Gastromondiale—its editors and contributors—comprise a diverse group of diners and critics who believe that gastronomy ought to be directed foremost to the unadulterated pleasure of eating and drinking. In contrast, today’s restaurant industry capitalizes on dishes that dazzle the eye but leave the palate numb; articulate complex ideas that translate poorly to the plate; advance a high-minded political agenda but abandon the quotidian duty to render the utmost to the diner who comes to the table.

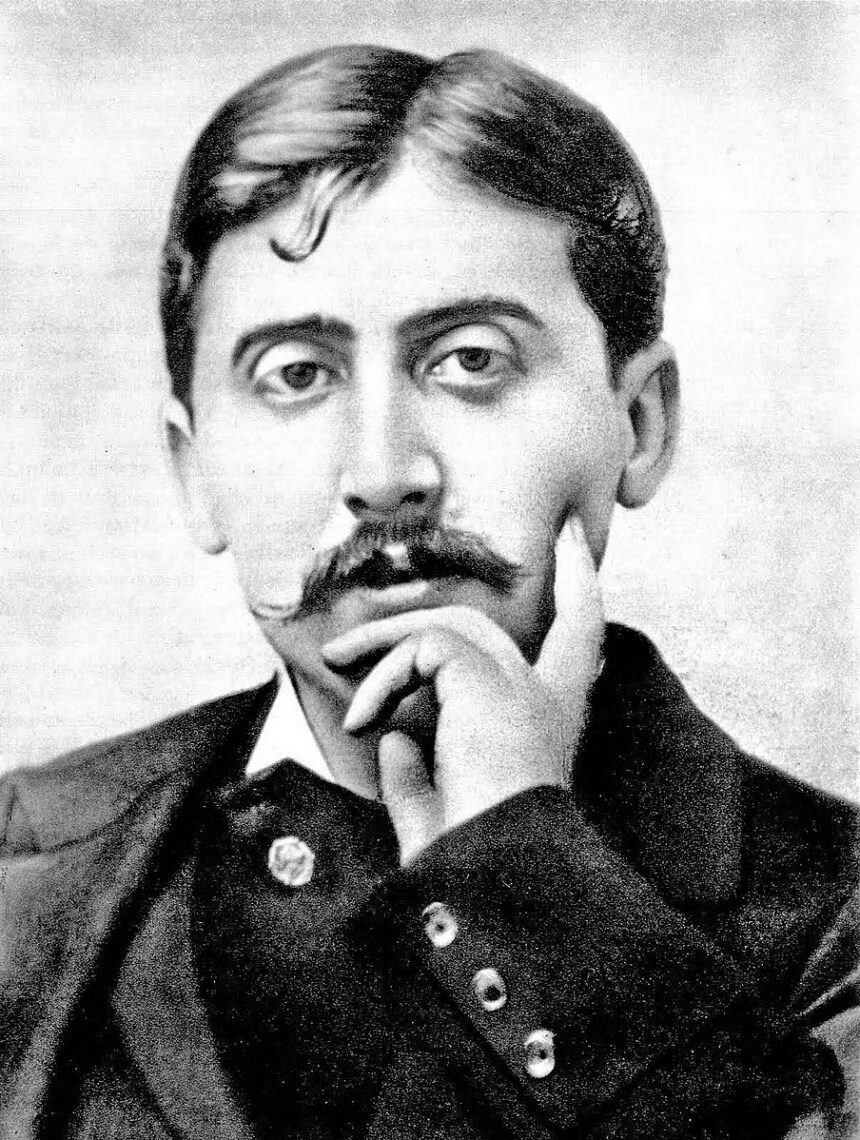

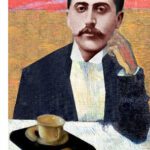

The hedonist stance of Gastromondiale is therefore less reactionary than resistant to the expedient aims of the market and its ideology. In this distrust of the marketplace of ideas, our stance has more than a single affinity with the popularizer of madeleines (for which he exhibited no outspoken affinity), Marcel Proust. In contrast to the naturalist authors of his epoch, Proust was skeptical that a literature which took recourse exclusively to sociology or biography, easy sensationalist tag lines, could access a truth that palpably insisted itself into one’s very being. The way Proust assessed the literature of ideas is akin to how we view the gastronomy of ideas: mildly interesting but hardly compelling. Proust sensed that the Intellect was important, indeed integral, but only when it is preceded by the physical sensation that disturbs us out of our complacency, forcing us to think.

