Neo-nouvelle cuisine is what can be seen as the logical progression of nouvelle cuisine, it is what some might call classical French with a contemporary twist or the adaption of technical progression and contemporary trends into French cuisine. Frothed sauces, micro-herbs, acidity, Asian products, sous-vide cooking or gels are some of the cornerstones of what makes it necessary for me to differentiate this certain style from classical Nouvelle cuisine. Neo-nouvelle cuisine is a logical continuity, something one could possibly call a “conservative revolution” of French cuisine. One of the representatives of this approach, admittedly in a rather conservative way, is Éric Fréchon, chef éxécutif at Epicure in Paris.

The most precise word to describe Éric Fréchon’s cuisine is perhaps precision. The delicacy ofFréchon’s dishes lies in its exactitude and accuracy. The reduction level of the sauces is perfect, as a matter of fact they combine superb consistency and clear structure, a structure that is reminiscent of the bold version of a good perfume. A sauce could have the clear citrusy aromas of verbena as a volatile top note and the freshness and fruity perfume of Burlat cherries as a base note providing length and a refined aftertaste bound together by a heart consisting of a reduction of duck jus. The products are some of the finest I have encountered and cooked in a way that is simultaneously accurate and manages to emphasize the exceptional quality and let it shine. Where a lot of modern restaurants do exactly the contrary, Fréchon’s cuisine relies strongly on product quality. Assuming that these products are the cornerstones of his cuisine, as a diner one will come to the conclusion that the superior objective is the composition of dishes where product quality is most evident and not overpowered by any other component. The main ingredient is never surrounded by more than three or four elements that do underline the centrepiece of dish.

One ofFréchon’s newer signature dishes is based on cooked langoustines. The tails are served chilled, at room temperature, and wrapped in a thin jelly of celery, topped with some caviar from Sologne and served on a delicate bed of yuzu cream. The cool temperature makes this one of the most perfect ways to start a meal. The langoustine’s iodine and nutty sweetness are the main component in every bite. They appear as clear as an azure blue sky with the caviar being used as a way to emphasize the iodine and add salinity to the dish. The celery’s sharpness is the most subtle counterpoint imaginable, present but never in a way that is distracting or an undesired complicity. The yuzu cream provides a tremendously elegant acidity that is, in a way, the frame for the langoustine’s glory. The citrusy perfume adds length, it is a finish stimulating the desire to have another bite long after being finished. This dish is exemplary for how well conceived and elaborated Fréchon’s dishes are.

Temperature, proportions, flavours – everything is composed with tremendous care resulting in pure harmony. This harmony is the greatest strength and weakness of the cuisine at the same time. Strength, because it makes everything extremely delicate, easily accessible and understandable. It is a cuisine that makes you feel not think. This harmony is Fréchon’s way to achieve his, from my point of view, primary goal – the absolute celebration of a product’s glory. What he does is as harmonious as a teenage boy and his beloved girl laying in a romantic room with roses and a chimney watching “Lost in Translation”. Weakness, because Fréchon decided to sacrifice intention on the altar of harmonious composition. The intention to renew is what made French chefs from former generations become iconic and made it possible to avoid that French cuisine became outdated. Senderens’ homard à la vanille was such a dish, as is Passard’s tomato dessert, Le Squer’s croquant de pamplemousse or Point’s invention of the “en vessie” cooking method. This leads us back to Epicure, where the most famous and most photographed, apart from the macaroni, is this poularde en vessie invented by Fernand Point – a dish not invented by Fréchon himself. Same goes for the stuffed macaroni with foie gras, truffle and artichoke, which is actually a creation of Jean-Louis Nomicos.

A meal at Epicure always starts with a trilogy of amuses bouches. At my last meal a chickpea cornet with chickpea cream had a little too thick dough and lacked complexity, while a frog leg perfumed with tandoori and served with a tandoori mayonnaise was a highlight – the frog leg crispy, the mayonnaise light and decadent simultaneously. A foie gras cream topped with sorrel emulsion was a most harmonious, enjoyable combination of liver and herbaceous flavours. A second amuse bouche is usually “jelly with cream”. Whether it is haddock with cauliflower and red onion jelly or potato with chive, you will encounter a great combination of acidity, sharpness, smokiness and lovely textural play of crispiness and onctuosité.

Another variation of langoustine consists of pan-fried Dublin bay prawns with piment d’espelette, a cream of carrot, a condiment of mango and onion. This obvious but utterly delicate symbiosis is served in an equally elegant, velvety cloud made with the claws, a hint of coriander and a pronounced acidity of yuzu. The saucing was some of the most impressive, complex and refined I have experienced over the years. Execution was almost perfect, the dish perfectly enjoyable. Nonetheless, I had the impression that Fréchon played a little too safe game with this dish.

