Nothing has shaped my thinking and preferences in ambitious restaurant dining more than Restaurant Alain Chapel from 1974 until 1990 when Chapel died suddenly at age 53. It was thus an “Isn’t it a small world” moment when dining at Chef’s Table at Brooklyn Fare I encountered the sommelier David Chapel, the first son of Alain Chapel. At the end of the evening, he told me that I should meet his girlfriend Michele Smith. My wife and I had a few dinners together with them and were at their Bacchanalia wedding in a former chai in the Beaujolais town of Morgon.

I am joined in the interview by two of my Gastromondiale colleagues, the founder of Gastromondiale Vedat Milor (VM) and Alexis Papazoglou (AP), a wine contributor to the site.

RB: You spent ten years on the supply side of the wine trade as principally a sommelier and captain at Per Se and then taking complete charge of the wine program at one of the hardest restaurant in America to get a reservation, Chef’s Table at Brooklyn Fare. Before we delve into that side of the wine equation, fill us in on your new wine-making venture with your husband David Chapel that is unfolding in the Beaujolais region.

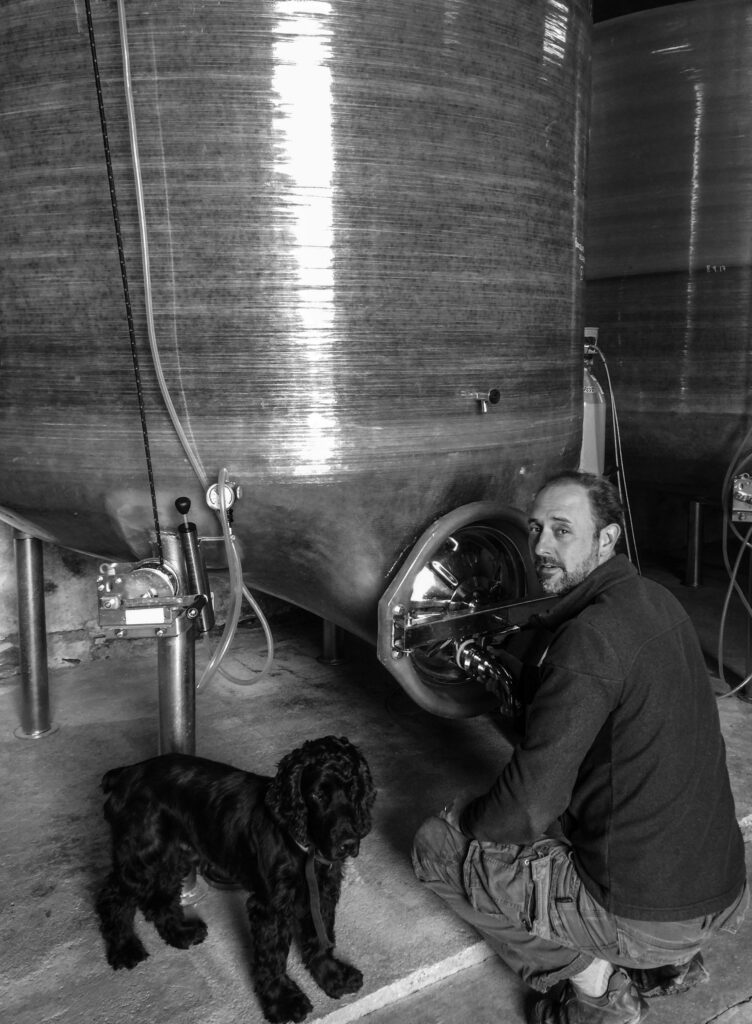

MS: Domaine Chapel is our Beaujolais estate in the cru village of Régnié-Durette. We produced our first wine – a 2016 Juliénas “Côte de Bessay” – in partnership with Mathieu and Camille Lapierre, winemakers and owners of the Morgon based Domaine Lapierre. Starting in late 2017, we will work from three hectares of vineyards in two additional crus. We will farm the high-altitude vines organically with manual plowing with the aim of restoring the land to a pre- chemical state. Our goal is to produce an elegant gamay that reflects the high-altitude exposition and complex granite-dominated soil.

AP: Why did you choose Beaujolais as the region to make wine in? What is it about wine from Beaujolais that you find most appealing?

