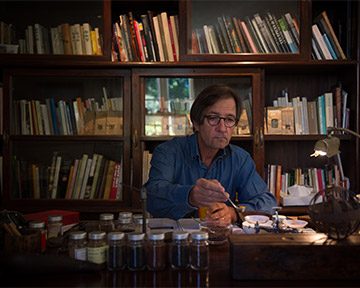

Over the past decade, Les Maisons de Bricourt (the Roellinger family’s nomenclature for their Cancalais empire), has changed considerably. Since closing his Michelin three-star restaurant ten years ago because of the chronic pain resulting from the nearly-fatal beating he endured when he was 21, Olivier Roellinger has devoted considerable time to building a remarkable retail spice business, Épices Roellinger, while continuing to expand his lodging and restauration facilities. What used to be his second restaurant the bistrot Le Coquillage is in the 1920’s Château Richeux in the neighboring town of Saint-Méloir-des-Ondes in which there are also several very comfortable hotel rooms.

Le Coquillage has among its offerings classics from the three-star Guide Michelin days along with new dishes created by Olivier’s son Hugo, who is now in charge of the kitchen, with his father looking in from time to time. Now Olivier spends a good part of his time traveling around the world visiting spice producers and being a consultant to many of the chefs in Relais & Châteaux properties in France.

Part of Roellinger’s hedonistic empire is spread around Cancale, the “Oyster Capital of France”, which with its Breton stone buildings is harmoniously preserved and little commercialized. In the center of town are his spice shop Épices Roellinger; the café-bakery Les Grains de Vanille; Le Corsair cooking school; a four-bedroom guest house; and five cottages by the sea.

In Saint Méloir-des-Ondes, La Ferme du Vent, a group of striking new buildings a short walk from Château Richeux, faces the sea with its five large luxurious bedrooms, beauty spa, Celtic bath, and a reflexologist, as well as a retail bread baking hut.

Mercifully, we would say, Le Coquillage is not on the turbocharged gastronauts’ bucket list. Besides the clients from outside the region, its patrons are the regional middle-class and retirees living nearby who are attracted by the gentle prices of food and wines and the value for the money, as well as a table here or there of anglophone tourists. Because the restaurant’s foundation rests on Olivier’s classics, this makes it a must-visit for those who seek a deep, sophisticated appreciation of the history of French gastronomy. It’s the opposite of many of the restaurants at which it has become so difficult to obtain a reservation. Unlike so many of these tasting-menu-only, “narrative driven” restaurants, Le Coquillage is not “one and done”. It is good for dinner-lunch-dinner or “three and out”, there being no repetition unless, of course, you have a dish so haunting that you must have it again, such as the Mystères du Tonkin “pho” or any of the St. Jacques dishes.

Robert Brown: Henrique, what were your general impressions of Le Coquillage’s cuisine?

Henrique Jayer: My two dinner visits to Le Coquillage were very favorable. The Brittany shellfish are evidently second-to-none in quality, the dish concepts sound, and the cooking mostly precise. That said, Le Coquillage is not a restaurant that envisions another chapter to Olivier’s cuisine. However, even resting on its laurels, Le Coquillage is still a better restaurant than a good number of significantly more expensive restaurants in newer markets and still a more satisfying seafood restaurant than you would find in those markets. I am quite positive it would put Noma to shame. The kitchen does not develop the cuisine for this season’s prepaid ticket holders but instead rehearses tried-and-true recipes. There are no plankton cakes for dessert; instead there is a magnificent dessert trolley.

At its best, I think of Roellinger’s legacy as the Baudelaire of French gastronomy. His shellfish are moored in Cancale, but his spice blends resonate with the expansiveness signified in the final stanza of the poet’s “Correspondences”:

Ayant l’expansion des choses infinies,

Comme l’ambre, le musc, le benjoin et l’encens,

Qui chantent les transports de l’esprit et des sens.

[Scents that] expand infinitely,

As incense, amber, benjamin and musk,

Which sing the transports of the mind and the senses.

