One of the first things that I do when I return to my family home in Athens is go downstairs to the basement where we keep our wine. That’s first and foremost for practical reasons because wine is in order at my family’s reunion dinners. I have many memories of going downstairs with my father to pick out the wine, and since he died, this ritual has acquired a new status, something that is to be exercised with the reverence for what we did before. But I also go down to the wine room because I simply like to look at the wine. I only spend a few weeks a year in Athens, so I never quite remember what the stock consists of. Thus, it’s always a wonderful surprise to discover an old vintage I had forgotten about, and to anticipate drinking it sometime soon. Our basement is not quite a cellar, but it’s the closest we have to one. It’s dark and a little bit humid and the coolest part of the house throughout the year. Most bottles rest on their side on narrow shelves in a pantry-like room alongside bottles of olive oil my grandmother acquires from a source she trusts along with home-made marmalade; oversize cooking utensils; and often some tomatoes. There are three generations of wine, as it were, resting there–some quite old bottles, from my grandfather’s time; increasingly fewer bottles from the 1990s and early 2000s acquired by or gifted to my father;, and a majority of more recent vintages that I have purchased, many of which have found their way into a small wine fridge.

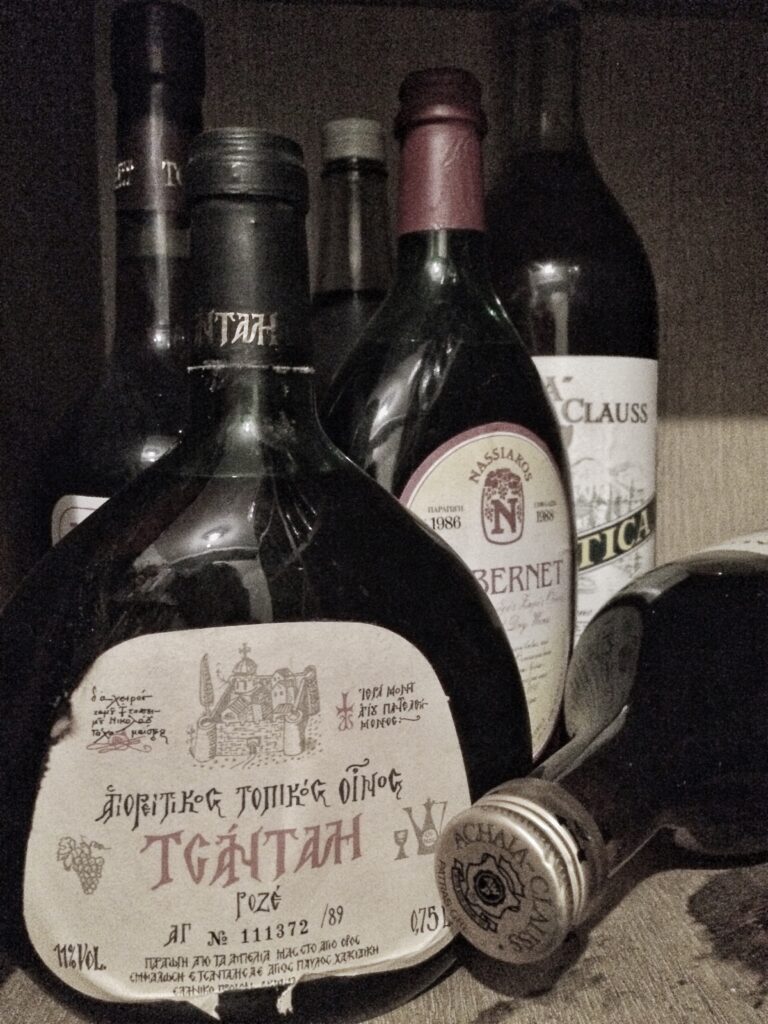

When going through some of the older bottles a few months ago, it occurred to me that this modest household cellar is a small testament to the progress that Greek wine has made over the past 40 or so years. The oldest bottles, those of my grandfather, are from the 1980s. They are composed mainly of the traditional wines of the post-war era: old school Retsina by Boutaris in a 3-litre bottle; sweet red wine from Mount Athos in a peculiarly shaped bottle to fit this wine-oddity; and sweet red Mavrodafni, by iconic producer Achaia Claus. There are also a few dry white wines from the same producer, among them the most famous label of the time “Demestica”. These are wines from a different era of Greek viticulture and wine making–what to me seems like the rustic and traditional wines of the past, though I suspect some of them were the early attempts at industrially-produced wine for the masses. I haven’t attempted to open and try any of them, as they are almost certainly long past their drinking stage. This way they also keep some life in them, making them the live fossils they are. The next lot of wines from the 1990s and early 2000s already demonstrates a quantum leap in quality, as well as focus. The bottles are a mixture of both more-traditional wines, like sweet Muscat wine from the island of Samos; a handful of Xinomavro wines; the northern grape variety of Naoussa and Amyntaion; and quite a few wines made from European grape varieties such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Syrah. Most of those wines, to my pleasant surprise, are drinking pretty well, with the Samos sweet wine seemingly intact despite the conditions that it has been kept in not being ideal. This might be an oversimplification, but in my mind these bottles represent the trend of Greek wine making during the 1980s and 1990s, namely a continuation of some traditional wine- making by default, but mostly a turn towards