Fréchon’s repertoire is huge, seasonality plays a big role. Except for the macaroni and the poularde no dish is on the menu all the year. Crab with tomatoes and its mayonnaise in summer is later replaced by a dish of purple sea urchins that is a most obvious hommage to Frechon’s roots in Normandy. The sea urchins are served with an egg emulsion and a sea urchin cream in a sea urchin shell-like bowl by Sylvie Coquet. Thin slices of crispy bread with seaweed butter are to be used like a spoon. The seaweed butter adds even more creaminess to the sea urchin melange and simultaneously works as a device to stress the iodine of the high quality châtaignes de mer. A dish all about the sea, about Norman coasts, iodine and natural sweetness.

As I regard technical precision as Fréchon’s greatest strength, I was kind of irritated with a lobster I had this winter. Actually the dish was perfectly conceived, but the claw was dramatically overcooked so that I wondered whether this dish would have been served with Fréchon in the kitchen. The tail, on the other hand, was perfect with lovely smoke flavours due to being grilled over chestnut shells. A sauce made from the head had great depth of flavour, length and was reduced until the very end – great craftsmanship. Celeriac tagliatelle glazed with a chestnut sauce added an earthy accord. Apart from the obvious error a simple, yet elegant and very good dish.

Whilst most of the dishes feel like Paris in an unashamedly neo-nouvelle-cuisine-esque, sometimes baroque way, there are some creations leaning more towards the Mediterranean and Spain. Rabbit and octopus with chorizo oil, lobster with anchovies, chorizo and olive oil, charred leeks with a lemon-scented oyster tartare. One of the menu’s least luxurious dishes and simultaneously one of the best representatives out of the category described above is merlan de ligne de Saint-Gilles-Croix-de-Vie. Whiting is a rarely used fish in high-end gastronomy, a cheap one most of the time and an immensely difficult one to cook. Fréchon’s uses the filets of very huge specimen. They are put on a tétragone of almond pain de mie and pan-fried, leading to a similar result as Pacaud’s viennoise de sole. The whiting does never touch the pan, as the fish-bread-combination is fried in olive oil with the almond bread on the bottom for about three minutes. The low temperature pan-frying on the bread results in a meaty filet with a perfectly crunchy crust and superb cuisson. This makes a result possible that otherwise would be rather difficult to achieve with a whiting. The fish is very juicy, cooked to perfection with great texture and a lot of character a technique like sous-vide can never provide. A layer of New Zealand spinach adds a herbaceous, fresh note. A vinaigrette of olive oil, chives, piquillos and a touch of Bombay curry makes this an extremely balanced dish with great textural contrasts and harmonious seasoning. The dish is cooked to perfection making it possible to elevate the whiting beyond its normal potential. At Lucas Carton I was served a similar dish (whiting cooked in galettes de sarrasin, spinach flavoured with curry, buckwheat cream) by the very talented rising star Julien Dumas that showed how slight technical imperfection and a less balanced, less appropriate profile can make a similar constructed dish less enjoyable.

