What France in the 1980s was and what Spain continues to be since the early 2000s is what Japan is today—a pre-eminent “go to” country for the inveterate gastronomic traveler. The participants are rich Chinese (especially from Hong Kong); well-to-do bloggers; entrepreneurs who board a plane to Tokyo whenever they wish; and chefs searching for new sources of inspiration. Eating alone is common, since the odds of obtaining a seat in the small, highly-desired restaurants is enhanced. Nearly all the activity takes place in Tokyo as it is the melting pot of nearly every kind of Japanese cuisine, unlike, for example, Osaka which is most noted for its proletarian food; Kyoto for kaiseki cuisine; or Fukuoka for Hakata ramen and seafood from the waters off Kyushu island. The entire country, however, is blessed for its rich and varied produce, too rich and varied to go into here. To partake of it in its full glory means exploring much of the country even if only by train and local taxis, which is what most visitors do. What you notice in watching the chaotic, unsightly, unplanned scene rolling past your Shinkansen window is that thrown in with the five-to-ten story apartment blocks; the landless single-family houses with brown tile roofs and a car port; the pachinko parlors and small industrial “ateliers” are small plots of land on which grow rice, vegetables or other produce. It’s no wonder, then, that the Japanese have a gastronomic landscape in the most far-reaching sense of the term.

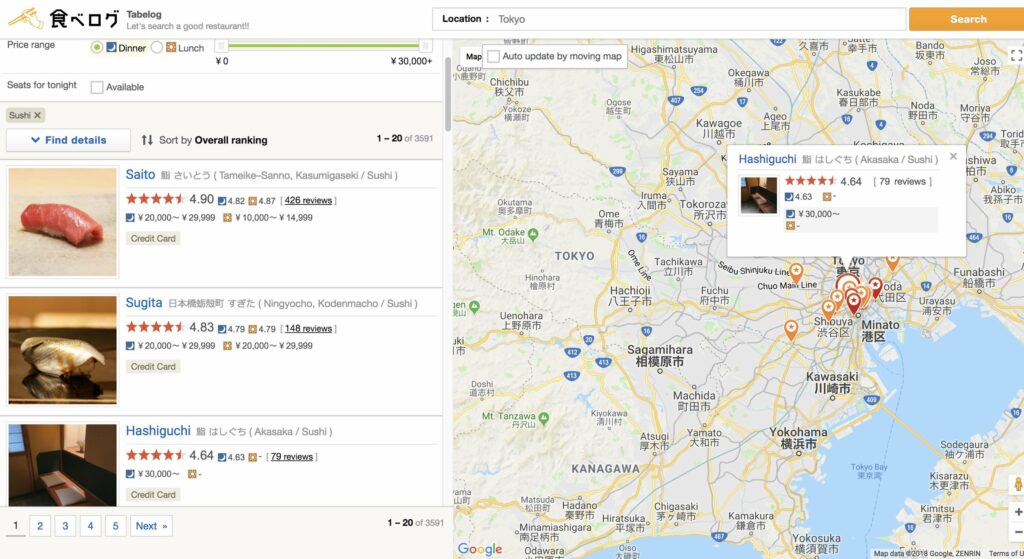

Scoring a seat at a high-profile Tokyo restaurant has a degree of difficulty akin to landing a quadruple axel. There are restaurants that are “invitation-only” and impossible to book unless you knew the right person. In my opinion, it’s not worth worrying about this because there are many emblematic restaurants that with advanced planning you can experience. Still, so many restaurants are bandboxes serving less than two dozen patrons a night, on top of which the ratings game has skewed and narrowed the playing field ever since the Michelin launched its Tokyo guide in 2007. If you go to a sushi bar, for example, with some Americans as your fellow diners, the establishment is highly likely to be in the Michelin Guide. Further complications evolve from the massive restaurant-goer database Tabelog (pronounced tobbelog) with its nearly 135,000 restaurants just in Tokyo, close to 9,500,000 “reviews” and a staggering number of diners’ photos, which I often use instead of the Michelin since diners consider Tabelog as more reliable. Because there are no formal inspectors with Tabelog, a restaurant can’t kick them out, thereby creating another group of virtually-impenetrable restaurants—those with very-high Tabelog ratings that are not in the Michelin Guide.

