I had a fascination with gastronomy first piqued more than a decade ago by Vedat Milor and Mikael Jonsson’s unequalled blog, Gastroville. The whole website was testimony to the widely acknowledged idea that a good dish starts with good ingredients. Despite trends at the time, Gastroville also included harsh criticism of modernist restaurants.

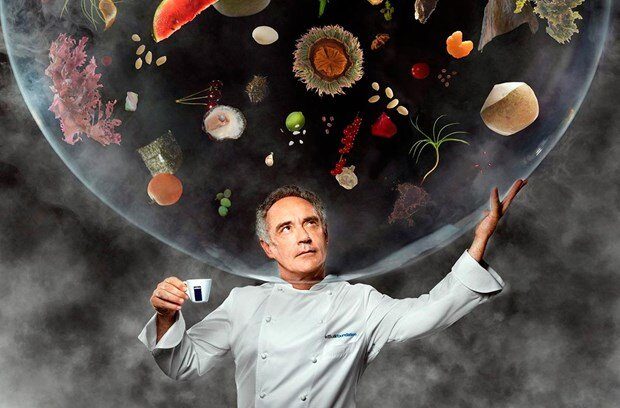

This stance underscored an increasing tension between ‘ingredientistas’ and ‘modernistas’ as to whether culinary actors should adopt an ‘ingredient-oriented approach’ or a ‘technique-oriented approach’. For modernistas, the ingredient-oriented approach correlates with a boring, mechanical race to source top quality ingredients. On the other hand, avant-garde chefs with a technique-oriented approach aim to go beyond simply sourcing quality ingredients, to direct their attention to elements of surprise and creativity.

Perhaps, this is a false dilemma, although we should recognise that both approaches can conflict in certain circumstances. It is understandable that if the aim is to be novel and creative, it may not be imperative to pay attention to sourcing top ingredients. Or, can we delude ourselves into believing that we are working with good ingredients? At this point, I would like to ask whether we can theorise a bit on what qualifies an ingredient as “good”. To make this as enjoyable as possible, I will construct a hypothetical discussion with Gastromondiale founding fathers, Mikael Jonnson and Vedat Milor.

DISCUSSION

Besim Hatinoglu: Vedat and Mikael, thanks for joining me to discuss ingredients. Perhaps, we can start with the following question: is it really possible that a chef at a major gastronomic restaurant can neglect working with quality ingredients?

Mikael Jonsson: Indeed this is often the problem with many of the Spanish “modernistas”. There is rarely any clarity or definition in the tastes at these places. On top of this, the multi-course menus offer many dishes based on inexpensive and pedestrian ingredients of not particularly good quality morphed beyond recognition and beyond culinary interest. The portion sizes of more noble produce are often too tiny to offer any gustatory highlights. Beyond the first bite, the food is rarely particularly appealing and personally not something I want to eat more than once: flavors come across as muted or artificial and very often there is a lingering aftertaste that effectively kills the next dish or in some of the worst cases the next couple of dishes.

Anyone who was lucky enough to dine during the 80s and 90s will attest how much the standards for the use of quality ingredients has deteriorated over the years at the top restaurants.

Vedat Milor: I agree with Mikael. Anyone who was lucky enough to dine during the 80s and 90s will attest how much the standards for the use of quality ingredients has deteriorated over the years at the top restaurants. Many Michelin two to three star chefs today, especially in Spain, but also in Italy, and also in France (post-2000 Veyrat and Gagnaire) are guilty of not respecting their ingredients. They either try to make a carrot taste like a tomato through techniques, such as morphing, or they do not respect the texture of an ingredient and go overboard in carrying out their experimentations, or they complicate dishes too much and try to marry discordant flavours, thinking that they are being “creative”. That being said, there are exceptions to this phenomenon. In the last 20 years or so, and especially in the 2000s, restaurants in America have progressed a great deal in upgrading the quality of the products that they serve, i.e. fresher fish, hormone-free meat, and seasonal fruit and vegetables. They are of course not on par with the Continent, but I think that they have progressed.