At Gastromondiale, we are moved by dishes that entice our senses and only subsequently instigate us to consider the technical or semiotic dimensions of a dish. The organoleptic aspects may provoke comparisons. One tastes the rey fish at Güeyu Mar and the variegated textures also encountered in wagyu are superseded by a depth of flavor more profound than any beef. The historical relevance of a dish can equally follow suit. Alain Passard’s vegetable pasta transports the diner to an alternate history of Roma, where the spaghetti carbonara might have benefited from the minerality of potatoes. Suffice it to say, both dishes send one uncontrollably on a path of rumination. In their initial, visceral appeal, they resemble madeleines. It is in this spirit that we appropriate the Proustian icon to denote three privileged moments from the dining year 2017.

Vedat MILOR

Reyfish at Güeyu Mar

In a recent review, I claimed that the two restaurants in Northern Spain were the apotheosis of Western seafood. It is probable that their chefs, neither Abel of Güeyu Mar, nor Aitor of Elkano, perceive themselves as great chefs. However, they are equipped with powerful “a la parilla” (grilling) techniques. When these techniques are combined with the amazing quality of the line-caught fish, the cleanliness and cold temperature of the sea in Northern Spain, the depth of the sea and strong currents when the fish is caught, I really do not have any doubts that you cannot find this level fish in any Michelin three-star restaurant or in any of the so-called top 20 restaurants of the world (with the possible exception of Asador Etxebarri). When you have grilled reyfish in winter at Güeyu Mar you will see that calling it “the wagyu” of fish is not high praise. On the contrary as it is more complex and fulfilling than wagyu.

Spoonful of raw peas at Elkano

Basque people call it green caviar, but it took me time to fully grasp how good peas can get until Aitor brought in a spoon “guisantes” freshly picked from Juanito’s garden in San Prudencio, Getaria. The garden is next to txakoli vineyards by the seashore. Sweet and saline, mineral and soft despite being raw, this is a product that should be tasted from the right terroir upon picking. The constant ocean breeze that it receives from the ocean all year long gives it a very particular and distinctive briny taste. Its quality is dependent on how fresh it is and the size of the product, but Juanito’s organic farming must also be an important factor in making these peas as rare as wild beluga caviar and, as good!

