When I reflect on the greatest meals of my life, they nearly all took place during the heyday of La Nouvelle Cuisine Francaise, which flourished from the late 1960s to the mid-1990s. Life in the better restaurants revolved around the reflexive verb “se régaler” or to regale yourself. The convives in these restaurants in France seemed to have been more animated and at ease than those I have witnessed in the exalted “World’s 50 Best, everybody-having-the-same-meal” establishments of today. I chalk this up to two reasons. First, you are more apt to feel content and proud of yourself if you ferret out and cobble together an enjoyable, if not perfect, meal from a large array of dishes which you then share with your tablemates who ordered something different than you. Second, the people who waited on you were mostly in the background as opposed to being in your face and interrupting your conversations every five minutes or replacing one small dish with another. If there was one fault at my preferred establishments, it is that the chefs gave you too much food. Nevertheless, the chefs made their dishes according to where their creative juices led them, and they did it on a grand scale since, I imagine, they were taught to think big.

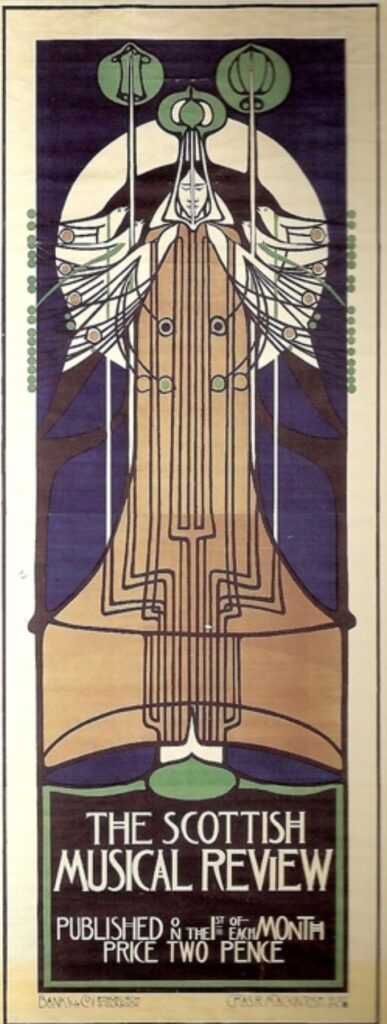

In recently planning the most rigorous European dining trip since going back to living full-time in the States, my goal was to find out to what extent I would be able to dine for two weeks in London, Glasgow, Paris and Cancale by returning as much as possible to my formative dining roots; in other words, going home again, gastronomically-speaking. Accomplishing the goal meant doing away with tasting-menu-only restaurants and fixed three-or-four course meals such as those belonging to the class of bistronomy restaurants. (As an accommodation to others, we did have in Paris a pleasant four-course, no-choice lunch at the newish Japanese-owned Montée and the obligatory menu surprise at the Michelin three-star restaurant L’Astrance). The goal of the trip also included returning to three old favorites: L’Arpège and Le Récamier in Paris and Le Coquillage, the Olivier Roellinger restaurant in Cancale, the Breton town famous for oysters; and first-time visits to the Ritz and St. John in London; Arnaud Nicolas in Paris; and three traditional restaurants in Glasgow where our raison d’être for going to the Scottish city was to pay a long-overdue homage to the father of modern design Charles Rennie Mackintosh.

I wonder how many others share my passion for ornate, historic dining rooms such as the Louis XV in Monaco, Le Cinq at the Hotel Georges V in Paris, and the latest one for me, the border-line over-the-top Louis XVI interior of the Ritz Hotel Restaurant in London. For “Puttin’ on the Ritz” add tuxedoed, professionally-trained waiters; beautiful table settings and serving implements; dishes carved and prepared in front of you; and what must be unique in the world of dining, live music from a pianist, female vocalist and a string trio performing nothing but classic popular music of the 1930s from the mythic, intangible Great American Songbook. Regardless of how many more people who love all of this, would they, as I did (perhaps egged-on by our bottle of 2008 Domaine de Vieux-Telegraphe from a monumental cellar deep in Champagne and Bordeaux) would have had to wipe away more than a few tears from the coming-together of so much of what I love in life.

My dining priority for what would only be two nights in London was to dine on grouse. After polling several gastronomes on social media, I made the fortunate choice of the Ritz. I could not have been happier. The grouse was cooked to perfection and carved in front of us. The game chips and peas and carrots very much enhanced the dish. The more-personal talents of chef John Williams were evidence in our starters of agnolotti in caramelized onions and a langoustine with fennel, verbena and beans. That they were à la carte dishes served in tasting-menu portions was the only false note of the evening. Being devotees of time-tested dishes rarely-encountered, we ended the meal with baked Alaska. We were transfixed the whole seven minutes or so it took our waiter to make it.