The best way to secure difficult or worthwhile reservations is to have a Japanese friend who would book for you under his name. If you tell him the dates of your stay, give him discretion to fill in the dates and the restaurants according to their availability. It’s not so much that restaurateurs are necessarily biased against Westerners, but being short-term visitors, gaijins are apt to cancel at the last minute, which is also why restaurants impose heavy cancellation fees up to the cost of the meal. Compounding the problem is that given the small number of customers they can seat, restaurants give priority to their regulars. Short of that, hope your hotel has a crackerjack, well-connected and persistent concierge service that has relationships with certain restaurants and might catch a cancellation for you. There are also reservation services to which you pay a booking fee, but having never used one, I can’t say how successful they are at getting you a place in your restaurants of choice as even they are limited in the number of bookings they can provide.

Among the Tokyo dining elite, sushi holds pride of place. In all my years of dining, I don’t recall a culinary category that has been as dissected, analyzed, or criticized in its minutiae, which may account for why reading blogs about sushi bite-by-bite can be tedious. Compared to a several-course Western meal that contains a myriad of ingredients, preparations and techniques, sushi is “simple”, or so you would think. But because of its directness and relative transparency, it creates its own type of hyper-analysis of the nigiri (the “piece” of sushi) among which are the size and selection of the pieces of fish (neta); the compactness of the rice (shari); the flavoring of the rice (the type of vinegar, whether sugar is added) and its intensity; the seasonings, such as wasabi or sweet soy sauce (nikiri); the temperature of the fish; the scoring, or knife cuts, on the fish; the relative size of the nigirias measured against the pantheon of itamae (sushi chefs); and, as you will read below, aging.

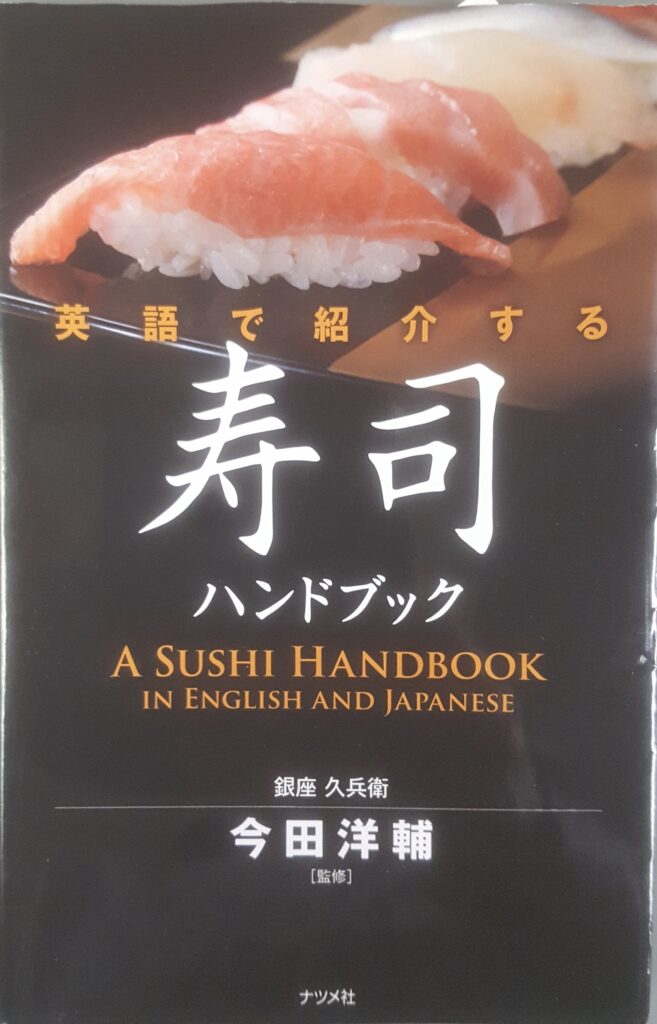

Unlike the not-too-distant past when ordering at a sushi bar was à la carte or choose your own from start to finish, omakase (chef’s choice) has made a virtually complete takeover. To my mind, it has taken away diner autonomy and some of the dialogue and informality between customer and itamae. There is often an assembly line or militaristic aspect to the experience as everyone is served the same course at the same time. So rigid has this become that a sushi bar I went to in Fukuoka called my hotel looking for me at exactly at 6:00 PM even though the three of us arrived at 6:08. (On one hand, showing up late is considered impolite. On the other, there’s about a 50-50 chance your taxi driver will make you late as he won’t be able to instantly find the restaurant’s entrance, thereby giving you the ever-ready excuse you need for being late even when it’s entirely your fault). The result is that the outgoingness of the chef is now a more significant element in the atmosphere of enjoyment along with how well you hit it off with him. In this regard, you don’t need to be knowledgeable, but rather to show keen interest by asking questions. My preferred approach is to play a guessing game by saying, for example, “Hokkaido?” when the chef serves you sea urchin, or “Kyushu?” when he serves you kohada (gizzard shad.) Even better for demonstrating your seriousness is arriving with a small book such as this one, which I took with me to one sushi shop where the chef smiled his approval.

