The term “Nouvelle Cuisine” is not as new as one might think. Marin codified 18th-century French cuisine, while Menon (pseudonym) vulgarized it, but in return helped to create a broader base. Generations of cooks learned from no less than 200 years ago by studying the “Cuisinière Bourgeoise”, first published in 1746. Both chefs, Marin and Menon, created a founding legend of cooking styles with the catchy formula “Nouvelle Cuisine”, which subsequent generations of chefs would use to promote and market their own style. Throughout the centuries, cookbook authors have judged the “old cooking” of their direct predecessors as “gothic,” “complicated,” and “heavy.” Starting in the early 18th century there was a formula for success with which they generated interest:

(1) There is a nouvelle cuisine.

(2) This nouvelle cuisine is both art and science.

(3) It is lighter and more digestible than its predecessors.

Not infrequently, their protagonists are presented as inventors of at least one groundbreaking recipe. Their own equally scientific and artistic work is then praised by colleagues, teachers and critics.

The “Guide Michelin”, it was said, is the “Old Testament”, the Guide Gault-Millau the new.

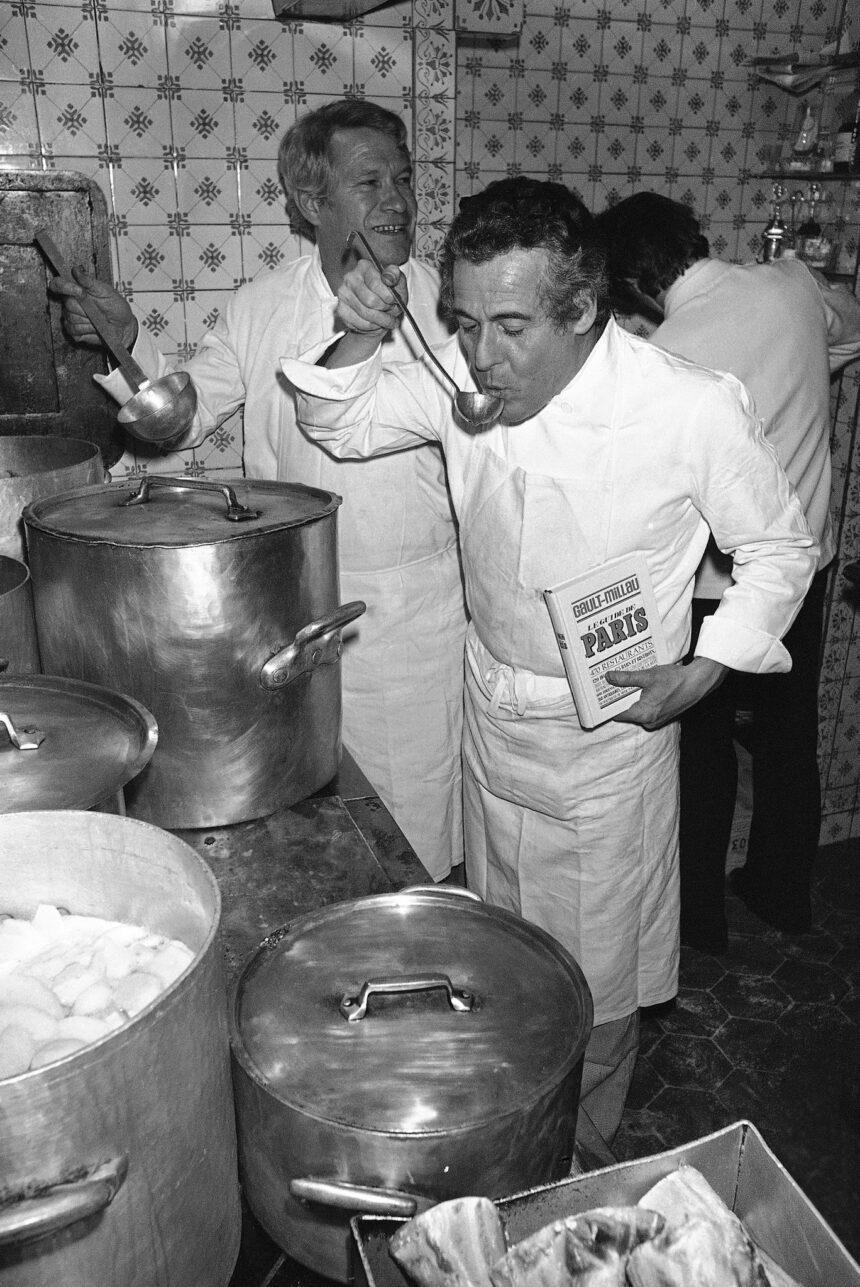

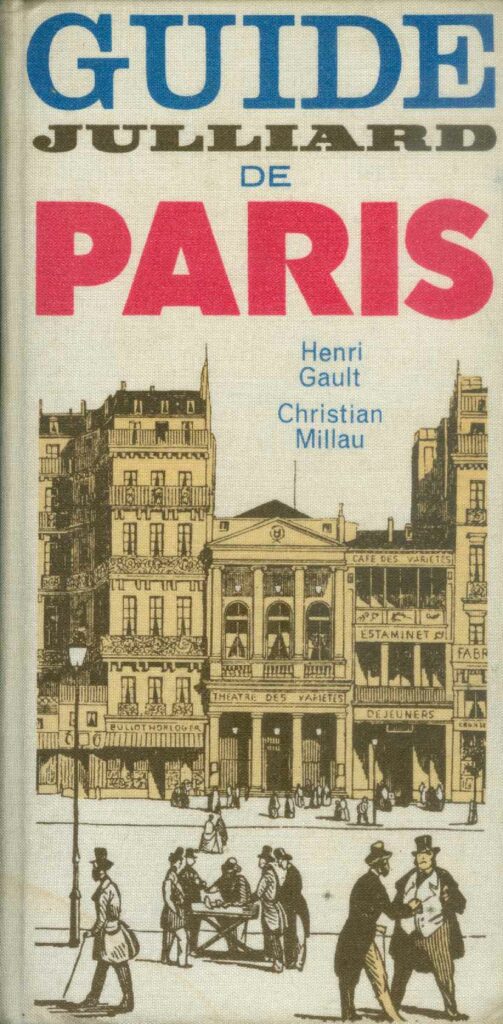

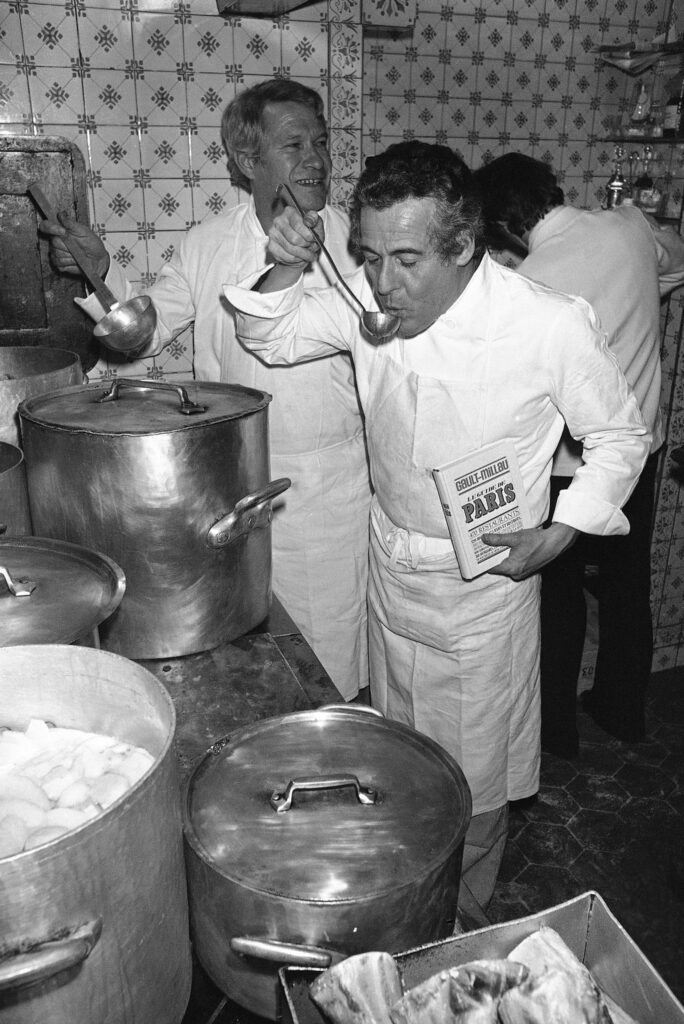

Regarding the modern-day Nouvelle Cuisine Francaise, Michel Guérard most typified the movement, considered as the “most nouvelle” among the chefs of the movement. But the concept itself came from the journalists Henri Gault and Christian Millau. The two colleagues from Paris-Presse had first made themselves a name in 1964 with their text for the “Guide Julliard de Paris”, named after the its publisher, which also produced the novels of Françoise Sagan. Their restaurant guide was fresh, eloquent, rated chefs like French students with marks between 0 and 20 and did not refrain from writing some tough criticism. No longer did chefs “cook as the bird sings”. Rather the guide did not shy away from scolding, puns and sometimes malice.