Having had a friend who often visited the late Brian Henderson, the well-known architect whose firm designed Gatwick Airport, we would hear about the gastronomic activities of Brian’s son Fergus before he started St. John. As a result, it has been on our desiderata list since it opened. Now I was able to make my maiden voyage, stopping on the way to St. John to see the Seattle-based artist TJ Wilson’s revealing and engaging documentary appropriately named “Fergus” at the art gallery Sadie Coles HQ. The restaurant did not disappoint me either. The design, executed by Henderson and his restaurant-development partner Trevor Gulliver, of white-tile walls evoking a butcher shop; the hanging lamps; and the simple chairs and table created a tasteful informality with no pretense at all in any aspect. Were I living in London, I would be stopping by every two weeks or so to indulge in Fergus’s enormous repertoire. Unpretentious as well is the food. My Gastromondiale colleague Besim Hatinoglu won the best-ordering contest with his rabbit in mustard. Still, I enjoyed a rich lamb broth and my slice of Middlewhite pork. The only dissonant note was a somewhat tough piece of wild duck. My chocolate ice cream was dense and rich, as enjoyable as any serving of gelato I have had in Italy.

Very recently when lying in bed greeting the new day, my refreshed, uncluttered head came up with the concept of what I call “Culinary Sanctuary Cities”, which I now use to describe those that remain steadfast in their gastronomic traditions. It is a condition that makes them all but impervious to the recent novelties of tasting-menu-only restaurants and avant-garde or molecular-gastronomy. Florence and Venice immediately came to mind, as did Lyon. To this I add Glasgow. I doubt there are any among us who go there primarily for restaurant-going. Mostly it’s a jumping-off point to the scenic islands and lakes and near-by Edinburgh. The one reason to spend time in Glasgow is to see some of the achievements of the immortal Charles Rennie Mackintosh, which are scattered throughout the city and most vividly an hour’s train ride to Helensburgh to visit the Hill House, a private residence that Mackintosh designed and furnished between 1902 and 1904 for children’s book publisher Walter Birdy.

I arrived in Glasgow without meaningful gastronomic expectations, but then leaving with indelible memories. I experienced the fact that there is a lot more to the cuisine than smoked salmon, such as oysters, prawns, scallops, mussels, crab, haddock, herring, squid and more. Even so, I wolfed down all the silky smoked salmon I wanted at the breakfast buffet at my hotel, the Dakota Deluxe, and at my very good breakfast at Café Gandolfi where my wife and I chatted at length with the owner Seumas MacInnes. As he had served on the board of the Glasgow Modern Art Gallery, we talked about early 20th-century in Glasgow and, of course, Mackintosh. We later had dinner at his restaurant next door Gandolfi Fish where the rich seafood larder of Scotland was on offer. We sampled Cumbrae oysters, langoustines, and a deeply-satisfying fish and shellfish curry. Our other two dinners at Rogano and the Ubiquitous Chip introduced us respectively to Cullen Skink, a rich and varied seafood chowder and venison haggis, the lightness and profound taste of which caught me completely off-guard. It certainly was like a bolt of the blue and ranks as close to the best dish of the trip, which, considering what was to lie ahead, is saying an awful lot.

Had I never been to Paris and were to arrive there on a flight from Glasgow, culture shock would likely be the operative phrase. Glasgow seems much smaller, although its population is more than half of that of Paris. Paris is the City of Lights where Glasgow is on the dark side. Glasgow is insular and homogeneous, yet despite its provincialism, I liked its unspoiledness, physical homogeneity and lack of pretense that spilled over into its dining establishments.

A restaurant like L’Astrance in the Paris’s 16th arrondissement could not possibly exist in Glasgow regardless of the type of cuisine. I am not referring necessarily to Pascal Barbot’s cooking, which, despite it “petiteness” and fussiness can rise to a high level. My wife did not really agree with me when I called L’Astrance with its menu surprise a restaurant for beginners. Yet, that is the way they treat their clientele by putting them in to a culinary straitjacket. But perhaps many of the people who go there are beginners as, so far as we could tell, we were the only ones who ordered a bottle of wine instead of their wine-pairing of humble wines. Because we wanted a bottle that would see us through the meal, we asked our young waiter to please tell us the dishes so that we could choose the appropriate bottle. He refused us, claiming that even he did not know what Barbot was preparing, which very well may have been true as it appeared that not everyone was receiving the same dishes.

Although Barbot is best-know for preparing vegetables, I found that the two meat dishes came out the best. A thinly-sliced dish of pork belly and a portion of wild duck were fine examples of what tasted to me were prime material. Yet, the shrimps were from Madagascar which, a friend told me, are what you find in supermarkets.

I suppose it is worth something that this visit to L’Astrance was the most satisfactory of our three without the travesty of a wine pairing my host requested the first time when the restaurant was new, and having on the second visit the kitchen run out of a dish we requested at the start of the meal, followed by having Barbot’s partner Christoph Rohat whisk away our bottle of wine before we had finished it, and summarily removing one of the desserts he had brought to our table.

L’Astrance is the least-expensive of Paris’s top-rated restaurant. It is intimate (small, in other words) and manages to attract many who want a restaurant that holds their hand or are in search of bragging rights. Yet like all several-or-many-course tasting menu establishments, it is all but impossible to have a perfect meal there.

