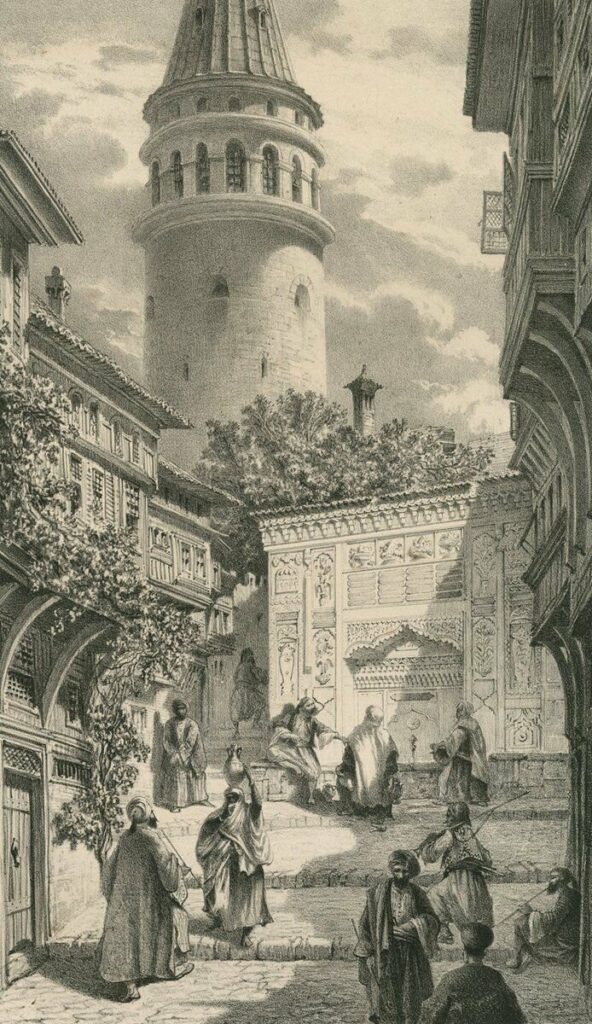

Before La Belle Époque was ushered in during the late 19th century, Istanbul was one of the most alluring “metropolitan” cities of the world. Situated at the western end of the Silk Road and buzzing with energy thanks to its diversified complexion, harboring a variety of cultures ranging from the Eurasian to the Mediterranean, being a port city bringing together two continents further added to Istanbul’s charm. Such dynamic splendor was bolstered, among other things, by a drinking culture that was built upon notions of camaradarie and jouissance. Drinking at the taverns lining up the streets of Galata, sailors, wanderers, men of letters, vagrants, singers, and all other sorts of Istanbulites recreated this city’s colorful harmony day after day… And, as brilliantly shown by the doyen Reșad Ekrem Koçu, the only way to unearth the real Istanbul is by attending to their stories…

From Constantinople to Istanbul

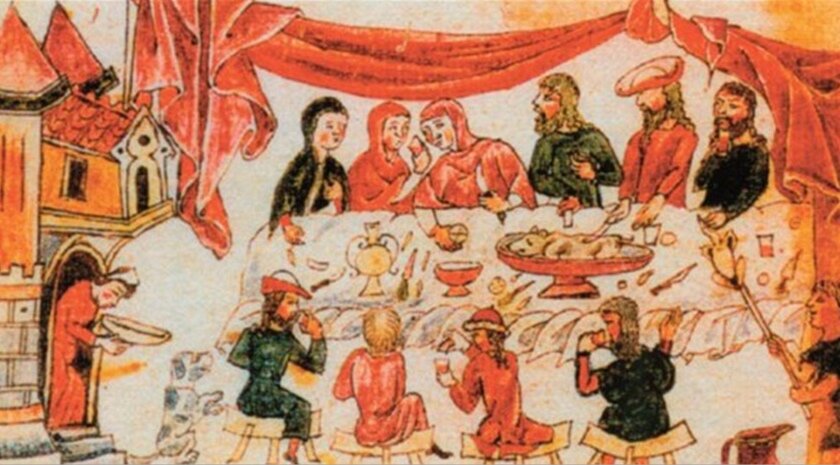

In Byzantion and later on in Constantinople, there were various establishments – some exclusive, some open to customers from all classes – that served alcohol, such as tavernia, pouskareia, and kapeleia. For instance, pouskareia, where pouska, an alcoholic beverage made from vinegar, water and beer, and favored by soldiers, was served alongside various legume dishes including fresh and dried chickpeas, lentils, and fava beans, were frequented predominantly by lower classes. Kapeleia, on the other hand, were licensed to sell wine alongside which they served various dishes made from meat, fish, and legumes, and might therefore be seen as ancestors of contemporary meyhane. Sula Bozis has even discovered the names of three such establishments that were located in the district of Perama (now, Eminönü): Melitrağos, Spanos, and Gorgoptulos. And, a poem, dating back to 5th century refers to a meyhane nearby the hippodrome and bathhouse, inviting bathers to enjoy a few drinks and a bite before the races in the afternoon.