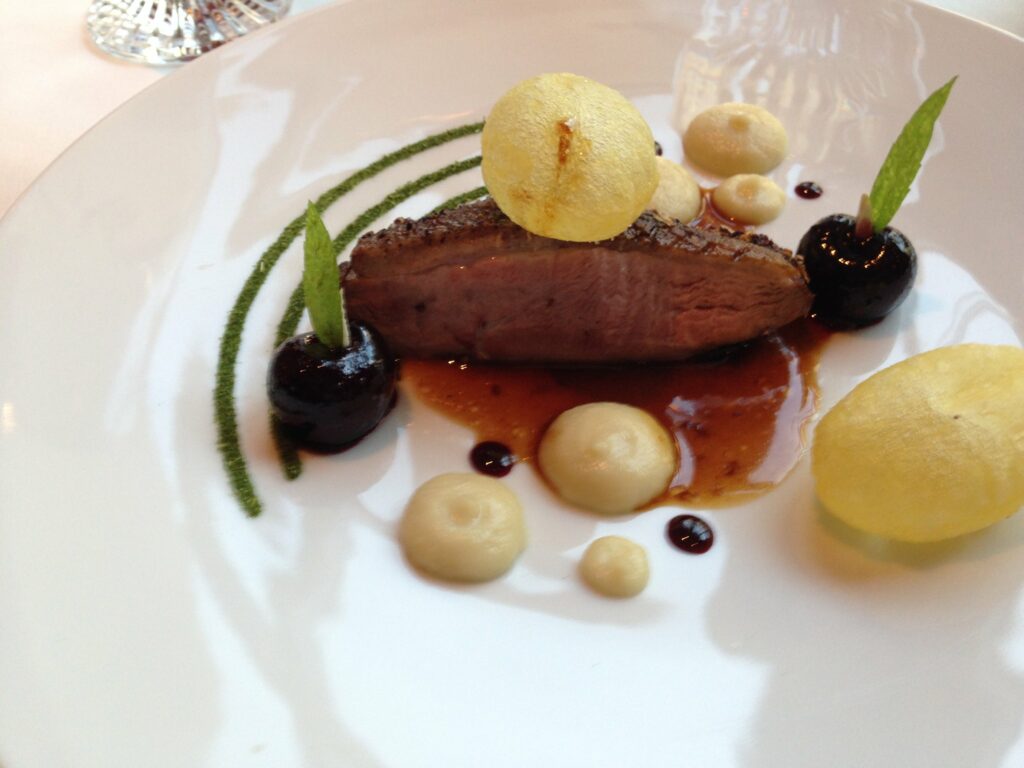

Main dishes usually follow a very classical concept. A piece of meat is subtly perfumed, accompanied by a purist vegetable condiment, a purée held together by a classical sauce (in Fréchon’s case usually royale, grand veneur, diable, poivrade, vin jaune or périgueux). A whole truffle cooked sous bois, sweetbread with licqorice and tobacco, duck with cherry and verbena, venison grand veneur or on the latest menu with a sauce poivrade. The venison was perfectly cooked, perfumed with épices douces and citrus powder, the poivrade was immensely complex with a pepper that shared the citrus flavours with the venison (Voatsiperifery?). The only slight let-down was that the celeriac-red beet-raspberry condiment remained a bit too long under the heating lamp. One of Fréchon’s signature dishes is a pigeon roasted on the carcass with pine and honey. It is the best pigeon dish I have ever eaten. The pigeon is, as ordered, perfectly saignant, the pine crumble on top adds a seductive crunch and some sweetness. Pearl onions filled with a celeriac purée and a bittersweet compote of fennel are the most harmonious partners possible. The acidity of a texture-wise very soft Xeres vinegar gel is certainly not for the faint-hearted but lifts the flavours and makes this dish appear polished, refined and elegant. A jus d’une diable is the icing on the cake. Peppery, acidulated, reductive, slight caramel notes, warm spices. As the langoustine-yuzu dish this pigeon à la diable is emblematic for Fréchon’s cuisine that can reach sky-high levels, create emotions, dishes that you will never forget.

The desserts of Laurent Jeannin have always been a high note. Jeannin was one of the best craftsmen in the pastry world. His technical brilliance and inventiveness are unparalleled. His creations had the unique signature of being feminine, volatile and perfumed. A lemon from Menton is a unique representative of the en vogue trompe-l’oeil dessert, not just because Jeannin was one of the first to cook such a dessert, but because he refused to create his lemon on a blown sugar sphere. Meringue is shaped with liquid nitrogen, resulting in a very soft and delicate “lemon” with a filling of pear with a touch of mint. The meringue is covered by a bright yellow jelly of limoncello resulting in a complex acidity. This dessert is so extremely perfumed that the flavours appear almost unreal, artificial but in the best way imaginable. Feminine was the word that came to my mind first both when tasting this course and a snowball of lychee with peach and eatable rose leaves. Jeannin’s talent to work with chocolate is equal. The holey Nyangbo chocolate sphere with a quenelle of red fruits, chocolat and tea completely covered in gold was dominated by a lovely jeu de textures, the flavours perfumed, bitter, fresh, opulent. Laurent Jeannin was a superb pastry chef, who passed away far too early, a pastry chef who belongs nowhere but in the heaven, the hall of fame of pâtissiers.

With Julien Alvarez, though, Fréchon appears to have found a worthy successor. A dessert of black truffle that I tasted on the first day they had it on the menu was a work of pure decadence. A sugar sphere filled with an emulsion and an ice cream of black truffle, covered with a black truffle dust resting on a sablé, surrounded by a crumble of cazettes spilled with an opulent Gianduja chocolate sauce was so good, it is hard to describe. The textural contrasts of the super-thin sugar sphere, the sablé and the cazettes each added a different kind of crispiness, while the emulsion with its foamy texture provided an almost volatile truffle aroma. This emulsion covered a far more intense truffle ice cream, thus the truffle flavour intensified until the heart and became more volatile till the end. Very poetic, is it not? The chocolate sauce was so creamy, thick, opulent and delicate resulting in a dessert that made you feel like eating the most flavourful sin created. Superb.

Epicure is a great restaurant – not just because of the food. The service brigade is exceptional, perfectly informed about the dishes, silent, efficient. Our sommelier knew all ten dish – ordered à la carte minutes before – by heart, thus was able to create an excellent pairing. They are très charmant and have this certain humour you only encounter in French restaurants.

Both bottle-wise from Burgundy to Bordeaux you will find anything (admittedly, the prices are not for the faint-hearted) – and glass-wise – Boulay, Gerin, Chapoutier – there are always very good open wines – Bernard Neveu and his lovely predecessor Marco Pelletier have created an impressive list.

Since Le Squer has gone into a modernist, Ducasse a naturalist, Alléno a molecular, Epicure is (together with L’Ambroisie and some others) one of the last strongholds of neo-nouvelle cuisine in Paris. Fréchon creates some of the most complex classical elixirs, he is one of last defenders of dishes that are emblematic such as his poularde en vessie, he is master of both cuisson and flavour-pairing. His dishes are accessible, harmonious, precise and elegant – so utterly French, so utterly delicate.

This report is so clear, limpide of truth and objectivity, long due to set a valid explanation of the culinary situation in France. Frechon is a rock and has done the perfect assimilation of the culinary evolution, sifting through good and bad, separating "Le bon grain de l’ivraie" into the core of France taste and gastronomical heaven.

Bravo for the report and bravo to Chef Frechon.