MS: My husband and I met in Beaujolais in 2013. I was the wine director for Brooklyn Fare and on a 10-day busman’s holiday to visit vignerons in France. I had a tasting scheduled at Domaine Lapierre in Villié-Morgon in Beaujolais, but because of a simple travel incident, I arrived late. David, was working at Lapierre and came to meet me while I had a small bite in the center of town. To make a long story short, we’ve been together since that day. Just after we met, he moved to New York City so that we could be together. Two years later, we moved to Beaujolais to start our own winery. Even being an American, I’ve always felt at home in Beaujolais. After 15 years of living in New York City, Beaujolais was the only other place that I would have considered moving to. The wines are exciting, the terroir is extraordinary, and there is potential to purchase vines here. It’s not by coincidence that David was working in Beaujolais in 2013. The Chapel family has a long history here. In the 70’s and 80’s, in addition to being the owner- chef of the restaurant, David’s father Alain Chapel selected the wines for the cellar. The restaurant was in the Ain Department with close proximity to the Northern Rhone, Lyon, Savoie, the Jura, Burgundy, and Cerdon. His father had a great understanding of wine and carefully chose wines for his wine list with quality, taste and craftsmanship being the qualities that he valued the most. Many of those wines were locally known at the time, but have since grown to be synonymous with the region they are from. Wines from Henri Jayer, Domaine Leflaive, Comtes Lafon, Pierre Overnoy, Renardat-Fache, Jean-Louis Chave, Marcel Lapierre, and Colette Faller are seen on the old hand-written wine lists that David’s grandmother Eva wrote. To speak of the wine, gamay has an ability to play both cards at once. You can drink them young or you can age them and give them time to show their complexity. Beaujolais is meant to be drunk with friends and from a magnum or jeroboam. A single bottle is okay also, but never a half bottle. It would go against the nature of Beaujolais.

RB: We want our readers to better understand how the mind of a sommelier works. Let’s begin with how you go about in stocking and maintaining a serious wine list.

MS: My philosophy in building a wine list is to pair the wine selections with the food. For example, at Brooklyn Fare the menu changed daily, was mainly fish, and was heavily influenced by Japanese produce. There was a series of canapés served before the main courses. The flavors were delicate, nuanced, and dominated by acidity with a balance of sweetness and salt. The menu showcases the purity of pristine raw materials, so it was important to compliment these flavors and textures rather than dominate them. Seventy-percent of the wine list was white wine including a large selection of Champagne, Burgundy, Loire Valley whites and German Riesling. These are the types of higher-acid wines that pair well with the food. I stayed away from wines that would mask the flavors of the cuisine. I also chose to limit the scope of the wine list to several regions and to go in depth with the ones that were represented.

RB: How do you decide what to purchase to replenish and make changes in the list.

MS: For me, an ideal wine list should be a balance of traditional versus lesser-known producers at different price points. There are some wines that are meant to age and will be cellared for several years before appearing on the wine list. Other wines will be meant to move in volume, and these can change often in order to create more selections. If I buy two cases of a new selection, I am likely to use 12 bottles for wine pairings in order to cover the cost of the cases. This allows me to keep the other 12 to put on the bottle list or to put in the cellar for additional aging before adding it to the wine list when it is the optimal time to drink. The by-the-glass selections allow me to highlight lesser-known producers and introduce them to a wider audience.

RB: How do you go about composing the wine pairings?

MS: The wine list is built around wine pairings. That is, any bottle could be pulled from the list and paired with some portion of the menu. If a guest opts for a traditional wine pairing where the sommelier selects the wines, I prefer opening several bottles of wine to pair with a longer-format menu rather than pairing every course with a different wine. In my experience, too many wines result in palate fatigue and interrupts the flow of the meal. If there is one course that fits a truly amazing pairing that needs to be highlighted, I would make a short pour for that course which would be in addition to the pairing. The idea is to be flexible, keep it interesting, and explore different wines that may not be on the permanent bottle list. I never write wine pairings in advance because I prefer to open new selections on the fly without being limited. A large part of pairings is presentation, so I love to use magnums and jeroboams.

RB: Personally, I have never on my own opted for a wine pairing. Unless it is one of these private wine-collectors’ dinners where each participant brings a super-duper wine, I have never seen a wine-pairing offering comprised of great wines. Rather I prefer to go with a bottle or two and taste how the flavor changes with each course. What are your thoughts about pairings?

MS: I think that pairings are something that have developed out of the pre-set tasting menu format that an increasing number of chefs have chosen. If a restaurant can rely on a certain percentage of its customers to take a wine pairing, they can then project the sales for the evening or week if you have all of your reservations booked in advance. There is nothing inherently wrong with wine pairings. I choose bottles for my own wine-drinking, but that is my preference. From my experience, a lot of guests enjoy it when wine is pre-selected to go with the meal and they trust the sommelier to deliver a quality experience. It’s the job of the restaurant and sommelier to make sure the guest’s expectations are met and hopefully exceeded.