Which is to say that I think Roellinger is successful in evoking faraway places through aroma and well-researched spice blends. But he manages to do it in a way that is still a lyrical expression of a single chef. Baudelaire was just such a poet, on the cusp between Romanticism and Mallarmé, or between a single voice and the effacement of the lyricist altogether. What do you think of the cuisine today?

RB: I adore the cuisine there. It reminds me of the best restaurant meals I have had on the Cóte d’Azur at the hands of Roger Vergé and Jacques Maximin to name just two; what I call “light and bright” cuisine. It must be because much of the cuisine there is seafood with the fragrance of herbs and spices. It would be interesting to be able to discern how much of the cuisine is Olivier’s and how much of it is the son’s, the latter in terms of executing Olivier’s cuisine and dishes that he, Hugo, conceives on his own. You and I have been in on-line discussions in which we lament that most chefs who follow in their father’s footsteps don’t seem as compelling. With Hugo, it is tough to discern if he has his own approach or is happy to carry on in his father’s vein. But if “Le grand Choix de la Baie” menu (I’ll get to the various menus in a bit) is mostly Hugo’s, then he has a way to go to catch up to his father. However, I am sure that the spirit of that restaurant and some of the dishes themselves are on-going, and I would urge anyone who takes dining seriously to visit. It is an easy and pleasant two-hour and twenty-minute train trip from Paris Montparnasse and then a short drive from the Saint-Malo station.

HJ: In a way, Le Coquillage seems hermetically sealed, preserved in a past when chefs sought out spice rapports that not only coalesce but synthesize and become something greater. Olivier anticipated the market driven trend of bringing spices into the repertoire of French technique, yet there are important differences, and they distinguish the repertoire at Le Coquillage from the mainly unfortunate fusion dishes that have proliferated around the globe. I think we can conceptualize fusion cuisine as formulated in a corporate boardroom, whereas Olivier’s dishes are works of inspiration. Today’s fusion dishes are somewhat of a default repertoire for anonymous restaurateurs: umami is a buzzword, baos a cliché. Le Coquillage is thus a great place to try auteurist fusion. The shellfish, and particularly the St. Jacques, are unequaled outside of Japan. They are never pan-seared and the cuisson is always perfect.

RB: While we are on the subject of shellfish, since Cancale is famous for oysters, how did you find them there? I thought they were better in February than in October and that the best, if not the only, place to have them was at Le Coquillage. This recent October was different. The flat wild ones I had in a restaurant along the port were the best this time. Too bad we were both thwarted in our hopes to have the giant pieds de cheval oysters that weigh a couple of pounds or so. The end-of-year season is, of course, very short and the divers have to have a license to retrieve them.

HJ: Yes, I did taste the raw oysters; each was dotted with a different spice. In addition, I tasted his wood-fire grilled oysters with an emulsion. A visit to Cancale should include indulging, and I tasted raw ones at the Breizh Café that the great Parisian food writer Sophie Brissaud recommended to me, which is a seaside spot that specializes in excellent buckwheat galettes and wheat-flour crêpes which you can wash down with good Normandy cider.

Back to Roellinger, I want to mention the spice blends and their organic rapport with the Brittany shellfish. For the moment, let’s set aside for the moment the history that brought spices to Saint-Malo. Olivier’s spice blends may at times approximate a foreign profile, such as when mustard seeds are redolent of wasabi on the St. Jacques with red beets. It was uncanny because it was not a wasabi imitation, but was very close to approximating the texture and piquancy of the rhizome paste without actually attempting to simulate it transparently. The distinction I would make is that Olivier instinctively seeks out correspondences rather than engineers simulacra. That is why I refer to Roellinger as the “Baudelaire of Haute Gastronomy”. He manages to transport you to a foreign place through his spice blends while not quite veering over into pastiche. He still believes in metaphor, or correspondences, like a lyric poet does and has not succumbed to pure imitation, as when laboratory chefs engineer fake olives or produce other simulacra.