B.H.: Subject to minor exceptions, you both would argue that the overall quality of ingredients has decreased at the top restaurants. And I would argue that this is in line with the shift towards the pursuit of different values in gastronomy. Novelty and creativity are the dominant values now. As I said, it’s no surprise that ingredient quality is not the main concern any more. On the other hand, I also find it puzzling because you are subjected to long-winded speeches about how such restaurants source particular ingredients. To appreciate that the quality has decreased, we need to understand what makes quality ingredients and how they combine with each other in a dish. What makes a good ingredient? There are various factors at play here. For example, time is generally a major factor and its significance may depend on the context. Let me explain: Vegetables will have a peak time, and it will matter whether the producer is knowledgeable of this fact. It will also matter that a chef is competent enough to know whether the produce is fit for the purpose. Let’s take cattle as an example. “Butcher adds value in ageing and if required butchering to your requirements. The butcher stage can be done by some restaurants if they have facilities and skill set.” Time is perhaps most important when you find a great product, but it needs to travel. Some products will not lose much by way of quality, while it will prejudice other products substantially.I think we can call this the temporal aspect of ingredients. It may be stating the obvious, but regarding this last point, let’s start with whether freshness is a desirable property for ingredients.

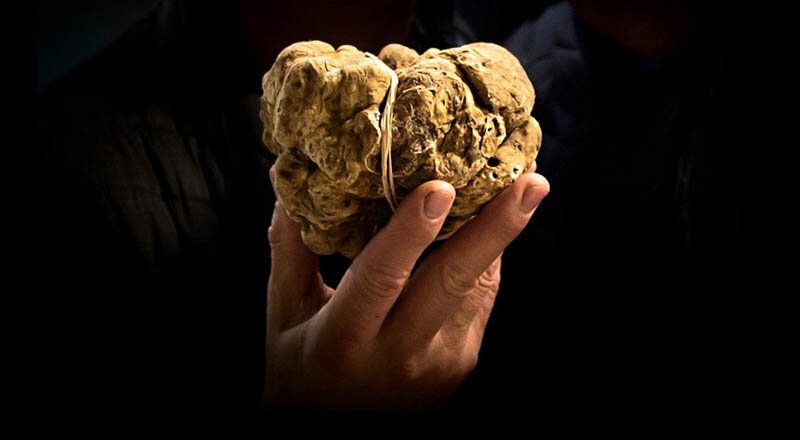

V.M.: It is impossible to give a general answer, but broadly, yes, freshness is vital. Take tuber magnatum as an example. Freshness clearly matters. Truffles which are not consumed within a week or so start losing their aromas and the texture becomes softer. I am afraid most of the truffles we eat in the States are simply not on par with what you get in the reputable places in Piemonte. Of course, the same applies to top restaurants in other parts of Italy. I remember visiting Da Vittorio once. As soon as we were seated in a very nice corner table in a beautiful cozy room full of flowers, all my senses were awakened and I almost had a headache from the intense perfume of that most intoxicating product on earth, the white truffles from Langhe. I could not see them, but their aroma was all over. Upon my questioning, our gracious captain Signor Nicola whose qualities would reveal themselves gradually but surely into the long journey into the wee hours of the night, showed up with a basket full of incredibly aromatic truffles, each weighing a pound or more. They had come the same morning, as this was a Thursday, and the restaurant is closed on Wednesday.

B.H.: Freshness as a parameter for theorising ingredients may be problematic when it comes to general categories such as seafood.

There are numerous exceptions to the common intuition, that is “serve seafood fresh”.

V.M.: I guess one does not have to paint the sea on the plate by using artificial emulsifiers or by mimicking the sound of the waves to create theatre. Seafood is at its best when it is fresh, least cooked, and served without denaturing it. This time let’s take langouste or spiny lobster as an example. They are of very high quality in Catalunya. For some, the best example comes from Cap Creus where the water is cooler than Arenys de Mar. You can simply boil langouste and devour by dipping it in the super olive oil seasoned with freshly ground black pepper. Or consider the small scallops from Galicia, called zamburiñas. Galician scallops may be among the very best in the world, together with scallops from Brittany, France and Hokkaido, Japan. However, Galician restaurants have a tendency to overcook the fish and shellfish. The zamburiñas are perfect when cooked properly with the attached roe still pink, proving their freshness. However, there are numerous exceptions to the common intuition, that is “serve seafood fresh”. I think Mikael is more qualified to draw those distinctions.