AP: Does choosing a wine pairing to match certain food dishes mean that wine always plays second fiddle in people’s gastronomical experiences?

MS: Wine is meant to pair with food, so in that way it is just doing its job. The quality of the wine should always be on par with the quality of the ingredients the restaurant is serving. That doesn’t mean that you have to pair Hokkaido sea urchin with Egon Müller Scharzhofberger (although that would be amazing), or black truffles with Montrachet, but you would need to pair the dish with a wine that brings out the best characteristics of the food.

AP: When you choose a pairing for yourself personally, do you start with the food you’ll be having or the wine?

MS: I will usually choose bottles earlier in the week, whether it is from a wine list or from my small supply. I’ll choose a restaurant that I have been looking forward to visiting. I’ll then ask that someone opens the bottles in a sequence that goes the best with what I am eating, but I never overanalyze the pairing. I think that people are sometimes get too tied up with finding the perfect pairing. Wine depends on your mood. If you allow yourself to relax and have a good time, your wine will taste good; your company will be great; your food will please you.

RB: Out of curiosity, what percentage of the clients at Brooklyn Fare took the pairings?

MS: I would say that close to 40% of the guests would request the wine pairing but it would vary and was unpredictable. One night, the entire dining room could opt for the wine pairing and the next night, we would sell all bottles.

RB: Do you think that most people who go with the pairings were not well-informed about wine?

MS: It’s a mix. I think that most people who opt for wine pairings are curious about wine and want it to be a part of their dining experience. They are allowing the restaurant to create every aspect of the dinner from the wine to food and service. There was no written menu with food descriptions at Brooklyn Fare, so even if a diner is knowledgeable about wine, it is difficult to know which bottles to select and when to present them. They put a lot of trust in the restaurant and me as the sommelier. The wine pairing was not written, so I had the liberty to change the wine pairing every service, and I would change the wines in the pairing throughout the night based on what went well with the menu and what I thought a guest would be into.

RB: What steps do you take to make the wine service profitable?

MS: The industry standard in NYC is a nearly a two-to-three times markup of the restaurant’s bottle cost. This is understandable because the cost of operating a restaurant is incredibly high. A successful and profitable wine program can keep a restaurant in business. If given the option, I prefer to put a lower mark-up in the range of twice to two- and-a-half. If the wine is priced competitively, there is a better chance of selling more bottles. This is better for everyone; the guest, the restaurant, and the winemakers.

RB: What role does wine storage play in the size of the list?

MS: The amount of wine storage space will determine the size of the wine list. The wines must follow the proper protocol of a cool cellar temperature, no light, and no movement such as vibrations from a subway.

RB: What about tasting the wines?

MS: I taste every single wine I open before the customer receives it to detect possible flaws. If a guest brings a flawed bottle to the restaurant, I always inform them about it and give the option to taste for their own confirmation.

RB: What are your sources of supply?

MS: Assuming that this restaurant is in New York City, I would work with 15 or so wine distributors in order to diversify the wine list. It’s ideal to have several sources for older vintages, with provenance being crucial when purchasing older wines.

RB: It seems like wine directors are a lot like art dealers, what with auctions, consignment, and buying from other dealers. Is it hard to find consignors? And what are the opportunities for mark-ups when you are buying at auction or from private cellars? Would a restaurant owner be happy with a 25 % mark-up on a wine he paid $1000 for? Also, are there a lot of people in the “business” of consigning bottles from their cellar?

MS: Ideally, a wine list will offer a library of older vintages to give it more depth and more options for the guest. Many wines require age in order to show its best and that requires time in the cellar. It is a challenge to find and buy older vintages of wine through a distributor because, first, most are selling the most current vintage available, and second, often when a winemaker releases older vintages, the wines are allocated before arrival. If you are able to get an allocation, it may be for a couple or a few bottles, and they won’t last long on the list. This is why sommeliers will rely on bottles from auctions and consignors. In a city like New York, it is not difficult to find someone who is willing to consign their collection to a restaurant. What is difficult is to be able to verify the provenance of each bottle. The hope is that sommeliers are doing the work to find out when and where the wine was purchased and the storage conditions. The pricing is worked out between the restaurant and the consignor, and generally the consignor can pull the bottles from the list whenever he would like. If a bottle is consigned for $1000 and sells on the list for $1250, there is still a $250 profit on a bottle that was low investment (just the cost of insurance) on the part of the restaurant. But generally, there will be more than a 25% markup on the wine. The markup varies drastically on different lists.

