food; but it is wrapped in a thin, delicate crepe instead of the brawny, oily pastry you’ll find at the uptown rival, like a beef roll you’d enjoy late in the afternoon, served with a pot of tea. You will like the “Homeland Meat Cake,” which sounds like the kind of fantasy Dick Cheney used to conjure up to cheer him through the long, lonely nights in his undisclosed location, but is actually a crisp, multilayered pancake of vast area, stuffed with thin sheets of a pink meat you don’t want to think about too carefully and sliced into wedges.

Gold juxtaposed long, loping but still-concise sentences with commas, hyphens, colons and semi-colons, sometimes pulling in the reins to end a review with a three or four word sentence. (His final LA Times column about Massimo Bottura and the lack of women chefs in the “World’s 50 Best Restaurants” rankings ended with “Modena is waiting.”) For nearly his entire career, Gold wrote in the second-person. By putting his readers in the scene, he gave them something of a bond with him. Gold also liked to begin a review or a paragraph with an “If you…”, a rhetorical device that propels a writer to get right to the point. He rarely used hype words such as “terrific”, “amazing”, ‘sensational”, and “incredible”, going instead for the concrete such as stating that a dish in a particular restaurant was the best of its kind in Los Angeles; revealing its appeal through the narrative as in his review of the Korean restaurant Lukshon: “Do his fried cakes of coconut rice with chili-shallot sambai steak au poivre rubbed with Sichuan peppercorns appear in any known cuisine? Probably not. But what matters is that they’re good”; or often simply stating that a dish was “fine”. Unlike nearly every blogger or unprofessional web-based food writer, Gold never let himself get bogged down in tortuous efforts to analyze dishes. He never second-guessed chefs, telling them where they may have gone wrong, engaged in dish minutia, or went through hoops to try and to describe what a dish tastes like. Dining room service was of no concern. All I could find in this regard is a one-sentence reference in his review in Gourmet Magazine of Manhattan’s Restaurant Daniel. (“The staff is so numerous, and so well-trained that if you accidentally knock a spoon off the table, someone may catch it before it hits the floor.”) His ability to make the reader conjure up the look of a dish, describing it as an art critic might a still-life, and invoking the salient qualities of the ingredients allowed for succinctness and being able to present the aspects of a restaurant in the minimum of words required. (I’m guessing that when he didn’t do this, it was because an editor told him he needed to write more words than were otherwise necessary.)

What also makes many of the “Counter Intelligence” reviews so durable and distinctive is the way they transport you to neighborhoods or communities that you would never think of going to. Often Gold would start his review by setting the scene in some downtrodden, if not ramshackle, part of Los Angeles that was brimming with commerce and street life. Such reviews often included a dégustation portion of travel writing. Also giving Gold’s writings permanence is their element of doggedly researched pedagogy. You pick up on something you didn’t know about a foodstuff, a preparation or ingredient nearly every time you read a “Counter Intelligence” review—for example this primer on Guatemalan food:

Next to the bakery Guatamalteca runs a quick-service restaurant specializing in $4. steam-table lunches and the Guatamalan antojito-like snacks called chapines. The plates lunches here are delicious, if basic: the chunky, tart beef stew carne guisada and the tomato-laced shredder beef stew hilacha, intensely-flavored longaniza sausages in tomato sauce that are better the fresher they come from the grill. And the musty Guatamalan innard stew rovocaldo. Sometimes the terminology can be confusing. What a restaurant calls a tostada, you’ll call a fried torilla smeared with beans, cream and a bright-purple mixture of beets and beet-stained cabbage-Guatamalans call an enchilada. Tamales are the soft airy kind, steamed on banana leaves, fluffed out with lard, filled with chunks of chile-stewed pork and the flavor is terrific, although the flavor might be a little off-putting if you’re used to the firmer Mexican tamales.

Or this, when he sometimes used the Q & A format at LA Weekly, where it often seemed that Gold wrote not only the “A’s”, but also the “Q’s”.