M.J.: Yes, we should distinguish between different types of seafood. For example, I never ever buy frozen squid and I complain when eating it in restaurants. I frankly don’t understand why chefs of some starred restaurants bother serving ingredients that so obviously are of inferior quality, at least in relation to the real deal. I guess another really good example is red mullet. First and foremost, it has to be super fresh. In my opinion a red mullet is best eaten the same day it was caught. The body should be literally rigid and the scales tight and the eyes clear and glossy. The taste of a fresh striped red mullet is a profound taste of the sea. It has no fishy taste to it whatsoever but an iodine flavour that for me evokes the feeling of being on a boat in the Mediterranean on a windy day.The flavour rapidly changes to one of iodine and fishiness and for those who know what a red mullet can be like when ultra-fresh, it can be repellant to eat when not ultra-fresh. The texture also changes rapidly. A very fresh red mullet will have a firm, yet translucent texture whereas a not so fresh one will have a more cotton-like and mushy texture. If bought very fresh but it, for one or the other reason, cannot be consumed immediately, it is best to clean and fillet it and store the fillets wrapped in plastic so they don’t dry. The content in the stomach easily starts smelling bad and the fish easily and quickly gets a rather nasty taste from this. In this sense, we should contrast it with, say, Dover sole or turbot that will get better after a few days in the fridge because this helps the flesh to relax, flavours to meld, and for gelatine to mature.

V.M.: As Mikael said, Turbot must be matured a bit. The same applies to lenguado. It needs 5 to 7 days for its flesh to soften and for its skin to separate from the body.

B.H.: I believe we can say the same for game such as becada (woodcock), which is referred to as “queen of the forest” by the Spanish gastronomes. Vedat once told us in detail how Iñaki Camba of Restaurante Arce in Madrid prepared it. He hangs the bird around a week to 10 days in order to bring out the intense, metallic and gamey taste. How did that change the taste?

V.M.: With that technique, the result is truly outstanding. It is a reminder to all of us how the less manipulated non-industrial and natural food of our forebears must have tasted. It is the very opposite of the bland meat we eat on a daily basis, and the sheer taste of Arce’s woodcock with its long faisandage (hanging period) challenges our very notions of what food should taste like, and it is a shock to the taste buds. But this is a real and positive shock, not unlike the artificially created shocks of the modern chefs who test the limits of manipulating raw materials by borrowing industrial methods from the food industry and experimenting with textures. Of all the best becada dishes I have eaten, including good ones at Coque, very good ones at Goizeko Kabi, Casa Nicolasa and Asador Etxebarri; and outstanding ones at Chateauvieux (near Geneva), Zuberoa and Ca l’Enric, Arce’s version clearly belonged to the top category.

B.M.: And of course, seasonality…

V.M.: One of the delights of being in Istanbul in the Spring is the chance of eating what, in my opinion, is the most flavourful turbot (called kalkan in Turkish) on Earth. Turbot is a fish that I order often in France, Spain (rodaballo) and Italy (rombo), and I find the turbot from the Atlantic in general superior to the Mediterranean variety, but not quite on par with a Black Sea Turbot caught in the Marmara sea. Indeed the dense and meaty turbot from the cold waters of Brittany is quite similar in taste to the Black Sea turbot that is highly prized in Istanbul in Spring. Unfortunately the increasing popularity and astronomical prices of this noble fish have led to its widespread farming, and fish markets in Istanbul are now filled with turbot farmed in the Balkans, especially Bulgaria. Although it is still a tasty fish, farmed turbot, which is brownish in color, is quite bland compared to the wild version. The season for wild turbot starts by the end of February, and those in the know think that this fish is fattest and best during the month of March when it is caught in the cold waters of the Bosphorus. The season lasts until early June or so, until the arrival of the hot summer days, and if you ask for turbot in Turkey past early June, you will either be served a frozen or a farmed fish. Obviously, I don’t recommend it.

Seasonality is a clear-cut issue when it comes to vegetables. We wait for the right season, the right moment for vegetables to reach their optimal form. A great producer will bring its produce to such form.

M.J.: Seasonality is a clear-cut issue when it comes to vegetables. We wait for the right season, the right moment for vegetables to reach their optimal form. A great producer will bring its produce to such form. For example, the most famous asparagus producer not only in Vaucluse but also in all of France is perhaps Robert Blanc in Villelaure outside Pertuis a 50 kilometres north of Aix-en-Provence. Blanc sells his asparagus under women’s names such as Brigitte and Danielle. There is a bit more to the names though. They are named after celebrities. Brigitte is voluptuous as Brigitte Bardot, Danielle is grande like Danielle Darrieux and Mireille is small like Mireille Mathieu. Marketing gimmickry? Maybe, but they are exceptionally good and prices are accordingly. The large Vaucluse asparagus has very different taste nuances and textures when raw, when semi-cooked and when cooked.