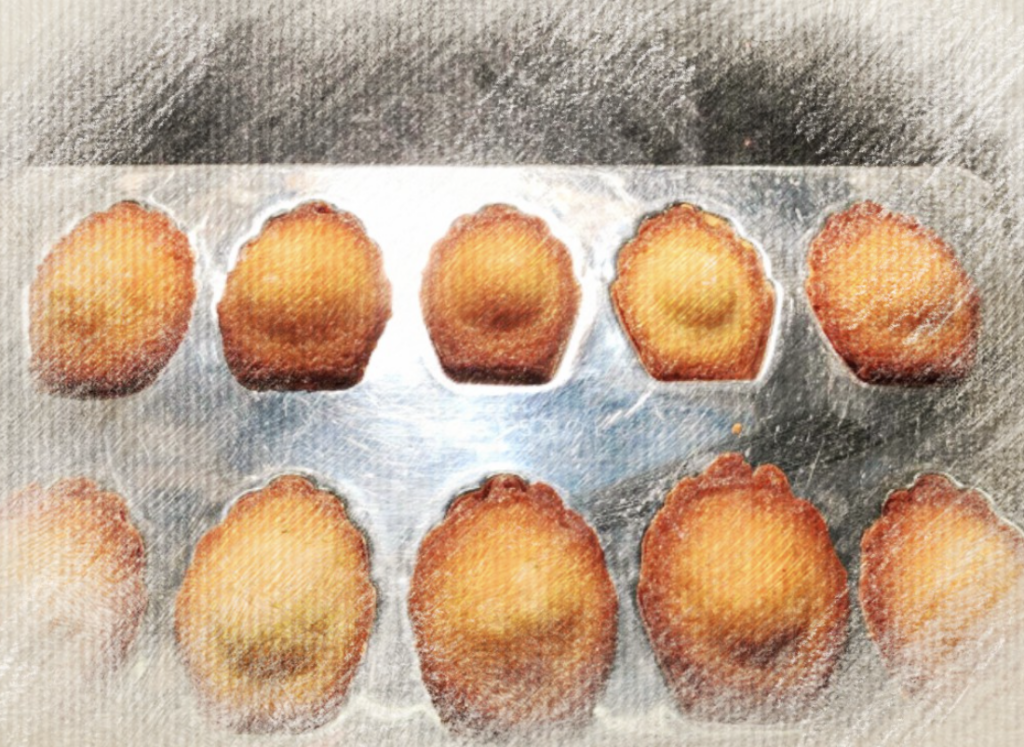

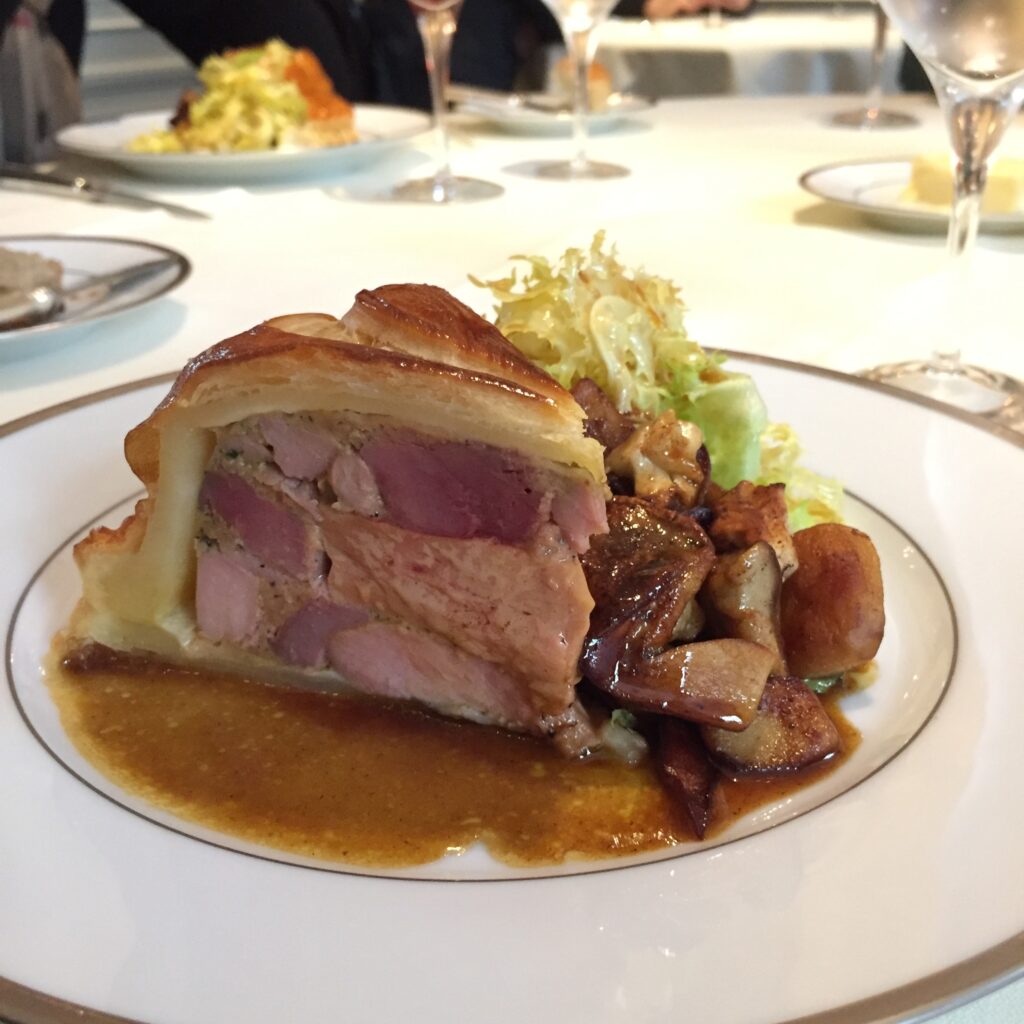

Tourte de canard at L’Ambroisie

Bernard Pacaud deserves a lifetime achievement award for this masterpiece or “plat d’anthologie”. It is not only the flavor but that the balance of the main components are exceptional. I would not have understood the historical significance of this dish had Atahan Tuzel not brought to my attention its decline during the sad period when the son Matthieu was running the kitchen. The big difference is what Atahan calls father Pacaud’s “tour demain/geste/delicatesse”. You have pieces of duck breast, veal and pork and a lobe of foie gras encased in a puff pastry and a fine farce of duck neck and other parts. There are several amazing things about this dish: First, different parts of the meat are cooked to perfection, retain their texture, and are held loosely together as opposed to being packed together. Second, the foie gras lobe is like the crown jewel, and Pacaud has retained its silky texture. This blends perfectly well with other pieces. Third, the fine farce is a work of art and a craftsmanship that is now lost rolled into one. It is not the pate en croute of many pithiviers prepared by using a blender. I do not know how Pacaud makes it, but you see some pores in it, as opposed to a whole lump of meat. The fine farce is delicately placed to surround the pieces of meat so that it adds more than complexity; it absorbs the steam of meat cooked in the pastry. Fourth, there is the puff pastry. Itself. It is not a feuillité like another legendary Pacaud dish, truffe bel humeur. Thus, it is not flaky, crisp, or soggy. It is very thin-like three-fifths of an inch, and it is certainly hard to work with, an interesting point that Atahan brought to my attention: Look at the proportion between the relief (the thicker part of the dough, which helps to cook it) and the flat part of the dough. Pacaud minimizes the thicker part to achieve absolute harmony and the best cooking of the meat and foie gras. During his son’s reign this proportion had changed in favor of the relief, which made cooking easier but made the duck over-cooked. It is quite incredible how “airy” and well-cooked the thin dough is without being soggy. Last, the bottom of the pie is not soggy as the jus is used very judiciously. The sauce adds complexity to the dish by flavoring the frisée salad and pico magnatum (Alba white truffles) served alongside. Overall this dish brought tears to my eyes.