In the 1970 edition, they wrote about Restaurant Au Mouton de Panurge (“Panurge” used to describe someone who blindly follows other without regards of the consequences): “Ugly laughter, gossip and inimitable obscenities are part of our heritage. That’s why it’s important for your children to get to know this place.”

And about the Rotisserie Périgourdine: “We will never talk badly about this place again. This is the worst restaurant in Paris, this is the worst restaurant in Paris … This is the worst … This is … this is the best eatery in Paris, this is the best restaurant in Paris.” The restaurant received the rating 4/20.

The authors also did not eat very well at La Méditerranée in Paris’s Place de l’Odéon: “The carpets are still dirty, the fish in the fridge is forgotten, chocolate mousse is stuffed with corn starch.”

With their own guide came the success that catapulted Gault and Millau on the front pages of weekly newspapers, even in America. The “Guide Michelin”, it was said, is the “Old Testament”, the Guide Gault-Millau the new. Incidentally, this old culinary testament even claimed the life of a cook: Alain Zick of the Relais de Porquerolles on Rue Eperon in Paris. Zick had two stars and committed suicide following the loss of a star in 1966. His brother Rémy told the journalists of the “New Yorker” that loss of a star was the cause.

In 1973, Gault and Millau created another big hit. In their magazine, they published the “Ten Commandments of Nouvelle Cuisine”:

(1) Thou shalt not overcook.

(2) Thou shalt use fresh, quality products.

(3) Thou shalt lighten thy menu.

(4) Thou shalt not be systematically modernist.

(5) Thou shalt nevertheless seek out what the new techniques can bring you.

(6) Thou shalt avoid pickles, cured game meats, fermented foods, etc.

(7) Thou shalt eliminate rich sauces.

(8) Thou shalt not ignore dietetics.

(9) Thou shalt not doctor up thy presentations.

(10) Thou shalt be inventive.

Probably Nouvelle Cuisine was a tribute to the Nouvelle Vague of the French cinéastes of the 1950s. At least that’s what Paul Bocuse said. Some of the commandments were perceived like a menu by the chefs. You can choose a commandment, but there’s no need to have them all. #8-Dietetics? One dines in the restaurant to celebrate; lighter dishes can be achieved with smaller portions, which also saves money. #9-Do not doctor-up presentations? The sauce painters and sugar spinners who could still drape a chive stick heavenward falsified presentation twice a day. The commandment, #10-inventive (inventif in the original version, not créatif) became the excuse to declare each new dish a unique creation. And yet critics and chefs had once again taken the strategy of Menon and Marin to rise to the next level: There is a nouvelle cuisine; this new cooking is superior to the old–more creative, built on nutritional science and, thanks to the banning of adulteration, even more honest.

Light sauces, less-cooked vegetables, raw fish: “It has always existed,” Lahana recalled.

The teaching of Nouvelle Cuisine met an audience that never experienced “old cooking”. In France, the trente glorieuses (the thirty glorious years between 1945 and 1975) ruled with seemingly unrestrained economic growth: car ownership, the holiday in the South, the visits to top restaurants, everything seemed possible. The new clients got their restaurant tips from Gault and Millau who were two people the same age as the new clients, experienced in culinary delights and, especially in the case of Christian Millau, charismatic and eloquent. In addition, Nouvelle Cuisine had potent advocates. However, when Henri Gault and Christian Millau marketed their notion of Nouvelle Cuisine, the chef Denis Lahana had to step into the limelight as a representative of the older generation. In 1976, during a television program titled “Is there a New Cooking in France” (“Existe-t-il une Nouvelle Cuisine Française?”) aired on March 26, 1976, a showdown took place between critics and chefs. While the guests, including Paul Bocuse and pastry chef Gaston Lenôtre, were wondering what the new cooking might be like, the authors of the restaurant guide initially shied away from an answer. After some back and forth, they agreed on a reduction of the cooking times as one of the characteristics of the novelty. Then Denis Lahana said: “If you write that I was a difficult person because ten years ago I did not want to overcook fish, green beans, carrots, and wild ducks, and that this style is fashionable today, maybe I was ahead of my time.”