RB: Let’s assume that an accomplished chef and his backers opening a restaurant want you to create an ambitious wine list or inventory that will accompany a creative cuisine that has little or no ethnicity, but would include raw fish, pasta, vegetable dishes, fish, meat, cheese and dessert. They want to cover the gamut in current restaurant formats, which includes a selection of small plates, à la carte ordering and two or three tasting menus that also includes a cheese course. As this would be an up-scale restaurant with the range of the check for wine and food between $250 and $500 a person. The chef, business manager or investors come to you and say they want a first-class wine list/program and have a budget of $500,000. Would that put them in the same league as a Per Se, Jean-Georges or Daniel, or one of the several well-stocked restaurants in San Francisco? If not $500,000, how much more money would they need?

MS: It is difficult to determine the exact budget that one needs because you can manage with a $500,000 budget, but would need to rely more heavily on consignment which has no very little initial cost to the restaurant aside from storing matters and working out a contract with the owner of the bottles. One could also work with a budget of $2 million and use that money to build a list in which more wine is purchased and therefore is the property of the restaurant. This would be for the investors to determine based on their resources. A resourceful sommelier will build a strong program. A budget of $500,000 will allow you to build a base of the wine list and stock a well-selected, by-the-bottle and by-the-glass program of current vintage wine. The restaurants mentioned above have had many years to build a stock or reserve of older vintages that they purchased at the price on release and most likely when allocations were not as competitive. If you are trying to build a wine list that is on par with Per Se, Jean-Georges, and Daniel, the wine director would also need to rely heavily on consignment, auction houses, and purchases from private cellars and merchants, in order to build a selection of older vintages and wines that are no longer available from distributors.

RB: Now it comes the time to be specific as to which wines you would buy for our mythical restaurant. Do you have something like a template in your head that has you buying a certain quantity or percentage of a sub-class of wine such as Barolo, Chianti Classico, Chablis, Chateauneuf-du-Pape, and so forth?

MS: When constructing a wine list, I would consider the cuisine first and choose wine that pairs well with the cuisine. These wines would make up 90% of the list or more and would be the majority of what I would be recommending to guests and using for wine pairings. I would represent the classic wine regions, but also highlight their lesser-known neighbors. I may want to contrast a Barolo selection with a Valtellina Superiore from neighboring Lombardia. From there, I would look to put at least three vintages of wines at different price points under each category.

RB: How about the quantity of percentage along a price scale such as wines between $50-$100; $100-$250 and above $500?

MS: You have to represent all different price points because there will be guests who want to be on the conservative side and others who are looking to order wines that are rare and costly. I’ve had guests who had saved for an entire year in order to come and eat at the restaurant and others who would come several times a month and for whom cost didn’t matter. To make sure that the wine list is accessible to all clients, a large part of the list, around a half, would be priced between $40 and $99. These selections are wines that can be dynamic and used for wine by the glass, wine pairings, and by the bottle. The next category can be wines between $100-$250 which might be another quarter of the list, and then wine above $250 for the other quarter. The goal is to get everyone to have a bottle with the meal and make sure that cost doesn’t prohibit them if they want to order a second bottle.

RB: How important a consideration is the type of cuisine the restaurant serves or the chef makes?

MS: The cuisine is my first consideration. The wine has to pair with the food and be on par with the quality of the ingredients being served by the kitchen. This isn’t to say that you have to be limited and must for example, serve only saké at a Japanese restaurant. I would look to add wine that will enhance the food and not conflict with the flavors and texture: that is, wine with high acidity, with minimal oak flavors. In this case, I would look to Champagne from the Côte des Blancs, altesse from Savoie, chenin blanc from Saumur, Riesling from the Saar, chardonnay from Sonoma, aligoté from Bouzeron, pigato from Liguria, savagnin from Arbois-Pupillin, Assyrtiko from Santorini, petite arvine from Valle d’Aosta, a Corsican rosé or vermentina. There are plenty of other places to look for inspiration and no shortage of delicious, clean, salty, high acid wines from every pocket of the globe that will work well with Japanese cuisine.

RB: Within these groups, do you have specific winemakers that you just have to represent?