international grape varieties. This development must have been in part due to the fact that many new Greek wine- producers at the time were being trained as oenologists in France. But I have a feeling that Greek wine-producers thought that a turn to the internationally-recognized French grape varieties would propel them into the modern wine-making revolution that the rest of the world was already experiencing. It was modernity by imitation, attempting to copy the quality benchmark wines of Bordeaux, Burgundy (Chardonnays were also becoming widely available) and the Rhone Valley, much like the countries of the New World. A similar thing had happened to Greek pop music in the 1960s with the appearance of numerous bands essentially aping The Beatles, a conscious rejection of Greek folk music, which would have dominated the popular music scene in previous years. The results were charming, but have not aged as well. I now know that by the late 1980s, pioneer wine makers like Gerovasilleiou and Skouras, were already turning their attention to indigenous grape varieties, such as Malagousia and Agiorgitiko, alongside the Cabernets and the Chardonnays. However, their wines would take a few more years before they found their way onto most people’s dinner tables and into their basement cellars. I’m not saying I don’t like Greek wines made from international grape varieties. I do a lot. In fact, as quality continues to improve, the best of these wines are being exported, attracting the attention of international wine-lovers who until recently were only interested in the local varieties. But in the search for what might be the quintessential modern Greek wine, these bottles are not it.

Modernism is often defined as the rejection of tradition. Perhaps the most striking example of modernism is to be found in painting, with entirely new styles, techniques and themes evolving out of a more classical era, resulting in the works of the likes of Picasso and Matisse, that seem to be worlds apart from those of their predecessors. But a closer look reveals that modernism is not in fact the rejection of tradition: it is its transformation into something new. The 19th century painter Édouard Manet is credited by many as the artist who initiated modern art, and some of his most controversial works at the time, such as Olympia and Dejeuner sur l’herbe, were explicitly referencing and paying homage to classical works of art from the 16th century– Titian’s Venus of Urbino and Marcantonio Raimondi’s The Judgement of Paris, respectively. Manet’s paintings are clearly doing something different than those old classics: something that hadn’t been done beforeby introducing prostitutes as the subjects of his paintings instead of ancient goddesses, for example, or bringing his subjects into a new, more direct relationship with the viewer. But it is also clear that these paintings owe a lot to the classics they reference, and the newly developing criteria of success for these paintings only make sense in relation to those of the past. As the influential American art-critic Clement Greenberg writes “I cannot insist enough that Modernism has never meant anything like a break with the past. It may mean a devolution, an unraveling of anterior tradition, but it also means its continuation. Modernist art develops out of the past without a gap or break, and whenever it ends up, it will never stop being intelligible in terms of the continuity of art.”