Dear Mr. Gold: In an article about haggis I recently read, the bit of trivia that I can’t stop thinking about is: “Lungs are prohibited for human consumption in the United States.” I can only guess that this is to protect us at places like Pink’s and Scooby’s; a hot-dog-ingredient law. Please tell me the truth about this mysterious lung-eating ban. —Geraldine Johnson, West Hollywood.

Dear Ms. Johnson: Out of all the possible parts of the ovine (and bovine) body, lungs are illegal because their vast interior is uniquely suited to bacterial contamination — really, if you managed to uncrimp one of the things, the surface area could probably be measured in acres rather than feet, which is great for the absorption of barnyard oxygen, but also like Dodger Stadium for the pleasure of barnyard bacteria. They are almost impossible to inspect for wholesomeness. I’ve eaten lung a few times — in Italy, cooks dip slices of calves’ lung into a light batter and fry them, and lamb’s lungs are part of the traditional Roman dish coratella, a rather good sauté of lamb’s innards with artichokes — and you aren’t missing much. Lung is all bland, light, cartilaginous crunch. And as for the haggis, of which lung is an essential albeit minor component, I refer you to the old joke about the man who, upon tasting the dish for the first time, remarked, “First I thought I had taken a big bite of dung, and then I wished that I had.”

Nothing else Gold wrote, however, eclipses this contribution to culinary scholarship: ‘Jonathan’s Gold’s 60 Korean Dishes Every Angeleno Should Know’

Not unlike a great art historian who can tell you in which museum or private collection any Italian master painting resides, Gold had in his head an all-encompassing map of Metropolitan Los Angeles restaurants large and small, cheap or expensive. More impressive was his ability to cross-reference dishes among extant and defunct restaurants so that, for example, in the now-76-year-old Chili John’s in Burbank, a review of which Gold wrote in the mid-to-late 1990s, Gold was able to mentioned five restaurants whose chili was inferior to Chili John’s:

But Chasen’s famous product was distinguishable from a bowl of Dennison’s only by a silver chafing dish and an 1800 percent price differential. ‘Uncle George’s Chili at Patrick Terrail’s late Hollywood Diner tasted as if Uncle George had been employed a by junior high school cafeteria in the Midwest. The “Kick-Ass” chili at 72 Market Street went better with a bottle of Bandol Rouge than it did with a cold longneck Bud, if you know what I mean. And Ken Frank’s chili at the old Le Toque, although exquisitely spiced was made with duck. Basically, if you want to taste real chili in Southern California, you’re stuck with chili cookoffs where you’ll find that championship chili is more macho than foodstuff……..or you could check out Chili John’s on the sleepy end of Burbank that has been the best place to go for chili for more than fifty years……..

Having worked together in the late 1980s and early 1990s at The Los Angeles Times, Ruth Reichl and Jonathan Gold were reunited in 1999 at Condé-Nast’s Gourmet Magazine, where Reichl had just been named its editor-in-chief. With Condé-Nast’s owner Si Newhouse lavishing very generous amounts of money on his magazines’ staffs, Reichl must have offered Gold a salary he couldn’t refuse. Gold’s assignments were mainly mainstream mid-to-upper range restaurants ranging from Manhattan bistros and trattorias to the budget-busting Daniel and Alain Ducasse at the Essex House. Reichl thus took Gold out of his distinctive milieu, making him a mainstream restaurant reviewer writing about the same restaurants as others, even though he was the best one doing so. As it turned out, Gold was at his best writing for the community of Angelinos about the various milieus, not for the national audience of Gourmet readers.

When I recently read all of Gold’s Gourmet writings, I realized that he was like a fish out of water and that his writing about more down-to-earth restaurants for an alternative metropolitan weekly was markedly different than for a magazine owned by a publishing magnate chock full of “good life” advertising aimed for an upscale demographic. Furthermore, in her effort to enliven the magazine, Reichl in both her exuberant monthly letter from the editor and hedonistic, lively content, most likely pushed Gold to write more “square” than “hip”, and upbeat rather than sardonic.