B.H.: Mikael, you said that a great producer will bring its produce to top form. In line with this, a final temporal aspect relates to recognising the life cycle of each animal. For some animals, it can be quite early, while others may be appreciated more when consumed at the final stages of their lives. Mannix’s roast lamb and Etxebarri’s fantastic txuleta made with authentic Rubia Gallega come to mind. The former is appreciated most when the lamb is quite young while the latter retires as a dairy cow and grazes in the grass for a year or so before it is slaughtered. Also, we can identify another significant criterion that contributes to the quality of a product: the breed of the animal.

M.J.: I have been running experiments with different lambs from various appellations. I made several of those experiments and came to numerous conclusions. For example, Pauillac lambs are at their best between 60 to 65 days in terms of texture and fat structure. I also think that 15 days is the right time to eat them after they have been killed. L’Agneau pré-salé lamb is generally commercialized at a slightly older age, that is when it is around 120-200 days old. Pré-salé meat benefits from aging. It may not be sold to butchers before three days after slaughter. Two weeks after slaughter the texture of the lamb shows an exceptional tenderness and juiciness.

V.M.: In my opinion, the best lamb in the world is eaten in Ribera del Duero, Spain. The reason is simple. The Castilian style milk fed roast lamb from the churra breed is one of the true culinary treasures known to mankind. Typically the lamb is about three weeks old (the Mannix version was 20 days old). This is true spring lamb, and the meat is tender and juicy. About two quarters of baby lamb are roasted/baked in a semi-circular baker’s clay oven lit by wood fire. Clearly this method comes from the cooking of the mechoui lambs in North Africa and was brought to Spain by the Moors. But the mechoui lambs I had in Algeria were drier in general, and the fact that top asadors roast the lamb slowly in low heat for hours, dousing them with a little water when necessary, may explain the eventual tenderness. It is in fact so tender that, as was demonstrated to us in Mannix by owner Marco Antonio, a sheer touch with a fingertip suffices to separate the bone from the meat before quartering the lamb, and the meat is so tender and intensely flavourful at the same time that it has to be tasted to believe how good lamb can get. Were I to rank the best lamb dishes I remember to date, this would rank alongside the 6 weeks old Lozere lamb prepared by old Jamin/Robuchon in a salt crust. Sure, they are less refined, but at least equally tasty. I still do not believe that the pré-salé from Grevin prepared by Mikael can surpass this level, but I will suspend ultimate judgment until I have the privilege to taste it.

B.H.: These are all success stories. Can you tell us about any major failures?