In both Byzantine and Ottoman Empires, meyhanes were strictly regulated. In 895, Leo the Wise, famous for the various laws he issued during his reign, designated the meyhane (kapeleia) guild to be the sole authority in wine sales, thereby giving the guild the exclusive right to determine how, where, and at what cost wine would be sold.

The Byzantine central authority always kept a close eye on how meyhanes were run. Sometimes, it was meddling by men of cloth that brought about new and stricter regulations. For instance, there were periods when meyhanes were not allowed to set tables on the pavement, and men of cloth were prohibited from setting foot in them. Patriarch Athanasius (1289-1293, 1303-1309) not only demanded that meyhanes be closed during Lent (which could last for almost 6 months at the time), but that eating fish sold by women be banned at all times. In fact, already by the 9th century, meyhanes weren’t allowed to open their doors before 8 p.m. on Sundays (for religious reasons), and were forbidden to stay open after 8 p.m. during the rest of the week (for reasons of security, public morality, and to ensure revolutionary subjects wouldn’t have access to a space where they could sow the seeds of a potential rebellion).

Despite all this, by the 14th century, nowhere in Europe was wine consumption as key a component of daily life in the city as it was in Constantinople. (Eat, Drink and Be Merry – Food and Wine in Byzantium, Leslie Brubaker and Kallirroe Linardou (eds.)) As the Venetians and the Genoese took control of the wine trade in that same period, they received tax and tariff exemptions from the Byzantine Empire and also opened a number of meyhane in and around Galata and Eminönü, leading to official complaints by Byzantine meyhane owners.

The types of wine available in the city at the time included not only those brought from Aegean islands, Crete, and Ganos, but also locally produced, aromatized ones, whose recipes were inherited from the Roman Empire. Amongst the latter, the anise based “anisaton”, favored by doctors for its medicinal effects, is of special importance as it is deemed by many to be the ancestor of contemporary anise flavored drinks, including rakı.

Accounts written by travellers who were present during the conquest portray Istanbul as a city of meyhanes. As Resat Ekrem Koçu writes:

During the reign of Mehmed the Conqueror, Balıkpazarı (Eminönü) was already famous for its meyhanes. When the Turks took the city, they left the districts Balıkpazarı and Tahtakale, two densely populated areas where lower classes hung out in meyhanes and harabathanes (meyhanes that employed women dancers), untouched. We don’t know anything about their history prior to the conquest but there is no doubt that one of Mehmed the Conquerors’ close friends and an infamous drunkard, Poet Melihî, was often seen roaming the streets in the area.

Lâtifî Çelebi, a poet who lived in Istanbul in the 16th century, thought when it came to meyhane, Balıkpazarı and Tahtakale resembled Galata more than anywhere else. Like all other professions, meyhanes were part of a guild system. The guild president (Hamr Emini), a non-Muslim, was responsible for the sale of alcohol, issuing licenses to meyhanes, and closing down establishments that didn’t abide by the regulations. Besides the registered licensed meyhanes that were subject to the said regulations, there were also illegally operated establishments called quickies, where, as the name implies, you would have a quick one on your feet, and get going shortly afterwards.

The witty Ottoman explorer Evliya Çelebi provides the meyhane map of the 17th century Istanbul, and especially Galata. Evliya insists that as a devout Muslim he has never disobeyed any religious law, and yet, fortunately for us, he also doesn’t refrain from sharing his observations and knowledge about the city’s meyhanes. According to Evliya, who coined the phrase “Galata means meyhane” and his contemporary Eremya Çelebi Kömürciyan, there were roughly 200 meyhanes in 17th century Galata. The most popular among these were Mihaliki, Konstandi, Sarandi, Kefeli, Keskoval, and Sürmeli. Most of these establishments belonged to Chiosians, Moreans, and Anatolians, and were frequented by not only sailors from all around the world but also international pirates.

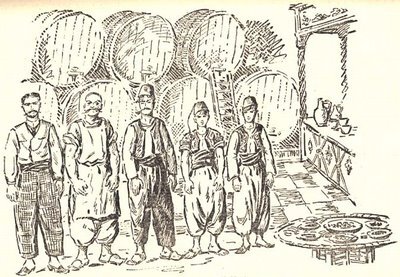

Some meyhanes were simply known as “factories” because they brewed their own Duziko (an anise based drink similar to rakı), liqueur, and cognac. As they kept these in barrels or clay jars, they were sometimes referred to as “barreled” or “jarred” meyhanes.

The first descriptions of inside the meyhane also date back to the 17th century. According to these, on a typical meyhane counter you would see wine glasses and carafe lined up, plates of bean salad with chopped onions and parsley, and dried chickpeas for customers who only wanted a quick one. However, the indispensible meze in every meyhane is the salted sardines, brought from Lesbos or Malta, and resting inside the huge barrel that sat at the foot of the central column.