A good illustration of Olivier’s evocation of metaphor is his “Mystères du Tonkin”, a Vietnamese-inspired masterpiece from the Maison de Bricourt days that adds a fragrant bouillon of young vegetables and seafood to some raw langoustines, clams, tiny sea snails and squid noodles. Hugo is doing a masterful job preparing the bouillons. I joked that this dish is the essence of Vietnam and that nowhere in the country itself could you taste a more complete impression as you can in this dish. I stand by that claim. By not simulating pho precisely, there is a distancing to it that makes you objectify it and recognize it in its similarity and differences. That is the essence of metaphor, a transport from one object of comparison to another. Roellinger smartly does not try to recreate pho (How could he, without the indigenous citrus and fresh herbs of Vietnam?) but manages to enhance the pristine shellfish. I would say that is the reason Roellinger’s spices work in an organic way, because the sweetness of pristine St. Jacques, palourdes, and homard bleu is elicited uniquely by spices. (Not incidentally, the Breton Bernard Pacaud’s best lobster dish at L’Ambroisie is his “diavolo” bisque with piment d’espelette in autumn, and his langoustine masterpiece features that diabolically good curry sauce).

RB: What would you choose from the wine list to pair with the cuisine? I noted some good values in white Burgundy, which possess a citrus/iodine/yeastiness, that would be my choice.

HJ: Yes, the cuisine nicely complements white Burgundy, and the spice profiles are elegant and do not outvoice the wine. Actually, coming from the United States, I was pleasantly surprised at how austere the dishes were, eschewing overtness for minerality. You will want to veer towards a Raveneau or Dauvissat to pair with the menu rather than with an opulent Coche-Dury or concentrated Roulot if you are choosing a bottle or two to accompany the full trajectory of the meal. In the tasting/half-portion menu of classics from the former Maison de Bricourt , there is a dish, Langoustines translucides–Reves de Cochon et Sauge Ananas de la Serre”, that reminded me of Manresa’s tidal pool, but more saline and mineral than even chef David Kinch’s masterpiece. It was slightly larger in portion than the recent chi-chi portion/plating in Kinch’s and showcased the shrimp and shellfish better. Kinch’s plays a bit more on an umami-saline balance. Next was an avocado mousse with Breton sea urchins, a familiar-enough combination. Christian Le Squer concocted a better version in his Paris Ledoyen days, but the austerity of Roellinger’s was surprising in that you would never find such restraint in a restaurant receiving mainly international diners. I would like to ask you to discuss the tasting menu format that you uncharacteristically esteemed before I discuss in more detail the St. Jacques preparations and the two lobster dishes.

RB: The half-portion Roellinger/Maison de Bricourt classics menu “Au gré du vent et de la lune” offers a selection of dishes that are readily divisible by two such as three oysters instead of six; half of a lobster from cutting a whole one down the middle; half of a fish filet, and so forth. You also find one or two classic Roellinger dishes on the prix-fixe à la carte menu “Le grand choix de la baie” and the no-choice surprise menu “Un grignotage au bord de mer”, but on my last visit I found the half-portion carte to be more satisfying than the “Grand choix de la baie”, although the staff is real easygoing and you can play around with just about everything from the kitchen except the fourth offering, which is a plateau de fruits de mer that you have to order in advance, and which I didn’t find any better than other luxe ones I have had in Paris cafés and brasseries.

For me, though, the “Au gré du vent et de la lune” menu is only “tasting menu–ish”. The main point is that Roellinger created these dishes as full-portion ones. The worst aspect of the generic tasting menu is that the chef creates them to fit a small-portion format (or as the French put it best, a “formule”) which is like making dishes with one hand tied behind your back. It usually means no whole fish; no skin and bones; nothing requiring being a bit adroit with a knife; and, unlike Le Coquillage, not all the parts of a lobster. I never saw a whole-fish dish from Roellinger, so I would be curious to know if he used to offer them or if the kitchen would make one for you now. Still, the dishes of yore he offers today have a grandeur you will almost never find on any other chef’s tasting menu. What really raises my hackles (just to go a little off-topic) are “small dishes for sharing”. Now there is fine dining’s leading oxymoron, with an emphasis on the “moron”.