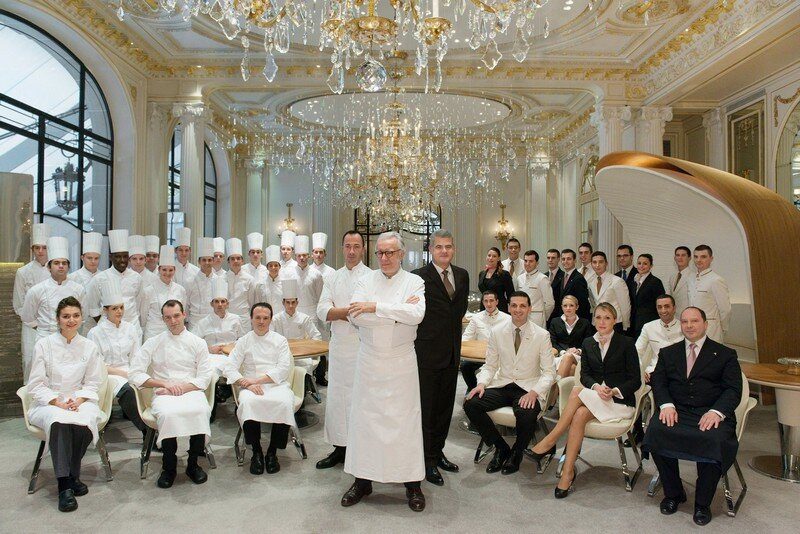

V.M.: I remember having a significant issue at Alain Ducasse au Plaza Athénée with a lamb dish around 15 years ago. It was not that the association between the main and supporting elements was problematic. The problem here was the quality of the 6 weeks old Limousin lamb, which was not as succulent and tasty as one normally expects from suckling Limousin lamb. Indeed the preparation, which has been inspired both by Italian (farro and lemon peel) and North African (with dried nuts and fruits) traditions, was well thought out and synthesized, but unfortunately given the chewy and rubbery texture of the meat, even a great restaurant like Ducasse could not create a great dish. The problem here may be the fault of the management rather than the chef. This is because, since the lamb is listed in the printed menu, even if the particular shipment is not of the highest quality, the chef may be unable to take it off the menu until he receives a shipment to his liking. This is certainly not the case in some other temples of haute cuisine in Paris, such as L’Ambroisie and Arpege, where the chefs are also the owners. These restaurants typically attract a gourmet clientele who will not be disappointed if Monsieur Pacaud or Monsieur Passard does not cook a dish printed in the menu if he is not satisfied with the delivery. Alain Ducasse, on the other hand, attracted a more mixed and possibly less discriminating clientele, and they may have a harder time to explain the absence of certain luxurious ingredients to their international clientele.

B.H.: Thus far, we have touched upon some fundamental temporal aspects of what makes a good ingredient. Terroir or locus is another significant factor that determines the quality of ingredients. To be more precise, where a product is grown or caught in general has a substantial impact on the quality of the ingredient. Of course when we say the location of where the product is grown, this includes several factors ranging from the temperature to flora or what food is available to the animal. We know that chefs would like to source from the terroir closest to them and this terroir generally corresponds to their national borders. For example, as Mikael puts it, eminent British chefs with a style that could be called British with clear accents from the British terroir strive to achieve this hard task. It is a hard task because while there are extraordinary ingredients to be found with roots in the British terroir, they are not as plentiful as in Continental Europe, which has long traditions in producing such extraordinary ingredients. So, should they go to other locations to source better ingredients? Let’s leave aside this question for now, and turn to the initial inquiry. What impact does terroir have on the ingredients?

The lamb from the borderlands between Normandy and Brittany grazed on the salt herbal marshes, periodically drenched by seawater, and often whipped by the salty winds from the ocean.

M.J.: Vedat mentioned churra breed. In terms of terroir, let me refer back to L’Agneau pré-salé. It is a mythic word to many gourmets. The lamb from the borderlands between Normandy and Brittany grazed on the salt herbal marshes, periodically drenched by seawater, and often whipped by the salty winds from the ocean. Le grévin, grazed on the salt marshes surrounding the bay of Mont-Saint-Michel is perhaps the most famous of the four pré-salé lamb varieties or brands. The others are L’estran from the bay of Somme et d’Authie, the Agneau des herbus from d’Ille et Villaine and the Agneau des Havres du Cotentin from Havres du Cotentin. The total production is a little more than 10000 lambs a year. The lamb’s high consumption of salt and iodine results in a meat with a more tender and juicier muscle cell tissue. The difference is quite extraordinary. Also, the particular flora with more than 60 different herbs results in a very particular and distinctive taste that is not too pronounced by lamb-like flavours but rather by the fresh herbs.

B.H.: If it is undisputed that terroir has a major influence on products, it matters what sort of product it is. We can link this with our earlier discussion relating to freshness. If the local conditions are favourable to certain products in terms of quality, locavorism might make sense. If the product quality is not satisfying locally, and superior products can be transported without losing their quality, then locavorism can have extra-culinary value. Gastronomically, it would not make much sense. Perhaps, it is just a meaningless chivalry or a narrative to manipulate consumers at restaurants.

V.M.: Good point. Let me also say that I am not necessarily a fan of locavorism and the farm to table movement. Well, if you have a restaurant in Catalonia or Galicia, you may fare much better in finding high quality ingredients than in London and New York. But even then, you have to bring some ingredients from outside your immediate periphery if you want to achieve a certain level of complexity and richness in cooking. What matters most is the relationship you build with suppliers and how much you care and are willing to spend for transportation for perishable products. This said, I have dined in quite a few restaurants, especially in France and Italy, where young chefs are true advocates of locavorism, and they offer very high quality products. More often than not, one eats well, but not memorable meals in such restaurants. The problem with such meals is that one cannot help but compare the local product with the best example of the category. Local shrimp, asparagus, beef, potato, tomato, onion, etc., may be good or very good, but it is nearly impossible for any region of the world to have the very best of all. By the way, do you remember our conversation about spot prawns, Mikael?