17th century was also marked by a vicious cycle of banning and then legalizing the meyhane. As Koçu wrote:

Sultan Ahmet I prohibited the use of alcohol in July 1613, and also closed all meyhane and their guild. But, as a contemporary historian later on wrote, ‘As human nature is inclined towards depravity and evil, soon people were back to their drinking habits.

Similar policies ranging from ignoring alcohol consumption by Muslims to severely punishing it, from permitting only non-Muslims in meyhanes to banning them altogether and even burning down ships carrying wine were deployed during the reigns of Suleiman I, Ahmet I, Murat IV, and Selim III. But, as a general rule, these regulations were first relaxed, and then discarded entirely. What caused this vicious cycle? On the one hand, decision to ban meyhanes were taken as a result of pressure by religous officers, and the rulers’ security concerns and fear of rebellions. On the other hand though, alcohol tax contributed massively to the imperial budget and state officers were aware of the fact that banning meyhanes only meant alcohol would be consumed in shady, illegal establishments. And that is why, the aforementioned bans almost always ended up being relaxed, or discarded in a short span of time.

The only kind of meyhane that weren’t subject to prohibitions or bans was the mobile one, as they already operated outside the law. According to Reșat Ekrem Koçu,

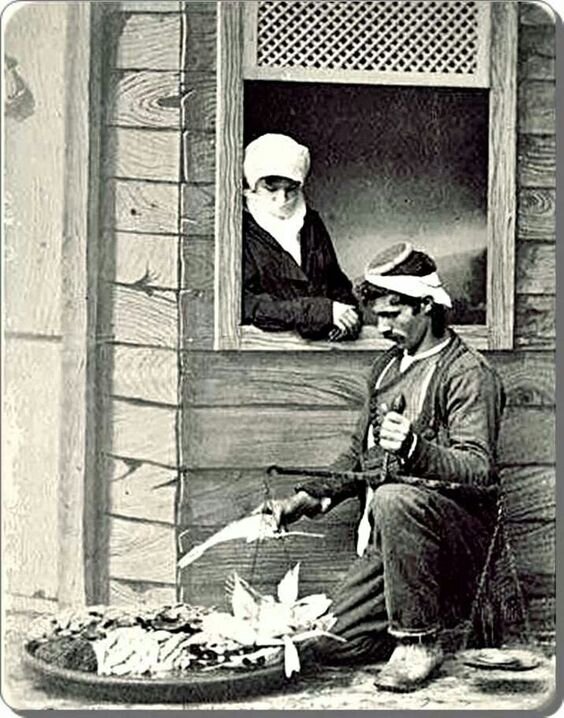

Members of lower classes, such as boatmen or porters, wouldn’t be allowed in licensed meyhanes, so they would either go to the small, dirty quickies or mobile meyhanes. The latter would often be run by Armenians and the owner was literally the meyhane itself: he was the counter, the waiter, the master… Wrapped around his waist was sheep intestines filled with rakı. He would keep glasses in his gown’s pockets and would carefully place a hand towel on his shoulder indicating that he was running a mobile meyhane. Once he saw a regular approaching, he would make his way inside a grocery store nearby and fill one of his glasses with the rakı that had been turned to yellow by his body temperature. The customer would pick up a bite of anything he found in the store – a leaf of cabbage, a piece of grape, a slice of radish, or as often happened, they wouldn’t have anything to eat with it at all. According to Evliya Çelebi, there were around 800 mobile meyhanes operating in Istanbul.

During the reign of Mahmut II (1808-1839) and later on Tanzimat (1839-1876), not only was alcohol consumption tolerated by authorities, but for the first time in the history of the empire, the elite started to appreciate rather than shame drinking in public. In the meantime, the authorities relaxed the regulations on running a meyhane so much so that some foreigners were able to open them near mosques. These punch-selling, English meyhanes became so common that local owners at one point filed an official complaint to the office of the Grand Vizier. And, according to an article published in Prodos in 1910, the Rum residents of Samatya asked the authorities to amend the law that did not allow any meyhane within 40 steps of mosques to include churches as well.

In his study on official registers dating back from 1850, Ahmet Cihan has found 115 meyhanes operating in 10 districts excluding Galata and the Golden Horn. (We can safely assume that there were more meyhanes in Galata alone.) Most of these were located in Ortaköy, Çengelköy, Üsküdar, Samatya-Yedikule, and Kuzguncuk. On average, every meyhane employed 2-3 people, and of all these employees, 83% were from Istanbul and only 2% came from Aegean Islands. This confirms our belief that the Rum mostly worked in Galata meyhanes, while the “local population” worked in other boroughs. Like their colleagues in Galata, the owners of these meyhanes (barba) hired young, handsome men. And, although owners and foremen were predominantly non-Muslims, Muslims could also work in these establishments, albeit at lower positions. Meanwhile, as we see in Keçecizade İzzet Molla’s Mihnet-i Keșan, military officers, bureaucrats, and scholars had already made a habit of having a fun evening out at meyhanes (or gathering at large villas where alcohol was consumed quite freely). Furthermore, we also know that scholars living in peripheral cities would frequently visit Istanbul, and after changing out of their “uniforms” (which included the turban) spend time in meyhanes and other drinking establishments.