Light sauces, less-cooked vegetables, raw fish: “It has always existed,” Lahana recalled. The excesses denounced by Gault and Millau, including the seasoning of one and the same sauce with various herbs, never existed in grande cuisine, but only in bad restaurants.

Even Bocuse was attacked when Lahana explained that new cooking might also need new “hardware”. The Lyonnais Emperor of the Palate referred to the existence of the microwave. Lahana rolled his eyes and said he would wait for the new microwave-based cooking. Other celebrity chefs also refused Nouvelle Cuisine. Raymond Oliver (1909-1990), France’s then most prominent television chef, owner of the Restaurant Grand Véfour and author of the first multimedia cookbook “Cuisinorama” (with inlaid vinyl records), remained faithful to the tradition serving fish terrines, lamprey Bordelaise or pigeon Prince Rainier III. His most prominent disciple, Claude Deligne (1932-2013), who between 1971 and 1990 ruled the kitchen of the legendary Parisian restaurant Taillevent, did not shun the new cooking and liked serving the lighter sauces for his carefully modernized classic cuisine with dishes such as warm oysters on leeks, Cervelatwurst of seafood with pistachios or Poularde de Bresse. Both were successful as chefs, but hardly present in the media at the time of Nouvelle Cuisine.

But what was new about Nouvelle Cuisine?

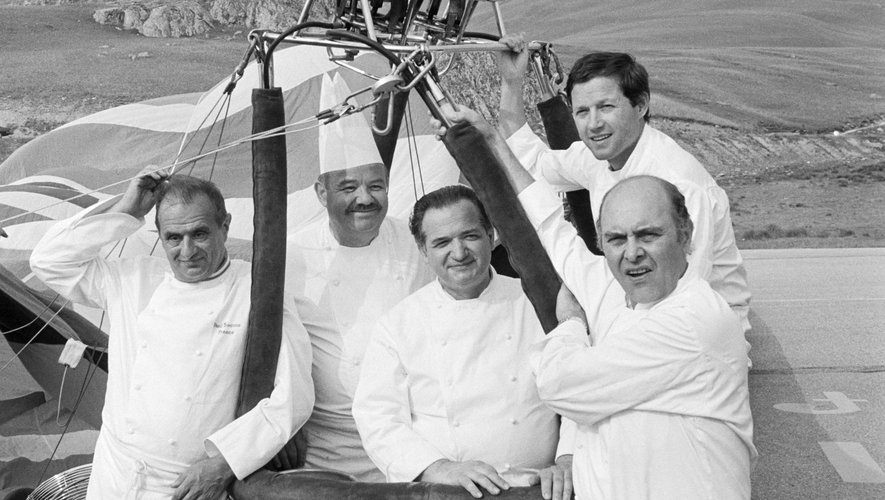

Was there really a new cooking in France? The only common feature of the chefs marketed as “new” was the temporary presence of salads made from al dente-cooked green beans with changing accompaniments on the menu such as foie gras or crispy fried sweetbreads. Otherwise everyone cooked their own style. Paul Bocuse, Alain Chapel, Pierre and Jean Troisgros, Louis Outhier, Jacques Pic, Paul Haeberlin, Roger Vergé, those were the names for all gourmets in the 1970s. These chefs were friends, but their cooking styles were profoundly different.

But what was new about Nouvelle Cuisine? The classic cuisine in the tradition of Escoffier has been taught in schools, but for decades it was practiced rather in grand hotels or particularly conservative restaurants such as the Tour d’Argent in Paris. The Merès de Lyon, Fernand Point and Alexandre Dumaine were successful with a comparatively simple, fresh cooking based on the best ingredients. Bocuse, the alleged figurehead of Nouvelle Cuisine, continued the traditional repertoire, as did Raymond Thuilier in his Oustau de Baumanière in Les-Baux-de-Provence. Alain Chapel, Jean and Pierre Troisgros, and Paul Haeberlin were committed to good ingredients. At Paul Haeberlin’s L’Auberge de L’Ill in Alsace, dishes such as lobster Prinz Waldimir, frog legs mousseline or partridge chop Romanoff were served, reminiscent of his teacher Edouard Weber, the personal cook of the Russian Tsar. Jacques Pic in Valence and Louis Outhier with a strong, on-going connection to his mentor Fernand Point, cooked quite conservatively in the 1970s in his Restaurant L’Oasis in La Napoule, outside of Cannes.