M.J.: Yes, I do.

V.M.: Mikael is endowed with an exceptional palate and did not think too highly about spot prawns, because he considers them inferior to San Remo gamberi. The fact is that the red gamberi, which are caught in the deep and rocky sea in and around San Remo and also in Denia, Spain, are the most succulent and sweetest creatures on Earth if you can find the ones caught the same morning. To me they are more special than, say, lobster, but neither Mikael in London, nor a restaurant in San Francisco can have them transported without compromising the quality.

M.J.: In fact, morel mushroom is a great example to illustrate this. Once a reader observed that L’Arpege, L’Ambroisie and Lucas Carton served morels from Turkey. Restaurants said that the morels from France are not available in sufficient quantities and that the ones from Turkey were often of better quality. He harvested wild mushrooms himself, but mostly mushrooms other than morels such as cepes and black trumpets. He pointed out that they can often lose some freshness in the time it takes him to get back home. So he hypothesised that morels from Turkey must be at least 1-2 days old before getting on the plate and therefore should not be as fresh as French morels could be. This is another example of how freshness is not sufficient. The morels from Turkey are generally considered as superior. The quality is consistently very high. French morels can range from diluted and mushy to exceptional at best but even the best are “only” on the same level as the best from Turkey. On top of that French morels are significantly more expensive. It is easy to understand why the restaurants select the ones from Turkey. With respect to freshness, my opinion is that morels do not suffer from some storage. Actually I would stick out my noose and say that most of the time they would benefit from drying up a bit although they must absolutely not lose their humidity. But the time it takes to transport them to France and the extra days they may be stored before they are consumed are not likely going to have much negative impact on them.

B.H.: This issue relating to travel time can also be linked with our earlier discussion about seasonality. It is a product’s season somewhere in the world, but how does it fare to travel?

In today’s world where raw material can be quickly ordered and shipped to a far away destination, there is little reason to argue that chefs, except perhaps for chefs exploring the local terroir, should only use local produce in season.

M.J.: I had this problem at a major British restaurant. The root of the problem is that creativity may be more important than the ingredient quality. The menu was not particularly seasonal in the strictest sense. Out of season items on the menu I had include items such as dried morels with one of the desserts, cherries, almonds and peas. On the a la carte menu there were further ingredients that are clearly out of season, even if we go to France for ingredients sourcing, such as ceps (from the Southern Hemisphere?) and borlotti beans. One could argue that it is a bit troubling to stretch the seasons in this manner. It is usually an evidence of lack of creativity or imagination or it can be perceived as insecurity or a narrow repertoire of the chef. It is if certain taste combinations are so thought out that the chef does not know where to turn to replace them. In today’s world where raw material can be quickly ordered and shipped to a far away destination, there is little reason to argue that chefs, except perhaps for chefs exploring the local terroir, should only use local produce in season. On the other hand, it is arguably easier to find the most exceptional ingredients from a selection in season than from the produce imported in the off-season from far away. I have never ever anywhere tried green peas even remotely close in quality to what can be selected on the Southern French markets in season. Everything else that is imported from far away, with a less careful selection process and travel time invariably tastes bland in comparison. That being said, let’s not forget Vedat’s point about San Remo gamberi.

V.M.: Mikael, you said that working with out of season products is usually an evidence of lack of creativity or imagination or it can be perceived as insecurity or a narrow repertoire of the chef. This actually gave me some thoughts, but about something else. As I agreed with you, spot prawns are clearly not on par with San Remo gamberi. However, the spot prawns are the best I find in the States. I recall having a fantastic preparation by Joshua Skenes. He poached them alive in sea water and served them with a touch of coconut and lemongrass sauce. I also remember a tiny bit of fermented unpasteurized cow milk brushed on the shrimp (yoghurt) and ginger. On the other hand, I also remember that Crippa compromised the refined taste of the San Remo gamberi. He cut the prawn into three and then he paired it with a strong grape must and strawberry jelly. It was cloying to the taste buds and the inclusion of some agrumes(probably emulsified by agar agar) did not create a balanced dish but created a confused dish. What an interesting contrast, isn’t it?

B.H.: It is, and this reminds me of your criticism of the international style of cooking, Vedat. I know that you think very highly of Skenes as a chef and you rated him as one of the top three chefs in the States. However, his dishes could come within your criticism of international style of cooking. How did Skenes come to be an exception?