Parallel to the developments in the second half of the 19th century, meyhane culture also went through a transformation and examples of what is today called a “classical meyhane” sprang up all around the city. In these grand meyhanes (which replaced the licensed meyhane of the past) rakı would eventually dethrone wine; although, at that point, there were various types of rakı in the market, duziko, more commonly known as duz, made without resin, was clearly the consumers’ favorite. Also at that point, Turkish bureaucratic elite began to see rakı as something that defined their distinct identity so much so that, after the population exchange with Greece in 1924, wine consumption in the republic dropped drastically, especially in relation to rakı.

Port Cities, Fish, Meyhane

It is time to reiterate what we hinted at, at the very beginning: meyhane culture is concurrently the culture of port cities. As a result of the high volume of marine traffic along trade routes, wealthy people who had ample amounts time at their hands (at least until they set sail again) would arrive in port cities, and in the case of Istanbul, frequent meyhanes. Different languages, colors, melodies, and tastes would thereby come together in Istanbul and some of the most delicious meals in the Mediterranean would accompany this amazing camaraderie that existed in meyhanes. Fish, the abundance of which caused the first residents of the city to settle there and which later became a Byzantian symbol, was of course always at the top of the culinary world of meyhanes. However, alongside it you would find fresh and pickled vegetables locally produced in the fertile greens of the city, and giblets from meat loaded on to ships (as they wouldn’t last the long journey and go bad). And so came into being tastes that would remain in the hearts and minds of meyhane lovers for years and years to come…

However, fish indeed occupies a very special place in the history and culture of Istanbul meyhanes. Even authors, explorers, and naturalists couldn’t ignore this “blessing” that halted the advance of Alexander’s ships one day, and changed the colors of the sea on another. The first person to mention the abundance of fish in the Bosporus was Homer in the 8th century B.C. And, almost a millennium later, Roman naturalist author Plinius couldn’t hide his amazement at the “branchial darkness” that descended on the Golden Horn:

Near Kalkhedon (now, Kadıköy), there is a magnificent, glittering, white rock that springs up from the bottom of the sea. When a school of bonitos come across it, they are so frightened by its dazzling sparkle that, they turn around and swim towards the Byzantian Peninsula. And, that is why it is called the Golden Horn…

In Taste of Istanbul’s chapter dedicated to fish, Sula Bozis quotes Pierre Gyllus who had visited Istanbul in mid-16th century. The visitor’s observations are a testimony to the abundance of fish in the capital:

…Venice, Marseilles, and Taranto are famous for their rich variety of fish but Istanbul is in a league of its own. The Bosporus is teeming with fish coming from two separate seas. At any point in time, there are such mass quantities of it swimming in these shores that residents can catch them with their bare hands. In the spring, people hunt schools of them swimming towards the Black Sea by hurling stones at them. And women living in houses on the shore simply dip baskets into the water, which are filled to the brim with fish when taken out.

Some believed that Muslims living in the empire had no interest in fish. For instance, Tuğrul Şavkay quotes a Spanish slave who succeeded in securing a post in the palace during the reign of Suleiman the Lawgiver: “Turks despise fish. Because they prefer water over wine, they fear the fish will come back to life in their stomach…” And yet, things are different in the meyhane. Once the locals start drinking, they start believing that it is not the fish they have just consumed, but their own being that has burst into life. How do we know they feel that way? From yet another explorer, Edmondo de Amicis, who visited Istanbul in 1874: “If one day, clouds of darkness descended over Istanbul and after one hour the sun rose again, 50,000 Turks would be caught with bottles of wine in their hands…”

As time passed by, fish came to be seen by all Istanbulites (and not only non-Muslims) not merely as a nutritious food item, but as an indispensible part of the camaraderie that existed in the meyhane. And meyhanes, which, alongside coffeehouses were the only spaces where a form of collective spectacle existed, kept its place in the hearts of Istanbulites, albeit with some breaks along the way.

The Neighbor’s Legacy

It is difficult to write a short history especially when we are dealing with the “age of extremes”. Unfortunately, during the last century of the 2,000 year-long history of this magnificently cosmopolitan city, we witnessed a depressing cultural desolation. The city that had been a host to two empires over the last two millennia met with the nation-state during the first half of the 20th century. City’s culture and ideology, and thereby its architecture, size, migration, consumption, and residence patterns went through a drastic transformation. Of all those changes though the most traumatic one was the transformation of the multicultural complexion of the city. Following the foundation of the republic there was an exodus of the oldest residents of the city, the Rum. In 1923, their population was halved from 300,000 to 150,000. Subsequently the formation of labor battalions, the institutionalization of Twenty Classes conscription system, establishment of Capital Tax, and the Istanbul Pogroms of 6-7 September 1955 further decreased the number to 90,000. Finally, the Cyprus issue which caused two separate crises in 1964 and 1974 resulted in the number of Rum living in Istanbul dropping down to a mere 3,000…