What is interesting about Pascal Barbot is that he received much of his training at Alain Passard’s restaurant L’Arpège, which I have known since 1986, the year it opened. I check back from time to time because it is now my preferred restaurant in Paris, if not in France. Like L’Astrance, the main dining room is small and intimate. There is a private dining room in the basement and, which I never knew before, a chef’s table down the block where a waiter brought us as Passard wanted to have a farewell chat. It was here that he told us he “loved his profession”, which extends to his lively presence during part of the meal service complementing clients on what color they are wearing. Pity the waiters, though, as the kitchen is down a flight of stairs from the main dining room.

Passard offers generosity, but at a hefty price. Most ordered the tasting menu that relatively speaking offers generous portions. We, however, went à la carte as is our custom, and also doing some retro-ordering. A mustard gazpacho with celery sorbet was an old friend, a “be-sure-not-to-miss” dish. With its warm and cold and opposing textures, the dish is about at the top of Passard’s canon. For the third or fourth time, we ordered arguably his greatest dish, which he created in 1996, the homard au vin jaune. A server paraded before us an uncommonly-large, already-cooked Breton lobster. The lobster was sliced lengthwise into quarters to preserve the tomalley and cooked in a yellow wine of the Jura. It brings to mind the late Roger Vergé’s sensational lobster in Sauternes, but less sweet.

Our other main course, sweetbreads from Correze with sliced chestnuts and autumn root vegetables did not quite reach the heights of our lobster, but was a reminder of how rare it is to find sweetbreads as rich and dense as the ones you find in good restaurants in France.

My wife’s first course of fines raviolis potagères multicolorés is a dish that a friend describes as reconceiving “a Japanese dashi with the umami of tomato, in place of katsuo, and the tannic structure of verbena, in place of kombu…”

With its intimacy and informality from the closeness of the tables, I was able, without getting up, to lean over and say to a woman dining alone to make sure to have Passard’s unforgettable instant-classic dessert tarte aux pommes bouquet de roses made with three varieties of apples, which is covered with apple peels formed into roses. The dessert is now ubiquitous in domestic kitchens across France and sold in the market of Passard’s hometown of La Guerche de Bretagne, southeast of Rennes, as a means to help the local economy, and for which he helped invent a machine that mass-produces the apple-peel roses.

Le cuisinier Alain Passard, originaire de La Guerche-de-Bretagne en Ille-et-Vilaine, a lancé officiellement la tarte “Bouquet de roses” jeudi 19 septembre 2013. Le dessert va être produit dans les ateliers guerchais de l’usine Traiteurs de Paris. © Ateliers Vertigo

Le Récamier, which is on no one’s “must” list was, in the 1980s, a favorite of mine. The owner-chef Gérard Idoux is still in the now-much-diminished kitchen that unlike 20 years ago emphasizes perfectly-made and delicious savory and sweet soufflés as attested to by my wife’s cheese one and our Grand Marnier. As I always used to do, I ordered the kidneys in mustard sauce, a dish becoming increasingly difficult to find It was as great as I remember, and is one Idoux learned at the hands of his master the great Jean Ducloux, owner-chef of the legendary Restaurant Gruze in the Burgundian town of Tournus. I found no difference between them. With Le Récamier’s plant-sheltered terrace and location on a short, charming dead-end street off of Rue de Sevres, you almost feel that you are somewhere in La France profonde.

I never realized that there was a Meilleur Ouvrier de France category for charcuterie until Manresa’s David Kinch suggested that I visit Restaurant Arnaud Nicholas, a spare, but tastefully-designed bistro and boutique located in the 7th arrondissement between Invalides and the Eiffel Tower. As might be expected, the best part of our dinner was a selection of charcuterie such as pâtê en croûte de volaille et foie gras de canard; foie gras de canard au vin rouge; and a pâté en croûte Richelieu made with pistachios and a mousse de volaille at its center. This array of charcuterie seemed to the four of us to be as good as you are apt to encounter. The two main courses we shared was a hit and a miss situation. A chicken pie for two with vin jaune, cabbage and foie de volaille was heavy-handed and seemingly undercooked. On the other hand, the quenelles de brochet, sauce Nantua was delicate and ethereal, unlike any I have had back home, be it that dish or “your grandmother’s gefilte fish”.

(My colleague Brandon Garnier and I will be discussing on this site Olivier Roellinger’s Cancale after Brandon’s visit in early January. This is a remarkable place to spend two or three days for reasons we will chat about.)

What then to surmise from this trip? To answer my own question, it is that tried and true restaurant dining is far from being ancient history. It is quasi-ubiquitous, struggling a bit to survive, but readily-attainable with research, if even in a condensed form. At the high-end, one wonders what will be after middle-age chefs such as Alain Passard, Bernard Pacaud, Jacques Chibois, and Guy Savoy are no longer on the scene, or if the dining rooms of the classic luxury hotels such as the Ritz in London and Paris or the Hotel de Paris/Restaurant Le Louis XV decide to join the 21st century. Will there be more young chefs like Daniel Rose who have an affinity for tradition and history? All a traditionalist can say now is “Get it while the gettings (still) good”.