V.M.: Michelin 3 star restaurants, particularly the ones in Spain, often disappoint those of us who are looking for the equivalent of what we call terroir in wine, i.e. seasonal cooking rooted in a place, in a cultural-geographical context. There is no doubt about the following: all of the three star chefs have perfected their techniques; most of them execute dishes perfectly; most of them are masters of composition and conceptualisation. They are very skilled in presentation, and they mostly come up with great ideas about complementarity and contrast of different elements in a dish. They all have great technique, perfect execution, remarkable compositions, and creative conceptualisations. The missing element is the quality of ingredients and the identity of the cooking. Nowadays, you get asparagus in Fall, truffles in Winter, and yuzu almost always in many temples of haute cuisine, no matter where and when you are visiting the restaurant. The setting may be in downtown Manhattan, an isolated farmhouse in the middle of a scenic valley in Alsace, or a modernist building in an industrial working class town in Catalonia… The location does not matter. You will get the compulsory dashi infusions, yuzu and passion fruit foams, dehydrated and powderised root vegetables, second rate sauces thickened by jellified products (xantam gum and agar agar), some liquid nitrogen here and there, and, if you are unlucky, a clam or a pigeon or lamb cooked sous vide and tasting like cardboard. You will be bombarded with eight amuses, five entrees, three main courses, and three sweet confections, not counting the mignardises with the coffee. The service will usually be impeccable and the surroundings should be exquisite. After a glass of champagne, one white, one red, a glass of dessert wine, and maybe some digestive, you will feel satiated, happy, and a little drunk. On the other hand, let’s turn to an approach that is opposite of international cooking style. I want to draw an analogy with terroir driven wine. La Tache, for instance, is a great wine, but in some years one can see that because the winemaker did not try to manipulate the wine, it is not hiding some flaws due to the weather conditions that year. Likewise Chez Panisse is committed to cooking almost exclusively (truffles being an exception) with local ingredients and letting them speak, instead of spotlighting the chef. This strategy is like walking a very tight rope. On some of the days they can err in the direction of playing it too safe. Jean Pierre does achieve what is hardest to achieve in this context, that is he makes things look “simple,” but this simplicity is misleading as it hides the overall perfectionism. The perfectionism lies in the ways maximum taste is extracted from the ingredients given very precise cooking and in the way the tastes are calibrated to achieve overall greatness. This is what Skenes does. It is almost natural to him.

The truly incredible stuff just does not exist. You cannot pick up the phone and say, ‘Hey, I want this’. You have to find it.

B.H.: Skenes from Saison is a good example of this. He is strongly opposed to shipping quality ingredients from overseas. He dreams about picking and serving sea urchin right by the sea to his guests, if it were possible. He notes that: “When I pull a trout out of the waters of a creek in the mountains of Northern California and put it on a truck to get it to me at Saison, it changes by the time it gets here”. In his attempts to establish a true, terroir-dependent cuisine, Skenes changed from sourcing some ingredients from Japan to exclusively the local area. He prefers a specific local product that is great to a different foreign product, even if the latter is at the source better. “Before it was about shipment of a turbot from Brittany or foie gras from its conventional places. But now, we sort of realised that if you can get a wild duck and if it has great liver in it, then that is much more valuable than getting something shipped”. In Skenes’s case, we therefore see the transformation of a chef into a hunter-gatherer: “the truly incredible stuff just does not exist. You cannot pick up the phone and say, ‘Hey, I want this’. You have to find it. You need to go out to hunt or fish because that is the only way to make sure that you are getting the best product”. But there is another transformation happening, that is the transformation of ingredients into a greater whole. Good dishes start with finding or producing great products, but the process does not end there. As complex as the topic of what makes ingredients good, the question of what makes a successful dish may be even more complex. I think that, in his piece titled “Tokyo Journal”, David Kinch did a really good job encapsulating an answer to this: “The very best of Japan, specifically Tokyo here, has always offered a far away promise; one of incredible ingredients and a genuine reverence for them, the passionate individuals who procure them, coupled with a complex regionalism and the appreciation and respect for old traditions. A reassuring nod to the future added to all this and all the cultural connections, speak of only the very best culinary traditions.’’ We will attempt a longer answer in the next issue.

Very inspiring and informative. Thank you Besim, Mikael and Vedat.