Robert BROWN

Most dishes these days going whizzing past while relatively few stop and chat. Those that speak to me hang around and become like new friends. You spend an appreciable amount of time sizing them up and getting to know them. When you are finished with the encounter, the truly great ones stay in your mind, and you hope to meet up with them again. That this is occurring with less frequency these days results in experiencing overall, often vague, impressions of meals rather than vivid memories of discreet dishes from a place remembered. This phenomenon is why two of my three preferred dishes of this past year were with old friends first encountered a decade or more ago, and the third one a hearty, traditional and end-of-year seasonal dish of impeccable execution that exists in various versions in Northern Italy.

For the first time that I can recall, I went through a year without setting foot in a tasting-menu-only restaurant unless you include in in this category kaiseki restaurants meals in the foodie’s Mecca, Japan, of which I had many during cherry blossom season. Whether or not you view such restaurants as dégustation restaurants, which I do not for reasons I won’t elaborate here, the dishes still went whizzing by. Some I still can recall some with fondness, my favorite being rice with turtle eggs that came, as tradition calls for, at the end of the savory part of my meal at Kasumicho Suetomi in Tokyo.

Tomato gazpacho with mustard and celery ice cream at L’Arpège

I have been a partisan of Alain Passard’s L’Arpège since he started the restaurant in 1986 in the former quarters of Alain Senderens’ restaurant L’Archestrate. I have spread my visits out rather evenly since then, and it appears to me that after three decades, Passard’s cuisine hasn’t lost a beat or shown signs of a loss of creative energy. His tomato gazpacho with mustard and celery ice cream is emblematic of how Passard engages in the culinary equivalent of a free-range brain that puts together two seemingly-diverse, unrelated concepts into an engaging, unexpected insight that rings true, something that only very few chefs can do. The flavors are assertive and pronounced with a refreshing encounter of cool and cold. I like how the celery flavor counteracts the acidity of tomatoes and mustard.

There is no law saying that you have to enjoy or appreciate a dish more because it has some extra-culinary quality. However, as I consider myself something of a dining romantic, I further enjoy dishes that have the added dimension of a history. It is not enough to eat a bistro dish such as coq au vin or blanquette de veau. Rather, it must have something like attachment to a place, an event, or a person; examples being a Pithiviers (an en croute dish named for the town 60 miles due south of Paris); L’Oreillier de la Belle Aurore (another en croute creation created by Brillat-Savarin circa 1800; and the Gateau de Foie Blond Lucien Tendret, named after the 19th-century lawyer and gastronome who was Brillat Savarin’s grand-nephew, and a dish given a renaissance throughout the history of Restaurant Alain Chapel.

Finanziera at Antica Corona Reale di Renzo

Piemonte’s entry in the gastronomic history canon is the finanziera, The facts around it are somewhat murky. One source says the dish dates from Medieval times, another from the 18th century when someone named it after the red jackets worn by the Turin tax officials who were offered the dish when they visited the humble people from whom they were trying to extract money. Regardless, what I like about the dish is that its ingredients are also humble, but that eating it imparts a feeling of luxury that is punctuated on the finish by Marsala wine and balsamic vinegar. As is often the case with creations that have withstood the test of time, no two versions are the same. The ingredients in the rendition at Ristorante Antica Corono Reale di Renzo, outside of Cuneo, are veal sweetbreads; veal veins, brains and strips; lamb kidneys and livers; rooster crests, spleens and hearts; lamb livers; caul fat, Bra sausage; celery; carrots; onions; balsamic vinegar; white wine; and Marsala wine. Its various entrails are breaded and fried.