On the other hand, Nouvelle Cuisine simply sounded good in the ears of gourmets and restaurant critics, much like the Nouvelle Vague in the ears of artists and intellectuals. The message of the slender cooking also suited the lifestyle at the time. In 1966, William Bowerman wrote a book called “Jogging”. More or less simultaneously, Bowerman founded a company called Blue Ribbon Sports, or BRS, with his partner, Phil Knight, and $500 in seed capital. Only a few years later the company, which would most become associated with the fitness boom, became “Nike” after the Greek goddess of victory. Body fat, which was aggressively displayed in the devastation of the immediate post-war period, was in danger. For example, the very slender, androgynous British model Twiggy in hot pants graced the front pages of newspapers and fashion magazines. Excess pounds did not fit into the fashion of Swinging London. And then there were the young people in 1968 who, despite a steady economic upswing, went on the streets and somehow wanted everything: sexual freedom, breaking up with the old authoritative order typified by President De Gaulle, capitalism, the consumer society, the universities. The whole thing was underpinned by Utopian witty sayings like: “Be realistic, ask for the impossible”. All at once it was forbidden to forbid and it was said that the beach hid itself under the paving stones.

This new cooking fit in with a society that despised the old in the short term. However, the chefs involved are by no means in agreement as to whether Nouvelle Cuisine really had an effect on their dishes. Michel Guérard, again the most “nouvelle” of chefs and developer of the related low-calorie Cuisine Minceur, said in “La Libre Belgique”, that cooking had been trapped in the Escoffier system. “Our chef said in the morning, we make sole Joinville and everyone was fed up.” Guerard’s salad with green beans, asparagus tips, truffles and foie gras was then considered, because of some splashes of vinegar on the foie gras as a, “lese majesté”. The novelty of Nouvelle Cuisine was the commitment to lighter food and lighter sauces without sacrificing flavor. On the other hand, Edouard Nignon (1865-1934), the important early-20th century chef and cookbook author had already encouraged chefs to be creative, and even at the beginning of nouvelle cuisine, Michel Guérard himself served conservative, rustic fare such as fried tripe and sausage and his renown pot-au-feu.

For Bocuse, “Nouvelle Cuisine was never about food. It’s a story of post-war young people who got three stars.”

His father Marc would not have believed in Nouvelle Cuisine, reminisces Marc Haeberlin, but probably so in the “streamlining” of the recipes. Anne-Sophie Pic says her father Jacques was against Nouvelle Cuisine. He would have regarded it as a “loss of generosity” because of the tiny portions, which more than any other factor was done to make the meals more affordable. Finally, Louis Outhier was skeptical: “We looked at this thing. What does that mean, the Nouvelle Cuisine? Henri Gault decreed it one day “urbi et orbi.” Pierre Troisgros joked that he thought Gault and Millau were nuts when he read in their magazine in 1972 that he ran the best restaurant in the world. He subtly added that the two had created a “new journalism trumpeted with metaphors ” that ridiculed old gastronomic journalism.”

Several new words had slipped so into gastronomy, from the éclat (shard) to the copeaux (“chips”). The Troisgros brothers also played along, their salmon filet now called “escalope”, although until then the term was actually reserved for meat. Lobster became a navarin. The word was previously used for lamb ragout. Even Paul Bocuse contradicts the legend that Nouvelle Cuisine was a cooking revolution: he considered it a farce, and even Henri Gault had confided to him that he and Millau were salauds (“bastards”) because they led French cuisine astray.

For Bocuse, “Nouvelle Cuisine was never about food. It’s a story of post-war young people who got three stars.” The fact that haute cuisine was suddenly arranged by journalists instead of chefs did not appeal to him then and until he died: “The way things were going, we would not have been talking into microphones for much longer.“

Bocuse responded by creating an exclusive club called “Grande Cuisine Française“ with his friends the Troisgros brothers, Haeberlin, Outhier, Vergé, Pierre Laporte (Café de Paris, Biarritz), Rene Lasserre (Restaurant Lasserre, Paris) and Oliver. The chefs quickly received contracts from Air France and the caterer Servair. They were again in the foreground, the influence of the journalists was limited. Bocuse seemed a bit proud of that for decades to come.