This is how the masters of meyhane disappeared from Istanbul. They were replaced by Muslims who worked in these establishments, who learnt the delicacies of running a meyhane from the barbas themselves. Naturally, meyhanes were transformed in accordance with the shifting consumption patterns and changing urban identity, slowly evolving into today’s meyhane. The quickies, fishermen’s, artisans’, and local meyhanes were replaced by “giant” meyhanes (which evolved from licensed and grand meyhanes), bars, fish restaurants, and kebap houses. Himself a meyhane owner from the Princess Islands, Fıstık Ahmet Tanrıverdi still remembers the days he lived alongside his Rum neighbors with fondness. His words reveal how the recent history of Istanbul is marked by utter sorrow: “It is so painful. Forcing the Rum population out of Istanbul is like extracting a perfectly healthy tooth.” When we visited Athens, the destination point for many of the Rum involved in the population exchange, we were surprised to see that there were less than a handful meyhanes run by ex-Istanbulites. According to researcher Sula Bozis, many of them simply no longer wanted to run a meyhane. However, there are also some establishments opened by people who worked in other sectors when they were in Istanbul, but decided to find a place for “food from their home” on Greek tables and became owners of successful meyhanes.

What remains of Athens is the story of Pavlis Moshakis, a painter whose work was exhibited alongside Fikret Otyam’s in the 1990s and an eternal habitué of Istanbul meyhanes. (Brother) Pavli, 100 years old and living in a nursing home today, has used the canvas to keep memories of his beloved Istanbul meyhanes and of his hometown, which he was forced to abandon, alive… Of course, always with a glass of Yeni Rakı by his side. It is his paintings that introduce us to meyhanes that left an imprint on Istanbul before the 1960s, such as Mina’s in Büyükdere, Cumhuriyet in the Fish Market in Beyoğlu, Passage Crespin, and those in Akıntıburnu.

The Transformation of Istanbul…

The tragic “desolation” mentioned above is not the only transformation Istanbul went through in the 20th century: as the city’s fundamental arteries were traumatically reorganized, Istanbul’s famous agoras were left in a state of atrophy. Initiated in 1950s, the urban renewal projects gained momentum in 1980s and after the turn of the millennia, transformed the city into a market good. That such a transformation would have a huge impact on Istanbul’s complexion was beyond doubt: the construction of Eminönü Square and the coastal road, destructions in Tophane, and renewal projects undertaken in Topkapı, Harbiye, and Tarlabaşı destroyed centuries-old boroughs, swallowed up historical agoras, and confined old meyhanes and their habitués to history.

Sociologist Tuna Kuyucu summarizes how such a transformation destroys the soul of a city:

As Jane Jacobs mentions in the The Life and Death of Great American Cities, ‘The aim here is to divide the city into functional zones and turn it into a fully planned space kept under surveillance at all times. This is the end of the city. A city has to flexible; it should be allowed to grow, change, and develop organically.’ The natural result of these renewal projects is the emergence of strictly regulated, exclusionary, authoritarian spaces… People who once resided in or visited these places cannot do so any longer. They don’t feel comfortable. Even if they are not formally excluded, they simply don’t feel comfortable. This discomfort, alongside a lack of financial means, means they don’t have many urban spaces they can frequent.

As a result, people end up living in a city that doesn’t allow spontaneity, confined to spaces that are secured (either privately or by police) and that are under constant surveillance like plazas, shopping malls, and public housing. The result of that: an entertainment sense characterized by its uniformity and confinement to specific spaces.

The old Istanbul was different: Even outside Galata and Pera, there were meyhanes all around the Marmara Sea coastline, Bosporus villages, and urban centers. In districts predominantly populated by non-Muslims the number of meyhanes was even higher. Mehmed Tevfik, a.k.a. Rookie, lists 83 of these in a 48-page booklet titled Meyhane or Istanbul’s Habitual Drinkers (circa 1880). Without a doubt, as Reșad Ekrem Koçu would later show, this was only a partial list. Rookie’s interest was limited to inside and immediate surroundings of the city walls and Samatya topped the list with 11 meyhanes. Then came Balat with 9, the coastline outside Balatkapı with 7, and Topkapusu, Tekfursarayı, and Cibali with 5 meyhanes to their names. The meyhanes were characteristically named after their owners or types of the building they were housed in. At the very bottom of the list we come across the anonymous meyhanes of Bosporus. In his Habitual Drinkers; Notes from an ex-Habitual Drinker, Osman Cemal Kaygılı describes music halls, quickies, shed meyhanes, and beer halls of 1930s Istanbul alongside the stories of their habitués and workers. His work proves that the number of Muslims in meyhane business have increased drastically since the days of the Rookie.