One of the most celebrated modern Greek poets and Nobel Laureate Odysseas Elytis, also made a point of stressing that his task was to try and create something that could be recognized as a legitimate heir to the long tradition of Greek poetry that came before him, not merely to replace it by negating it. Elytis ended up making extensive use of the Greece’s poetic tradition in his work, incorporating themes and forms from ancient lyrical poetry, Byzantine hymns, as well as more recent folk music. At the same time Elytis was a modern, surrealist poet, influenced by the French surrealist movement of the early 20th century with which he had extensive contact during his years in Paris. His poems were at the forefront of modernism and quintessentially Greek at the same time.

Greek wine might be experiencing global recognition in the past 30 years or so, increasingly finding its way into wine menus of revered restaurants and on the shelves of prestigious wine retailers. Yet wine in Greece has been made for thousands of years, leaving behind a legacy of numerous grape varieties indigenous to the area. Greek wine modernism therefore could not simply be excellent Viogniers and Cabernet blends. It would have to be something within which this long tradition is detectable, but also transformed into something new. Santorini is possibly the first place that comes to mind as the area with the greatest wine tradition, going all the way back to Ancient Greek and Roman times. The Nemea region in the Peloponnese also has a distinguished wine history, and Agiorgitiko being a grape variety that according to myth gains its color from the blood that Hercules spilled when slaying the lion of Nemea. But Santorini is in a class of its own, perhaps due to its historic volcano eruption around 3,600 years ago, which defines the look of the island as well as its unique soil. The latter also protected Santorini from phylloxera, resulting in some of the oldest vine roots in the world, some with an age of hundreds of years. Assyrtiko from Santorini is also the grape variety that has had the most recognition around the world as the paradigm of modern Greek wine. The version of it that most critics seem to exalt is the stainless-steel-fermented, temperature-controlled versions of this wine, a style that was technically impossible only decades ago, producing a wine that is taut, mineral, clean, with great salty texture and with notes of lime and lemon. This is a delicious wine, one that rewards cellaring, after which the wine begins to develop honeyed aromas. But for me, Santorini Assyrtiko has a better modern interpretation: Nykteri, the name given to the dry(ish) white wine traditionally made in Santorini. It was mainly made from Assyrtiko, but also from other local indigenous varieties like Athiri and Aidani. The wine apparently took its name from the fact that the overripe grapes were picked and pressed at night (nykta). They were then fermented and aged in large, old oak barrels that weren’t topped up, resulting in a sherry-like oxidation. That, combined with the high alcohol and residual sugars left over due to the late harvest, resulted in a wine that little resembled the high acidity, steely, clean, mostly unoaked Assyrtikos of today. However, over the past few years a few producers in Santorini, starting with the late Haridimos Hatzidakis, started making Nykteri wines again. Despite keeping some of the traditional markers of this wine i.e. the late harvest and the fermentation and aging in old barrels, these wines are just off-dry and without the oxidative character of the traditional Nykteri. They are faultless wines, benefiting from contemporary clean wine-making practices, and more attuned to the tastes of today, with their acidity more prominent and their sweetness more restrained. However, they are still clearly identifiable as Nykteri: a round, rich, complex version of the Santorini Assyrtiko that can age for many years.