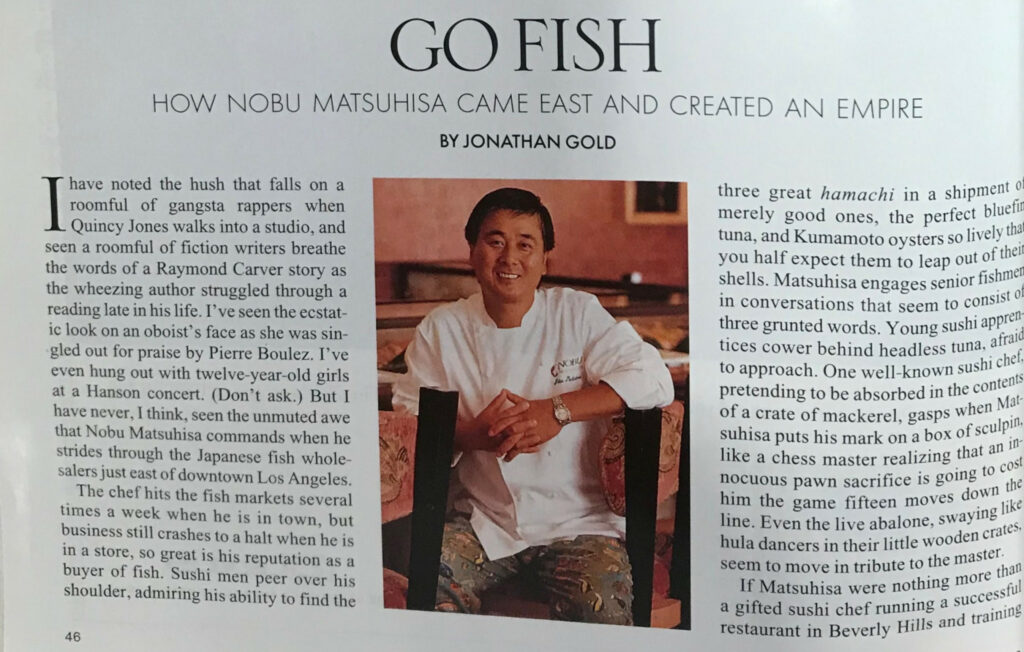

In Gold’s first review for Gourmet on Nobu Matsuhisa and his New York restaurants Nobu and Nobu Next Door, the length is several times that of the his “Counter Intelligence” ones. The Allen Ginsburg “Howl”-inspired opening reproduced here is almost a self-parody of Gold’s previous writing, as if one wanted Gold to hit hard on his trademark of invoking music and musicians in his writing. While Gold’s eye for detail and unparalleled ability to describe dishes is there, there is still an element of dish-droning. Nowhere to be seen, in many of his Gourmet reviews, are the satire and the snarkiness that Gold excelled at. Also often missing is the coherency, tautness, succinctness and stylishness of the Los Angeles reviews. Most vexing, though, was for Gold to invoke his untypical hero worship and fawning-over that one often read in other Condé-Nast publications such as The New Yorker under the then recently-replaced Tina Brown and Vanity Fair. To the reader who had no intention of dining at either of the two Nobu restaurants, the review was likely a slog; for those intending to go, there is still an element of telling you more than you may want or need to know, useful as the review may have been.