The non-rigid and participatory character of Istanbul’s neighborhoods makes them an important element of meyhane culture. On the other hand, the transformation in districts that resisted the aforementioned urban change and kept their identities as neighborhoods have to do with the changes in the demographic structure of the city. For instance, although Bosporus villages such as Arnavutköy, Tarabya, and Çengelköy and boroughs such as Kurtuluş, Kumkapı, Samatya, Yeşilköy, Fener-Balat, and Galata still host meyhanes, their clientele no longer comprise of the residents of these neighborhoods as they have been integrated with by Istanbul’s nightlife. The transformation of various Bosporus villages, Kurtuluş (Tatavla), and Galata is indeed drastic. For instance, according to Terpndros Marinos’s research, in 1951 Çengelköy hosted 22 meyhanes and 2 music halls; today, there are only 4 fish restaurants in the neighborhood. Despite all this, there are still proper examples of meyhanes continuing to serve neighborhood residents in Samatya, Yeşilköy, Kadıköy, Beșiktaș, Kumkapı, and Pendik Sapanbağları.

Meyhanes, Past Masters, and Drinking Customs

We are actually talking about a culture that exists predominantly in the Mediterranean but also all around the globe. However, the meyhane with its tradition of serving rich food initially with wine, and then rakı, has always reflected an authentic drinking culture and set of customs that go along with it. Historically, these spaces that are specific to Istanbul, have character but aren’t pretentious and this modest nature is reflected by the fact that they would only employ a handful workers at a time. The titles reflecting the status of the employees in the meyhane that often accompanied their names (and nicknames) constitute a key part of this culture. Back to meyhane owner Fıstık Ahmet (Tanrıverdi):

Barba owns the place. He is mature, and knows how to enjoy life. He is like a bohemian character. He is a philosopher, and like a maestro, rubs everyone the right way. Mastori stands behind the counter and pours the drinks. Finally, there is the page. He used to be called pedimu, which meant ‘my child’, and they would serve the customers.

Traditionally, the barba not only christened the meyhane but created its identity as well. Late Ziya Yücedağ, a habitué from Kuzguncuk, illustrates the relationship between barba and the neighborhood meyhane beautifully:

Everybody knew each other. Those who were on their own would quickly be invited to sit a table and drink with others. Barba would keep a close eye on the tables and the meze. As soon as the customer would sit at a table, the waiter would serve small amounts of mezes of the day. Once the customer’s face started reddening barba would cut off the meze. If the reddening didn’t subside, he would cut off the rakı as well. If it was the customer’s first time at the meyhane, the barba would test him out. They were like doctors!

Not only did the barba establish and enforce the code of conduct at the meyhane, but he also passed it on to his employees and young habitué – either verbally or through his gaze. In this regard, the words of Master Lefter quoted by his protégé, Kadir Bozkurter, himself a meyhane owner, deserve to be hang on the walls of every meyhane: “Meyhane is like a touchstone; if you were 24 carats when you arrived, you should be 24 carats when you leave. It wouldn’t be becoming if you were reduced to 17 carats.” One cannot but admire the persistence of this spirit even when meyhane tradition has all but disappeared today.

It should be noted this camaraderie was between men. From antiquity to recent times, traditional meyhanes are exclusive to men. In modern times, women constitute the face of the new meyhane; as such, all aspects of meyhane from the washrooms to service, from the traditional lingo to atmosphere inside is upgraded. Author and habitué par excellence Aydın Boysan’s interpretation of this change focuses on the transformation of the space:

Women arrived on the scene once American bars and meyhane were meshed together. Once they arrived, we stopped calling these establishments meyhanes. They became bars, or alcohol serving restaurants.

There are some interesting stories from the time of men-only meyhanes. For instance, men would cover the bottom part of their glasses with lace handkerchiefs knitted by their wives to remind them that their beloved were waiting for them at home and that they shouldn’t be too long. Today, in modern meyhanes of Istanbul we come across women not only in groups with men, but on their own, enjoying the camaraderie the meyhane produces. Respecting the past is important, but so is knowing how much of it needs to change…

The Tastes

One of the reasons why so many people cherish Istanbul cuisine is the richness of mezes, and related to that of course, is the rakı table set at meyhanes. However, “meze” itself isn’t a very old concept at all. In 19th Century Ottoman Cuisine, Özge Samancı and Sharon Croxford argue, “There are no meze recipes in any of the cookbooks published in Ottoman Empire during the 19th century.” That is why, in their own work, they include “dishes that could be classified as meze” in a specific meze section. Their work and numerous other pieces written on the subject show us how mezes were standardized, became part of the aforementioned rakı tables, and today, are reproduced each and every day in kitchens all around the country. Moreover, this particular cuisine, which at its core represents multicultural character of this city, is a heritage of not only Istanbul’s history but also of old neighbors. For instance, some of the mezes that have endured the sands of time, like tarator, salted mackerel, and pickled Bluefin have all originated in the Byzantine era.

Meanwhile, muhammara is originally Syrian, and fava (mashed broad beans) is an Antakya dish that is Arabic in its origins. Brain and neck (made from sheep meat) is Rum whereas topik (made with chickpeas, onions, potatoes, and tahini) and Armenian bean salad are Armenian. Circassian chicken and Albanian liver dishes cannot even be said to belong to a specific group, despite the presence of national indicators in their names. In short, in the words of cook-author Takuhi Tovmasyan (whose grandfather owned a meyhane), these diverse dishes make up Istanbul cuisine, or put in a more cinematic language, they make up the Politiki Kouzina, and that polis is Istanbul.