The finanziera at Antica Corona Reale has been the only restaurant where I have had it, the first and only other time at least ten years ago. Just as it’s a dream of mine to travel along the Adriatic coast to eat the various versions of the fish stew brodetto, now I feel an urge to hop around western Piemonte to indulge myself with this earthy, if not quirky, lynchpin of Piemontese cuisine.

There is no law saying that you have to enjoy or appreciate a dish more because it has some extra-culinary quality. However, as I consider myself something of a dining romantic, I further enjoy dishes that have the added dimension of a history. It is not enough to eat a bistro dish such as coq au vin or blanquette de veau. Rather, it must have something like attachment to a place, an event, or a person; examples being a Pithiviers (an en croute dish named for the town 60 miles due south of Paris); L’Oreillier de la Belle Aurore (another en croute creation created by Brillat-Savarin circa 1800; and the Gateau de Foie Blond Lucien Tendret, named after the 19th-century lawyer and gastronome who was Brillat Savarin’s grand-nephew, and a dish given a renaissance throughout the history of Restaurant Alain Chapel.

Finanziera at Antica Corona Reale di Renzo

Piemonte’s entry in the gastronomic history canon is the finanziera, The facts around it are somewhat murky. One source says the dish dates from Medieval times, another from the 18th century when someone named it after the red jackets worn by the Turin tax officials who were offered the dish when they visited the humble people from whom they were trying to extract money. Regardless, what I like about the dish is that its ingredients are also humble, but that eating it imparts a feeling of luxury that is punctuated on the finish by Marsala wine and balsamic vinegar. As is often the case with creations that have withstood the test of time, no two versions are the same. The ingredients in the rendition at Ristorante Antica Corono Reale di Renzo, outside of Cuneo, are veal sweetbreads; veal veins, brains and strips; lamb kidneys and livers; rooster crests, spleens and hearts; lamb livers; caul fat, Bra sausage; celery; carrots; onions; balsamic vinegar; white wine; and Marsala wine. Its various entrails are breaded and fried.

The finanziera at Antica Corona Reale has been the only restaurant where I have had it, the first and only other time at least ten years ago. Just as it’s a dream of mine to travel along the Adriatic coast to eat the various versions of the fish stew brodetto, now I feel an urge to hop around western Piemonte to indulge myself with this earthy, if not quirky, lynchpin of Piemontese cuisine.

Roasted goose leg wth plum sauce at La Bitta

Another aspect of dining romanticism is serendipity or an encounter with a creation that hits you where and when you least expect it, invariably in a restaurant without a symbol or a number next to its name. I had two such dishes in 2017. The first was venison haggis in the Glasgow restaurant The Ubiquitous Chip (or U.B. Chip as the locals call it). I cannot recall the last time I had haggis. Perhaps I never had. Still, this dish, which is also based on offal, caught me completely off-guard with its vibrancy and succulence. I well could have awarded our madeleine to this dish. In the end, however, I opted instead for this:

Make no bones about it, eating in Venice is for seafood lovers, but on Mondays when the main fish market by the Rialto Bridge is closed, along with most of the better seafood restaurants, meat takes front and center. Relying on a very good and, as it turned out, quite reliable, list of recommendations by Anne Hanley in an eight-month-old Venice restaurant survey in the UK’s the Telegraph, we landed at La Bitta, one of the easier restaurant to find in the labyrinth known as Dorsoduro, a part of Venice where a GPS on your phone will get you more turned around than relying on your sense of direction.

La Bitta is a classic rendition of a simple, intimate bistro or trattoria—a bar on your right with a few tables as you enter and a small dining room in the back. The cuisine is rigorously classic and faultlessly prepared. We were delighted with the restaurant’s beef carpaccio and fegato alla Veneziana. What knocked us for a loop, however, was the roasted goose leg in prune sauce served with apple, prunes and tuiles of mashed potatoes. Its overwhelming rich and somewhat sweet taste was like a left hook coming from seemingly nowhere. After roasting, the chef braised the leg in the thick prune sauce that echoes the Mitteleuropa aspects of the local cuisine. We could have easily downed another portion, so tender and easy to eat was the one and only, despite not having arrived with a full appetite. The fact that the dish is not in the least photogenic tells you something about the correlation of “pretty” food photos and the qualities that matter most in a dish.

I was finally able to try the torte last November. Unfortunately, the top of the pastry was not in very good shape. The taste, however, was amazing.

I love the combination of something almost rustic executed in the highest manner.

That is a very lovely description of the various components. It will be helpful in appreciating the dish even more the next time.

I cannot find any information when searching for "reyfish". Is there another name for it? I am trying to find out when it is available at Gueyu Mar.

-Joe

Dear Joe,

El rey is served almost all year round, but the best times are between November and July. The summer is the worst time to have it.