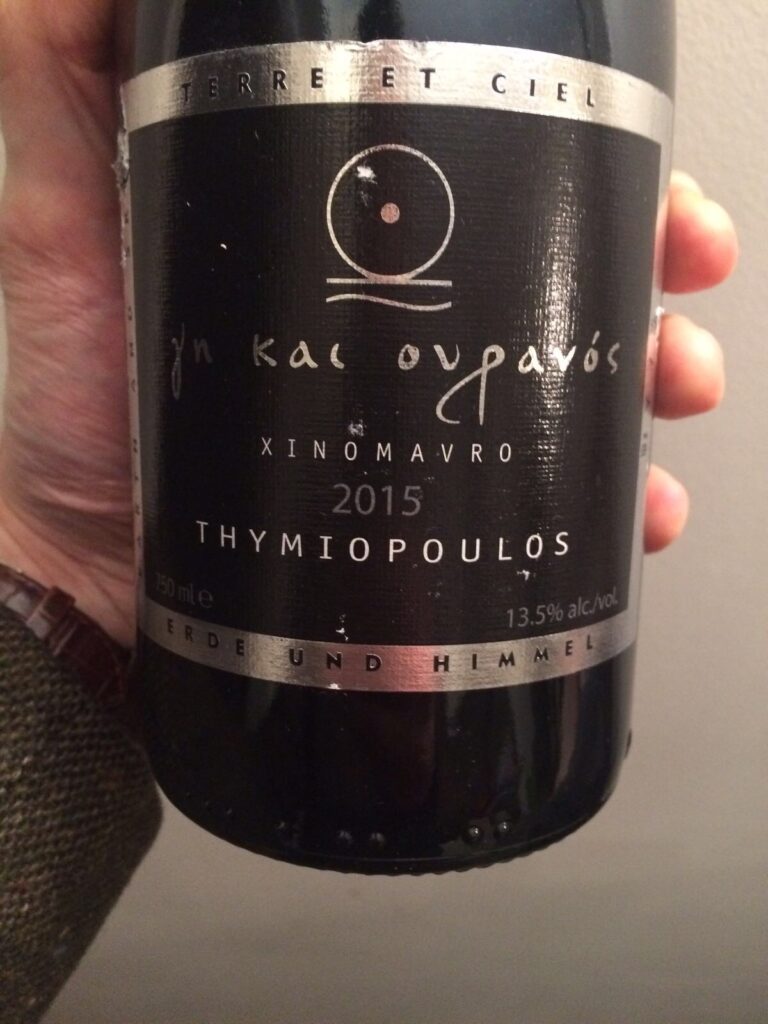

If Nykteri is the white wine representative of Greek wine modernism, new-wave Naoussa wine is the red-wine equivalent. Naoussa is a traditional wine region in the north of Greece producing predominantly red wines from the Xinomavro grape variety. One of the oldest wine families in Greece hails from this area, the Boutari family, with the homonymous company being founded in 1879. In 1997 one of the two brothers running the family business went on to found a new company, Kir-Yianni, and both are now big names on Greece’s wine map. Traditionally, Naoussa wines were rather rustic, exhibiting more of a vegetable than a fruity character, with tomato and olive notes, and with rather harsh tannins that needed some serious aging before they began to mellow. Despite this rustic character, Naoussa wines were appealing because of their great acidity and ability to age gracefully, developing some very complex earthy and mushroomy aromas, not unlike aged wines from Barolo and Barbaresco. However, over the past few years, a new generation of winemakers has been transforming the wines of the region into friendlier, more fruit-forward wines, with softer tannins that one does not have to wait a lifetime before they soften. There are now several wineries producing these new-wave Naoussas, but there is one undisputed leader of the movement: Apostolos Thymiopoulos. Thymiopoulos’ wines, interestingly enough, were first widely recognized abroad before they made a splash in the Greek market, and introduced the world to these elegant wines that some compare to Burgundy rather than Barolo, perhaps as recognition of their more fruit-driven aromatic profile, as well as their rounder structure. It’s hard to pin-point the secret behind these new wave Naoussa wines. When asked about it, Thymiopoulos likes to talk about the vineyard, rather than the wine-making process. He favours organic viticulture, sometimes stretching to biodynamic principles, though he is reluctant of calling his wines ‘natural’. His flagship wine, Earth and Sky, the full expression of modern Naoussa, has the power to age beautifully like the more-traditional wines from the area that can also be drunk young while displaying some crisp red fruit and fine tannins.

These two wines are for me exemplars of Greek wine modernism. They are the proof that modern Greek wine has come into its own, confident of its identity as a product of tradition interpreted anew.