MS: For every recognizable, well-known, established producer on the list, I like to have a lesser-known producer from the same region who is making exciting wine and working well in their vineyards. These are people who are more or less known in their region already, although perhaps not as well known internationally. To a guest this could be a great discovery. Using Beaujolais as an example, when building a wine list I would want to have Domaine Lapierre as a benchmark because historically they have importance, and they continue to have relevance by producing some of the highest-quality wine. I would then add lesser- known producers, like Christian Ducroux in Régnié- Durette who has pushed agricultural boundaries and has some of the most incredible, bio- dynamically-farmed vineyards in all of Beaujolais, and Jules Métras, who is part of the next generation of young vignerons. He has been making wine at his father’s Domaine Yvon Métras and is now working all of his own parcels organically and by hand. He is producing the best example of the lesser-known cru Chiroubles and bringing change to an appellation that has historically been abused with excessive chemical treatments. He, along with a growing handful of others, is the future of Beaujolais.

RB: I am not always a big spender for wines at restaurants. When I am not, I always look for what I call “safe harbor” wines that to my mind offer some semblance of value for money. For me such wines are Chianti Classico, Rosso di Montalcino, and for white and red Burgundy, Santenay, and Viré-Clessé from the Maconnais, and on rare occasions a West Coast Pinot Noir. What are some of the popular or ubiquitous safe-harbor wines you like and which ones you would be apt to put on the list?

MS: In this context ‘safe harbor’ wines seem to be tied to classic wine- producing regions that are recognizable to most people who purchase and drink wine. I believe the quality-to-money ratio to be the opposite because generally, the more recognizable the region, the more the wine will sell for. Wines from lesser-known areas tend to offer more value. If you normally drink Puligny-Montrachet but find yourself priced out, you can try a chardonnay from the Jura. The value-to-quality ratio will be higher in the Jura wine. Some classic regions will still offer value, and really all of Germany, as the first example that comes to mind. If you love pinot noir from the West Coast, I would encourage you to keep drinking them because the wines are the best they have ever been, and producers need all of the support right now after the recent wild fires that devastated the region. If you were looking to drink a bottle from Sonoma or Napa, you could try the other non-pinot noir wines from a winemaker that you like. In this way, you are still supporting the winemaker, but also discovering a new wine. This is also a great case where the guest should defer to the sommelier. Most sommeliers drink a fair amount on their own time; they drink new and interesting wines for which they are always searching. At work, I may be tasting a Coche- Dury Meursault, but when I go to meet friends afterwards, we will be drinking Domaine de la Tournelle from Arbois. A sommelier may be fortunate at work to taste one of the best wines in the world such as a Chave Hermitage, but it’s more likely that you’ll be drinking an Eric Nicolas pineau d’Aunis on your own time. I give these as examples to show that all these wines are brilliant and that sommeliers are also always searching for quality and value.

VM: I have trouble matching wine to dishes that contain fermented milk products such as yoghourt, which is amply used in Turkish cuisine. Which wines would you recommend for such dishes? Also, what do you recommend with raw artichoke salad?

MS: These foods will pair with high-acid wines that cut through the lactic qualities of the food. I would choose Champagne, altesse, and Riesling with some residual sugar. A classic pairing for the raw artichoke salad would be Federspiel Grüner-Veltliner. Or I once paired an Austrian rosé Sekt, made from the grape blauer Wildbacher with this dish. The winemaker was Franz Strohmeier from Styria who successfully produces a zero sulfur, zero dosage, Champagne-method sekt with incredible fruit balance and strong acidity.

VM: As a wine lover and quasi-professional, I am taken aback as to why the sommeliers I like in the States do not enter the adobe of the great sherries of Sanlucar and Jerez which are a great match with all kind of dishes and are a relatively good value. These fortified wines cover a whole gamut of flavors and textures and can accompany shellfish, game, offal, jamon and what not? Is there a reason for their neglect by sommeliers?

MS: Perhaps a restaurant is limited by budget or space and therefore chooses not to include sherry, but most dynamic wine lists will have several selections. I think sommeliers are paying attention to sherry again. New York City just concluded“Sherryfest”, an event that celebrates and educates wine drinkers about the history, production, and pairing potentials. There is definitely an interest within the industry, especially in the US and London. If you want to see more sherry on lists, you should tell the sommelier. I never put half-bottles of wine on my list until a guest asked me. Although half-bottles would never make up a large portion of the list, I was happy to add a few selections for the guest.

VM: Am I too opinionated thinking that even the more interesting higher-acid California, Oregon and Washington State wines do not possess the mineral dimension you sometimes find in France, Germany, Italy, Austria, Santorini and elsewhere?