HJ: I share your disdain of the small plates phenomenon, and you have seized on an important distinction in that in tasting menu dishes outside of Japan, the pottery and visual aspects are aimed at predisposing you towards the dish; the taste is a kind of poetic conceit, like a literary sonnet. Its aim is to surprise you in a somewhat facile way. A great dish at L’Ambroisie is like an epic poem or modernist novel that unfurls in all its details and gives you time to ruminate and discuss. With the exception of caviar or uni, it is tough to create a small dish that respects an ingredient. Or to take an example relevant to a seafood temple, a whole-fish dish has many textures and tastes, and that there are none to be had at Roellinger today is disappointing for a restaurant of this pedigree. There is a tasting menu, à la carte, and a platter menu “Le grignotage des bords de mer”, which actually features prepared dishes and is not the brasserie type of fresh shellfish and crustaceans. This latter menu was well-orchestrated in the opening raw and barely cooked shellfish but showed the format’s limitations in that once the warm preparations began, the fish were still cooking in their casseroles. This is not a precise way of serving cooked fish but typifies the rusticity of Le Coquillage. I’m glad you have pointed out that the tasting-menu portions are mainly more substantive than a Thomas Keller-inspired format of making you pine for ten more bites, and it was a nice feeling to have escaped to portion civilization. The St. Jacques dishes were satisfying in that they featured several slices of noix to accommodate the cold and warm preparations. The most memorable of these cold preparations featured red beets and the mustard seed “wasabi paste”, while another one lifted the flavors of the excellent St. Jacques with the acidity/aromatics of agrumes. The mackerel was equally impressive, as was crab in a sea urchin sauce. A daurade tartare was very precisely seasoned with spices, but it is not really on the level of Gêrald Passedat’s version with bottarga, caviar and a cauliflower nage that he serves in Marseilles. The lobster dishes, both the spiced and à la Cancalaise were disappointing, as the serving size was paltry with the curry version while the chimney one tasted reheated. Hugo is using the claw and some other meat for the spiced version while he reserves the split carapace/tail for the Cancalaise one. The spices worked well enough, but this is not in the league with a haute gastronomie dish such as Mikael Jonsson’s lobster with coral emulsion, which is more precise, or Bernard Pacaud’s lobster dishes that form a synthesis with Noirmoutier new potatoes; or Alain Passard’s rustic masterpiece served in aiguillettes with the tomalley.

RB: Let’s talk a bit about the feeling of the place and the service. As I have mentioned previously, the whole Maisons de Bricourt operation is understated and welcoming.

HJ: Yes. I found the reception room charming, and pretty bereft of Seafaring kitsch, and the service refreshing in that they are both pretty much without affectation. They are clearly not geared to gastrotourists, as the front of the house does not wear painted smiles. With some of them, you have to work to earn smiles. There is an intermittency to their appearance–feminine severity followed by sweetness, which is an intoxicating witches brew, to cite Nietzsche. In all seriousness, they are accommodating in letting you compose your own menu, as you noted.

RB: I have a weakness for sprightly, vivacious servers such as our favorite sommelière Anaïs at L’Arpège. During my first visit to Roellinger, there was a woman in charge of the dining room named Valentina. You could joke around and kibitz with her. Between my visits, she had a baby, so I did not get to see her this last time as she was only working a few lunches a week. This time the rest of the dining room crew made no impression, which is not to say the service is lackluster, uninformed or amateurish because it isn’t. It seemed to me that there are not trade-school-trained servers because Le Coquillage is not a grand restaurant. In fact, Roellinger hires many local people. But to get back to the cuisine, I should take note that virtually all the seafood comes from outside the front door just like at Elkano in Getaria, and da Maria in Fano on the Adriatic in Le Marche. But then there is this seeming contradiction of the spices coming from thousands of miles away. Roellinger, however, justifies it in an interesting way by saying that the corsairs sailing from Saint-Malo, whose job it was to plunder enemy ships from the Middle Ages to the early 19th-century brought back large quantities of spices to Brittany.