My two favorite sushi visits were at Hashiguchi and Hashimoto. I was favorably predisposed to Hashiguchi because he doesn’t want to have anything to do with the Michelin people and doesn’t allow people to click away with their cellphones. That he works alone and serves but eight customers at a time also inures to his favor especially since eight seats just about guarantees intimacy and wa, or social harmony, whereas twelve lessens the odds. I also thought that Hashiguchi-san and I hit it off pretty well. since, as noted above, I expressed keen interest in the impeccable courses he served me, and going to far as to exhort me, in his limited, but hardly non-existent, English, to return in November or December during the peak bluefin tuna season.

Only at the bottom of the fourth page in the rank-order Tabelog Tokyo sushi restaurants do you presently find Sushi Hashimoto. It is likely because he is young and has had his own shop only since December 2014.

My guess is that he will be shooting up the ranks and that his eight-seat counter will become even more difficult to book. Among the sushi-ya we visited this trip, Hashimoto was my wife’s favorite and my co-favorite with Hashiguchi. Hashimoto excels in tsumami or the several small appetizers that precede the nigiri sushi. As a counterpoint to rigid omakase, tsumami is a singular, welcomed development in contemporary sushi restaurants. It brings the sushi chef into the realm of so-called creative chefs and adds variety to the meal. Hashmoto-san served everyone eight or so such dishes with his sardine and pickled radish wrapped in what you might call a skinny maki without rice being unforgettable; the same for a chawanmushi with an inspired addition of blue cheese. My wife, who generally isn’t an admirer of awabi (abalone) now found some she loved when she ate Hashimoto’s in liver sauce. By the end of the meal, the room took on what you could call a dinner-party-for-eight atmosphere with all the customers talking to each other, even in one instance exchanging cartes de visites—the ultimate expression of wa.

Until about a dozen years ago, I, like most, assumed that all fish tasted better the closer to the moment someone caught it. Only when I was having dinner one night at New York’s Sushi Yasuda, did Yoshi, my regular itamae, tell me that not all neta tastes best when just out of the water or even some days after. The incident stuck with me, and when I started reading about sushi-yas dedicated to aged fish, I decided to visit one. A leading one, Hatsunezushi, a 30-minute train ride outside of Tokyo, eluded me last year and turned out to be closed indefinitely this year due to the illness of the chef’s wife. With only a relative handful of sushi shops serving aged fish, I chose Sushi Inomata in Kawaguchi, its locale being an utterly charmless, hodge-podge Tokyo outlier about a half-hour train ride north from Tokyo Station. We thought it would be a good idea to ask a dear Japanese friend, also named Yoshi, to accompany us, the better for picking the brains of Inomata-san regarding aged sushi.