One of the reasons why meze was able to survive despite proliferation of main courses in meyhane is its close (and, in fact universal) relationship with rakı. Researcher/author Erol Üyepazarcı describes this relationship so beautifully that you almost smell the anise between the lines:

I’d like to note that rakı is special. Alcoholic drinks are generally divided into three: Aperitifs, drinks that accompany meals, and digestive ones. Rakı doesn’t fit in any of these categories. For instance, wine is merely a companion to food. That is why, specific wines are said to go well with specific types of food. Rakı is different because it is fundamental. That is why, special dishes, I mean mezes, are prepared to accompany rakı. That is also why, meyhanes are distinctive spaces that have to make a name for their mezes. And, since the second half of the 19th century, the concept of meyhane has been identified with rakı/meze.

From a Ritual to Entertainment

What has historically been a part of daily life in the city has been transformed into a component of urban entertainment paradigm. This is not only true for Istanbul but for metropolises all around the world. However, in some Mediterranean cities (despite the drop in numbers, Istanbul is one of these cities), neighborhood meyhanes that bring together different ethnic groups, classes, and generations together (similar to coffeehouses in Istanbul) still exist. The current manager of the famous Despina Meyhane in Kurtuluş, Ercan Tekin, believes this to be one of the essential characteristics of a meyhane:

Businessmen, artists, students, and of course, shopkeepers. Even the unemployed and neighborhood toughies. This is what a meyhane is, what it is supposed to be. It is heterogeneous, a concept that brings different layers of society together. There are some establishments – let’s keep them anonymous – that are only frequented by businessmen or artists. They are, in essence, private clubs, not meyhanes. It is good for them to use the name ‘meyhane’ but I believe we need to keep the philosophy and respectability of the meyhane intact. An establishment that does not bring together people from all social strata is not a meyhane.

These words carry a lot of meaning in today’s Istanbul where the biggest problem residents face today is intolerance and aggression… The sad state of affairs people who don’t converse, share, and get together find themselves in.

If You Want to Live in a Beautiful World, Find Yourself a Beautiful Meyhane

Despite being more expensive than they have ever been before, thanks to the major changes they went through, meyhanes still attract a wide range of customers: the shopkeeper who has a few quick ones in his lunch break, those who come together every day at a particular time to enjoy rakı as they discuss poetry, literature, or politics, the state officer who relieves the day’s stress with a few glasses before dinner, and all those who want to forget life’s pains in the meyhane… Of course, all these new establishments have new habitués and new codes of conduct. Meanwhile, the habitués of old describe the past to those who are willing to listen. At a time when alcohol has become so expensive and its brother “fish” has all but disappeared, when (with the disappearance of barba) the relationship between the owner and customer has weakened beyond repair, and perhaps most importantly, when our sense of collectivity has fallen apart, the meyhanes of the past simply couldn’t exist… Spread all over the city, new meyhanes continue to entertain Istanbulites though. And they are not even confined to physical spaces; as the owner of Hatay Meyhane, Mehmet Ali Işık points out, wherever mey is, so is its hane… with all its pleasures, joys, and melancholy. (“Mey” means alcoholic drink, and “hane” means house in Turkish.)

Let us remember, once again, Orhan Veli’s unforgettable lines from the end of Hoşgör Köftecisi: “If you want to live in a beautiful world, find yourself a beautiful meyhane.”

Meze in Meyhane

When our subject is meyhane, we cannot avoid talking about the meze tray that brings us the most delicious examples of Istanbul cuisine. In Turkey, the rakı table is usually referred to as “çilingir” table. The word literally means locksmith, but this specific usage is believed to have originated from the word “çeşnigir”, the name given to the kitchen worker responsible for tasting food (like a quality controller) in Ottoman palaces. Likewise, meze’s Persian origin, “maze” means taste, flavor. Çilingir in this sense refers to a table full of different mezes, albeit in small portions.

The secret of spending a whole night of drinking rakı with such small portions of meze lies in the habitué’s code of conduct, brewed over hundreds of years. It is this code of conduct that literary maestro Ahmet Rasim refers to when he writes, “one bluefish cheek lasts a hundred sips of rakı”.

Until two to three decades ago, meyhanes would not serve such a wide range of mezes. In fact, every meyhane would be known for a few mezes they made out of fresh ingredients, and those would be served without even waiting for customers’ orders. The most common among these were dried cod salad, pickled Bluefin, mackerel, and stuffed mussels. Habitués meanwhile would bring a few slices of dried meat, kashkaval, or fruits and share those with their fellow drinkers.

Today, mezes are identified with meyhane but in those days, they would be prepared and eaten on a daily basis in various households in Istanbul. In fact, we can safely assume that fish and olive oil dishes (neither were favored by Muslims) made their way into meyhanes from Rum and Armenian kitchens in Istanbul. For instance, topik an Armenian dish for Lent as it has no meat and yet is very nutritious, slowly made its way to the meze tray in Ottoman Istanbul. We can add Armenian bean salad, Roman pickled Bluefin, Byzantine Bishop’s stew, Rum dried cod, and a variety of tarator dishes to the list of mezes that kept their places on the meyhane trays over the years.