As an old school, old hand gastronome, what I admire most about Olivier is that he does not, and never did, play “the game”. Remarkably, he took up cooking after his horrendous beating and five years later opened his restaurant as an autodidact. He subsequently reinvented himself, gave back his Michelin stars, and built this rather expansive empire that oozes with integrity and consideration. Of course, as much as anything, I enjoy the hedonism of Roellinger’s Cancale. There has been a marked deceleration in the creation of full service haute gastronomie hotel-restaurants, many of which were built between the 1970s to the early 2000s. True, the facilities are spread out, but you can spend money in lots of ways—buy spices in what must now be the best spice shop there is; take a cooking class; have your feet massaged and manipulated in the hope of fixing what ails you; have a coffee and pastry in town at Les Grains de Vanille and so on.

HJ: I agree that Olivier’s unaffected comportment towards the industry is refreshing. Le Coquillage is not a restaurant that attempts to solicit diners, and in fact, may appear indifferent. This is a rare case where the “figure” of the chef is probably not a PR fabrication. When I watch Roellinger’s episode in the “Invention de la Cuisine” series, I find the portrayal earnest in a surprising way. He eschews marketing himself or his products according to the expediency available to him, such as the “free trade” tag for his spice blends. He could avail himself of that tag but chooses not to. Meanwhile José Andres and David Chang harness their benign stance against Donald Trump as if it were some radical gesture when it is a facile way to monetize their commodified empires. So I admire Roellinger, as I do his refusal to, for instance, open a seafood restaurant in Japan, precisely because he believes in a sense of place. What would it be like to eat Hokkaido scallops with the spice blends? Well, it would not be historically rooted as it is in Cancale, and though Bras and Gagnaire may be fine with seeing their visions extricated from the terroir in which they were born, Roellinger rightly poses the converse question: how would the Japanese tea ceremony ( 茶道 ) integrate in Cancale? Denaturing the context of dining may be lucrative, but it never creates a truly compelling experience. Even great sushi outside of Japan is compromised by the atmosphere, the uncertain rapport between the itamae and his guests, caused by the linguistic and cultural barriers. Language and culture are inextricably bound in an ineffable way.

In sum, Roellinger recognizes what you and I know, and observant diners do intuitively: that though capitalist globalization may work through a logic of expansion and denaturing the singular, the terroir-specific, it cannot succeed in evoking the essence of a place.

RB: I feel that in today’s gastronomic world, where the most famous restaurant opens an outpost in Hong Kong and Japan-Spain collaborations receive sponsoring and a social media blitz, the essence of a place is being eradicated in a significant way.

HJ: Agreed. Outposts, even at their best, still recreate brand icons that appeal to a broad and less acutely perceptive demographic. For most aesthetically attuned diners, this has little draw. It is akin to how the young Marcel of Proust’s “La Recherche” is obsessed with seeing the actress La Berma in her most quintessential role–nothing less would do–or of experiencing the flowers and people of a region in the most authentic way, rooted in their place. Despite the market’s attempt to condition us otherwise, you and I have thankfully not shaken the desire to devour the essence of a place. While the cuisine at Le Coquillage is very good, I think the most admirable quality of the restaurant is its preservation of Olivier’s style, and that is rooted in Brittany. Saint-Malo’s history of spices, which narrates a “globalization” before contemporary capitalism, is an integral piece to the puzzle. So, the preservation of both time and place–Brittany’s history and essence–that is an admirable achievement. It was a true pleasure to dine at Le Coquillage, and equally to discuss it with you, Robert.

RB: Indeed, this inaugural conversation between two gastronomy enthusiasts is auspicious if I do not say myself. We both are seeking the same conviviality in dining, both seeking the past in the present. Speaking of conviviality, it would be remiss to neglect the magnanimity displayed in Roellinger’s dessert trolley.

HJ: Yes, all of the classic desserts were of high quality, especially the Madagascar vanilla millefeuille, all of which you can sample at will. There are a couple light fruit-based desserts as well. I did not inquire, but I would love to finish the meal with a Calvados (what else!) from neighboring Normandy in the adjacent lounge. And any trip to Brittany needs to include a scenic drive culminating in a Kouign Amann in Baye at Frédéric Jegou’s boulangerie or La Petite Boulangerie in Riec-sur-Balon.

RB: Or not as far afield, sitting along the peaceful, bucolic River Rance at the Port of Dinan eating the one from Tatie Jeanne.

HJ: Brittany is both a verdant landscape with some breathtaking skies and a seafood lover’s paradise.