The clientele was rejuvenated thanks to the economic upturn. “Half of the readers of Gault and Millau’s monthly magazine are in their 30s, of which 26 percent are executives and 20 percent skilled workers,” reported the German weekly “Der Spiegel” in 1974. Young people, who having had come into purchasing power, were exposed to revolutionary ideas in dining rooms where lobster dishes were named like lamb stew.

Due to the general enthusiasm for the Nouvelle Cuisine Française, more chefs became entrepreneurs. They were, as Chef André Guillot of Restaurant Le Vieux Marly in Marly-Le-Roi outside of Paris notes, naturally exposed to economic constraints. Austerity can be easily justified if you sell it as a great creation. In addition, the “new” chefs quickly developed a sense of self-promotion on all fronts: Bocuse already moved to French supermarkets with canned foods in the late 1970s, the ingenious Michel Guérard worked for Nestlé and filled cans with his dishes in his Comptoirs Gourmands. Wine bottles were adorned with the names of great chefs, as were jams and sauces. Their less-than-stellar quality was apt to challenge the role of the chefs as the gatekeepers of good taste.

The verbal justification for such culinary misdeeds was founded by Paul Bocuse: canned food is the prêt-à-porter of the great chefs. But where a reasonably talented tailor can at least adapt the length of sleeves and trousers with real prêt-à-porter, the taste remained permanently industrial at the culinary prêt-à-porter.

French chefs have always traveled the world, adapting their cuisine to local conditions. Carême was cooking with the Tsar. Many dishes by the German chef Franz Pfordte (1840-1917) were clearly inspired by the French. Henri Soulé’s Le Pavillon was the best-known French restaurant in New York from the 1940s to the 1960s.

“The dumbest chef,” Le Monde said, “now offers sea-bass with blackberries and leg of lamb with kiwis.”

Now Nouvelle Cuisine was the first cooking fashion to be marketed worldwide while taking full advantage of modern communication methods. Michel Guérard and Gault and Millau were on the cover of the USA edition of Time magazine. Bocuse’s image graced the covers of magazines worldwide, and he was often referred to as the “Chef of the Century”. Chefs in their high, white toques appeared on television screens worldwide. Nouvelle Cuisine brought the chefs into the limelight in an unprecedented way and sparked interest in fine dining far beyond France.

At the end of the 1970s and the beginning of the 1980s the saying “Nothing on the plate, everything on the bill” began to be heard. It was allegedly influenced by Paul Bocuse. French gourmets were annoyed, unlike German ones, by the fixation on visual effects practiced more by less-talented chefs. Nouvelle Cuisine was starting its decline.

A German article in “Der Spiegel” from 1979 stated: “Especially the vegetable purées, which are often beefed up with whipped cream, so that they are pretty frothy, are now criticized.“

“This is something for toothless old people,“ complained the editor-in-chief of the “Guide Kléber”. The Feuilleton of Figaro made reference to “baby food”. The gourmet salads, which are now being admired as an appetizer in Germany, are similarly discredited. There are truly disgusted Parisian critics who have to eat the weird blends that were put together in expensive restaurants. One of them had to eat rabbits with raspberries in a two-star restaurant. Another was served roast veal with honey and quails with apricots. “The dumbest chef,” Le Monde said, “now offers sea-bass with blackberries and leg of lamb with kiwis.”

Even Christian Millau declared in the mid-eighties that he no longer uses the words “Nouvelle Cuisine”. Word creations such as “Post-Nouvelle Cuisine” were also unable to prevail. The guests still wanted to taste lighter sauces, but the hype about the tiny portions and the graphically-designed plate constructions annoyed the clientele. The “Après Nouvelle Cuisine” that followed was characterized by buttery mashed potatoes, pig’s head Île-de-France and rack of lamb in salt crust. These were the dishes of Joël Robuchon.

This essay originally appeared in the book “Die Erfinder des Guten Geschmacks : Eine Kulturgeschichte der Köch”, Bastei Entertainment. Cologne, 2013 (“The Inventors of Good Taste: A Cultural History of the Chef”). After it was edited lightly in the translation to bring it up to date, we have published it in collaboration with Diningology.org.