MS: Until about the last 10 years, many producers were focused on making wine that was popular on the market where fruit was the dominate characteristic. You can still find those wines, but there is another style that leans to mineral (non-fruit or wood) flavors, higher acidity, or freshness with a balance of fruit. Some producers that first come to mind are Céritas, Sandhi, Wind Gap, Enfield Wine Co. and Arnot Roberts. But the list is long, so that if you are interested, there is a lot to discover. The wines being produced in California have more to offer than just extracted fruit, and can match old world regions for their complexity.

VM: Talking about minerality, I find it hard to pin it down and even harder to talk and write about it (other than using terms such as saline, volcanic, sea spray, etc). What do you think about these terms and what do you think about the general state of wine description and writing?

MS: Mineralality is a code word for acidity intertwined with savory characteristics that are not derived from fruit or wood. Those who describe saline, volcanic, and sea spray can perfectly describe the characteristics of minerality in some wines. I like sea spray; I’ll use that in the future! I once sat in on a wine course and was asked to describe a wine poured in a blind tasting. I described the wine as tasting like rain water. The professor was adamant about the fact that rainwater has no taste, no smell, no character. But, if you close your eyes and imagine the smell of rainwater, the feeling of the air before a big storm, the smell of the air after, all of those qualities can be expressed and understood through wine. This is because wine is emotional, expressive, sensational and not necessarily rational or cerebral. You can call a wine nervous if it is holding back, not showing its full potential. You’re conveying a message using descriptive words or phrases, and someone who has experienced the state of being nervous will understand. If you evaluate and make things too literal, you lose the wine and you lose the emotion. As to the general state of wine description, I think there is room for more creativity and originality.

AP: What is your opinion on natural wine? Is it an ideological fad, or does this winemaking approach actually produce better wines?

MS: If you take the term ‘natural wines’ out of the conversation, it becomes less ideological and then becomes about what makes sense. The less intervention a vigneron uses, the purer the wine, if and only if, that wine has been made correctly. I think of it in terms of a chef cooking. You source the best ingredients; i.e.grapes that were farmed without chemicals; you use classic techniques (vinification) to bring out the best characteristics in the product; if you are working your vineyards well or in the case of a négociant, buying from someone who works with good farming practices; if you are working in sanitary conditions; if you are not adding chemicals to the wine; and if you are not using invasive filtering, then you are more likely to produce a wine that tastes good and will age well. On the flip side, if the wine you produced is clearly flawed because you were allowing nature to take its place and you didn’t intervene, then you just didn’t do your job. Winemaking is a skill that requires knowledge, a trained palate and lots of work.

AP: What’s a region or style of wine that is still underappreciated by wine lovers?

MS: California is misunderstood by some markets who want to label it ‘American wine’ with the old school idea that it will be rich, sweet, alcoholic when in fact the best winemakers produce the opposite.

AP: How did you make the transition from sommelier to winemaker? How does your vast experience in tasting wines from all over the world and the knowledge of different styles and winemaking methods that goes with it inform your winemaking practice?

MS: I assist in making the wine, but at this stage, I am more of an apprentice, cellar hand, and vineyard worker. My husband David is making the technical decisions this year. I am learning from him and others in Beaujolais. In the future, when I have more knowledge and am more certain, I will make my own cuvée. Now, I bring my experience of tasting, and I do whatever job needs to be done.

RB: I am getting a mixed picture about the state of wine offerings in restaurants in France. Some of the great restaurants in France have through the years have had their cellars diminished Some even offer little or nothing more than five or six years old. What do you think caused this?

MS: Many restaurants in France have been forced to sell their cellars in order to guarantee a salary for their staff, pay the purveyors, buy wine, and pay the TVA tax among other factors. Many of the great wine cellars have been sold off in part or in full, and much of it has been exported abroad. Historically, current releases would have been put in the cellar and forgotten about until they had enough age to be put on the list. Restaurants that have been passed through family generations are now looking at higher prices on wine that they previously bought for a fraction of the cost. The higher prices are caused by a fluctuation in the market value that has put wine out of the reach of many restaurateurs. It’s not that a restaurant doesn’t want to offer a library of older vintages, but if you no longer have a large inventory of aged wine, you are forced to sell younger wine that you offer the wine by the bottle or in wine pairings.

RB: From all of us, thank you so much for the time and thought you have shared with the Gastromondiale readers. No doubt they will be encountering the wines of Domaine Chapel in the not-too-distant future.