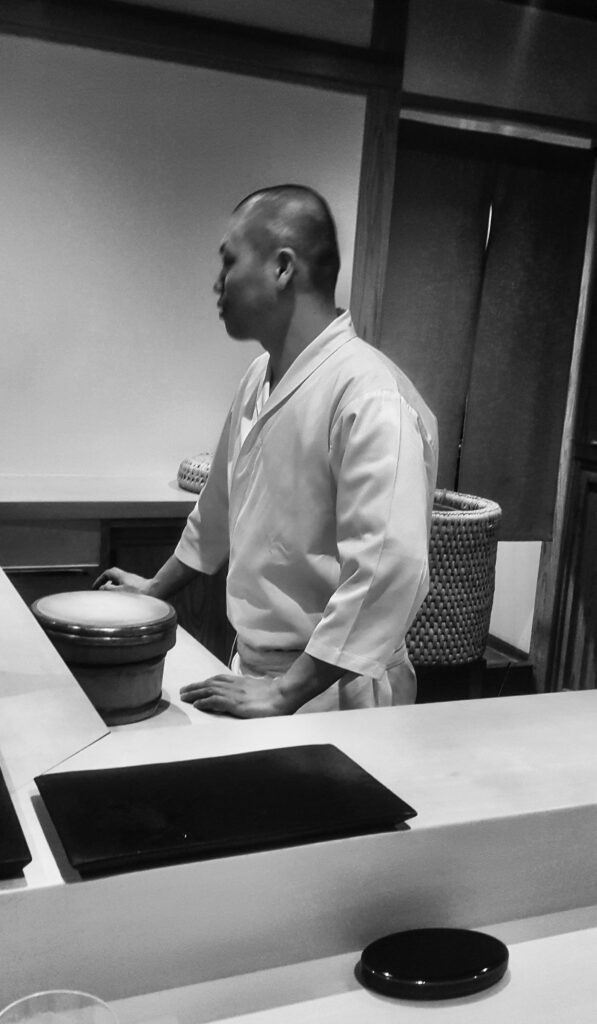

Situated on the ground floor of a small apartment house, Sushi Inomata is, beyond its eight-seat counter, spare and sparsely decorated. This lack of concern is underscored by two commercially-branded beverage refrigerators in a corner. But because Inomata’s wife is charming and hospitable, she makes the atmosphere warm and welcoming.

Young, stocky and rather taciturn, but clearly dedicated, Inomata-san works alone. Despite his reticence, he seemed happy to answer our questions, which were more than usual given our curiosity about aged sushi.

To age his fish, Inomata uses seaweed and miso and keeps the uncut fish in several refrigerators, all set to different temperatures. Kajiki (marlin) gets ten or more days of aging; tai (sea bream) is kept in the fridge for five days; chutoro, the medium-fatty tuna ages for five or six days; akami, the leaner, more red tuna stays in the fridge for four or five days, while the prized tuna from Omari on the northern tip of Honshu Inomata ages for ten days or more. Aji or horse mackerel that came from Izumi on Kyushu Island (top quality, according to Inomata) gets aged for two days (For more information on aged sushi, you can check The Sushi Geek).

Not everything Inomata served us was aged. Hamaguri, a springtime hard clam never served raw was cooked in sake. Shrimp, octopus and uni were others, while whale meat from Iceland (“Hard to get top quality”) occupied pride of place in the omakase, but to us the assertive taste made it something of an acquired taste.

The meal progressed from mild tasting to strong starting with chutoro and ending, before a shrimp and Chinese yam tamago, with the clam. Although the three of us are hardly sushi-dining neophytes, especially our friend Yoshi who is a food-loving Tokyoite, we felt that to fully appreciate the differences and nuances, we needed to taste fresh sushi side-by-side with aged, something that is highly impractical and improbable. Undoubtedly sushi addicts have conditioned their sense of taste (along with learning the myriad of nuances) to recognizing the subtleties of sushi, the same way that one does with wine. Another such fellow is my California-based social-media acquaintance Robert Driscoll who has been to Sushi Inomata and seemingly to every sushi shop of consequence in Tokyo. I asked him about differences between aged and fresh, to which he replied, “Once you gain sufficient experience having various fish with different aging times, you can usually guess the age within a day or two. As the fish is aged, the flesh becomes softer and more velvety; the color darkens and flavor/umami deepens and becomes more complex. An ikejimi shiromi (a white flesh fish such as sea bream, amber jack, flounder, and sea bass that is killed using the ikejimi method which paralyzes the fish and sends the blood to the gut cavity for richer color and flavor) can be very firm and chewy (almost crunchy) when very fresh. It is also very sweet and clean tasting, but it doesn’t have depth of flavor. That makes for great sashimi, but not necessarily great as neta for nigiri” if.e. the fish topping over sushi rice.

Next: A tough dining ticket in the countryside somewhat near Nagoya.

The mention of Sushi Yasuda brings back so many memories, as Yasuda-san himself was the one who taught me the most basic information about the art of nigiri making, fish aging, shari and so on, and his leaving NYC years ago prompted my trips to Japan in trying to relive this experience.

I find it extremely hard to pinpoint a list of my favorite sushi masters, as I feel like they all bring something different to the table (except for maybe Jiro-san’s rushed style). However, I have to agree with you full-heartedly that Hashiguchi (his ranking in Tabelog was lower when I visited, I am happy to see him rise up in the ranks) has always been a memorable favorite. He was particularly fond of shellfish in his omakase which was a refreshing change for us.

I have not tried the work of the other chefs you have mentioned, but after reading your article I am excited to do so. Next up for my sushi adventure is another visit to Amano-san at Tenzushi, whom I would call one of my favorite sushi masters of all times. Kyushu style sushi is prominently different than Edomae, but Amano-san recently started to combine these two methods in his omakase. How exciting!