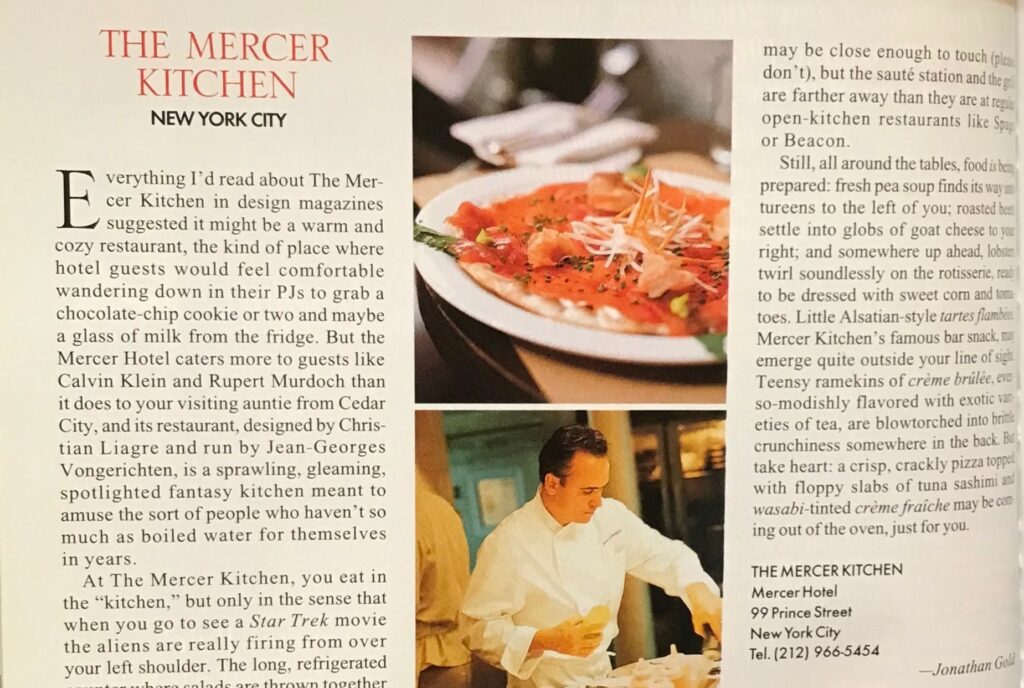

Reading Gold’s reviews one after the other provided insights that reading them a month apart wouldn’t have. What struck me most is the unremitting, if not effusive, praise that Gold bestowed on nearly every restaurants he reviewed. To read the Gourmet reviews this way is to come away with the notion that New York around the turn of this century had arguably the best restaurants in the world, on a par with Paris or the best in Italy. Nonetheless, there were some notable and endearing exceptions to Gold’s upbeat reviews such as his second review (October, 1999) where he took a pot shot at Jean-George’s Mercer Kitchen in which he shows no mercy, using the occasion to parody the mismatch between the restaurant’s name and its actual kitchen.

Two months later Gold, who also knew his wines, took on in a review of the wine-centric restaurant Veritas a class of dining wine freaks he calls Grape Nuts. The opening paragraph of the review is priceless in how it nails, mocks and roasts a certain type of wine collector.

From time to time many well-established restaurant reviewers unload on a restaurant. Sometimes one will do it to a restaurant in a foreign country, other times to restaurants that can take the hit. Fortunately, nearly every reviewer passes on a restaurant if going negative would do irreparable financial harm. In the case of Gold’s one scathing review in Gourmet, he skewered the Central Park South restaurant Atlas and its chef Paul Leibrandt perhaps because he had the cover of the three (out of four) star review by Ruth Reichl’s successor at The New York Times William Grimes that he wrote five months before Gold’s. The Times review begins:

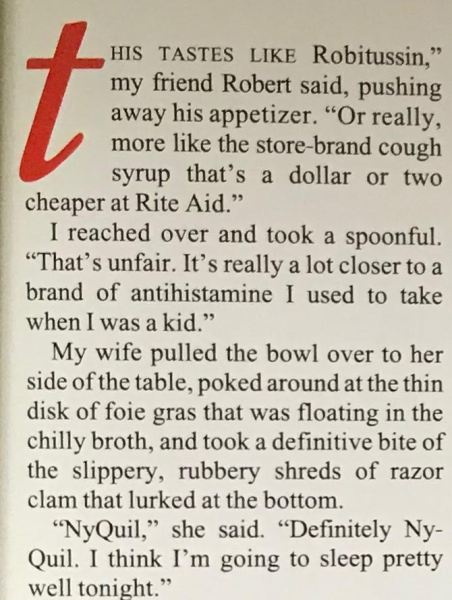

When it’s Gold’s turn, he starts off with satire as outright comedy:

When Gold’s wife Laurie Ochoa become the editor-in-chief of LA Weekly, she and Gold came back to Los Angles in late 2002 and began a second stint working together that lasted nearly ten years, followed by his return in 2012 to The Los Angeles Times when his wife become its Arts & Entertainment editor. The return to LA Weekly saw his writing at peak form as symbolized by his Pulitzer in 2007. Reviewing for an alternative weekly gave him the freedom to have opinions and likes and dislikes that he wouldn’t have after a while at The LA Times. It wasn’t as if he became America’s A.A. Gill with a hatchet, but from time to time he criticized or satirized certain macrocosmic elements of contemporary dining that nearly every mainstream reviewer avoids. He expressed a disdain for many-course tasting menus, describing them as providing nothing beyond “sensations”. In his review of the Umami Burger chain (He liked the burgers) he did a take on what you might call “Molecular Gastronomy Goes to Hamburger U.”

Whether intentional or not, this review appeared seven days before a lengthy article Gold wrote for the Wall Street Journal’s magazine WSJ Weekly in which he contrasts two “hot” avant-garde restaurants, Alinea and Noma, the former America’s shrine to molecular gastronomy and the latter in Copenhagen to foraging. What’s most remarkable about the article is that it may well be the best ever written about these two restaurants, and that Gold did it without expressing any opinion about anything he ate. (Note: This link may or may not give you the entire article with a browser in an incognito or private mode).

Back at the LA Times for his final six years, Gold reviewed all manner of restaurant from the ethnic to the expensive. There was somewhat of a difference, though, between these reviews and those from LA Weekly. The deft descriptions and, for the most part, his musings remained. Lacking was some of the whimsy and the hipness. The LA Times reviews seemed to carry a mandate from above that they be more user-centric or that Gold spend more words writing about the dishes one could order. As such, the reviews did not differ widely conceptually from those of good writers at other big-city newspapers. He also began to reposition himself to chronicling and being more receptive to aspects of the food zoo created by celebrity chefdom; chemically-modified dishes;, awards, competitions and contests everywhere you look; rank-order and other kinds of lists; and the empire-building in the restaurant world.

Besides reaching a larger readership, Gold became even better known from documentary filmmaker Laura Gabbert’s City of Gold (2015) which played in 40 markets. It was also around the time that Gold started to hatch plans with Australian Angus Dillon, who Gold met in Sydney at one of Dillon’s “Good Food Month”s, to launch a similar event in Los Angeles called the “L.A. Times Food Bowl”. Begun in May 2017, the annual month-long festival stages around 200 events including pop-up dining, a night market with food trucks and stands, a film series, lectures, tastings, and more, all of which from 2018 are listed here.

Having put together nearly three-quarters of the event, Gold went from being an observer or chronicler of the food world to becoming a significant part of it; or put another way he evolved from an anonymous restaurant reviewer to making business deals with many of the world’s most celebrated chefs that he might have one day reviewed.

We can never know how his reinvention would have further unfolded: Food entrepreneur? A media Food Network or Anthony Bourdain-type? Writing other kinds of food narratives? (In 2016 he signed a book contract with Harper Collins’ Ecco Press for an unrealized memoir with the working title “Breakfast on Pico”.) Whatever it would have been, his situation was becoming much more determined by the emergence and rapid change or dynamism in the chef and restaurant worlds than any one person’s role in it, even one as outsized as Jonathan Gold’s.