Meze occupied an important role in the habitué-barba relationship that formed the basis of meyhane culture for centuries. In the past, on the last day of Ramadan, barbas would send habitués’ home (as the latter would have refrained from visiting the meyhane during the holy month) a plate of stuffed mussels or mackerels, called “Don’t You Forget About Me stuffings”.

Therefore, the meze tray not only represents the ethnic diversity of Istanbul and preserves the millennia-old Istanbul cuisine for future generations, but is also a delicacy that reminds us of the value of the meyhanes, whose numbers have been slowly but steadily in decline.

Music in Meyhane

There is no meyhane without music. However, as they primarily host conversing groups, the volume of music should never be loud. There has always been live music in meyhanes (either classical Turkish or Rum) and during these performances, customers kindly cease conversing and pay full attention to the artists.

According to memoirs written in the 19th century, during the period in which women were not allowed in meyhanes, young male dancers, called köçek in Turkish, would perform alongside musicians. It was quite common in that period to come across homoerotic folk songs praising köçeks – the most widespread among these was Enderunlu Fazıl’s Çenginame. Besides these, every fight and murder that took place in meyhanes would take on a mythical nature and sometimes be turned into songs. And often it was not professionals but poor street musicians who performed in meyhanes, singing ghazals, and playing a variety of instruments such as reed, violin, recorder, or clarion.

Even today, amateur habitués who are confident about their singing abilities are held in high esteem by meyhane regulars. For instance Mr. Yakup, owner of the famous Beyoğlu meyhane that carries his name, told us how the imam of the Fatih Mosque would sometimes sing 5-6 ghazals a night for his customers, and how opera singer Sönmez Can would enliven the night with a few arias from his repertoire.

Turgut Vidinli, who used to own a meyhane (which today is a classical Turkish music club) in Beșiktaș, also told us 80’s divas, such as Müzeyyen Senar, Hamiyet Yüceses, and Safiye Ayla would reserve the entire meyhane and enrapture the employees with their beautiful songs. Likewise, on Sundays, Kör Agop’s (a Kumkapı meyhane that has been around for more than half a century) upper floor would be reserved for musicians from Istanbul radio who would entertain themselves for hours at end.

Going back to the past, just like mezes, meyhane music also used to reflect the multicultural complexion of Istanbul. Irrespective of their origins – Turkish, Armenian, Rum, Jewish, or Roma – artists would perform contemporary songs, folk songs, ghazals, ballads, srytaki, kleftiko (both are Greek folk dances) and zeybek (a folk dance from the Aegean region), and play a wide variety of instruments from all cultures such as violin, kemençe (a three-stringed violin from the Black Sea region), bağlama (a Turkish folk music instrument with three strings), lute, clarion, and recorder.

An incident narrated by Mustafa Cemil in his memoirs reveal the nature of fin-de-siécle meyhanes especially with regards to music. His father Tamburi Cemil Bey wenr to a meyhane around Langa (now, Fatih) with a friend of his. The Rum musicians who have been making music with Chiosian lutes insisted he join them with his kemençe. What followed can only be described as euphoria:

One of the singers kissed his hands. Cemil Bey was really fond of them so he couldn’t resist their pleas any longer. After a short introduction, he started to improvise. Initially a Turkish tune, then a srytaki and with a nod from him all the Rum musicians joined in. Then a kleftiko, some more Turkish tunes, and a kalamatiano… The old meyhane was filled with lively Aegean tunes. As Cemil played his final note, everyone inside jumped to their feet, applauding the master, cheering him…

Another well-known composer of the time, Tatyos Effendi was a very close friend of one of the greatest storytellers (particularly of meyhanes) of the period, Ahmet Rasim. One night, the two enjoyed themselves at a meyhane so much that Rasim arrived home very late. His wife gave him an earful and inspired by what he had heard from her, he wrote a song, for which, his partner in crime, Tatyos Effendi composed a beautiful melody. And this is how, one of the most popular meyhane songs of all times, “Don’t be Late, Come Early” was born.

Hand organs appeared in Istanbul meyhanes at the turn of the 20th century, and immediately became very popular. It was only in 1940s, with the introduction of gramophones that we saw the hand organs disappear from sight. Later on radio displaced the gramophone, only to be dethroned by the cassette player. Today, the only tunes in a meyhane come from mp3 files or mobile Roma musicians.

As we finish, we would like to fondly remember the magnificent accordionist of Cité de Péra, Madame Anahit and all other musicians who have adorned Istanbul meyhanes with their lovely tunes.

Note: This article was originally published in National Geographic Turkey in November, 2012. It is translated into English by Bora Isyar.

Lent : was and is a seven-week period of fasting / spiritual preparation for Easter and was not / nor is now six months.